Justice. The driving force of various historical movements seeking change. A topic discussed by philosophers past and present. An idea that has taken on many different forms, the latest of which is “social justice”.

Everyone wants justice. However, people can mean different things when they talk about justice.

A person advocating for justice and another advocating for social justice could be supporting completely different things. Even among supporters of social justice, definitions of the term vary.

JUSTICE: A MODERN INTERPRETATION

When people talk about social justice nowadays, they are usually referring to a specific version that is intertwined with critical theory (that is also the version I will be discussing).

Critical theory itself is a complicated worldview. While it is impossible to summarise critical theory into a single article, here are three core premises I have observed.

The CSJ movement is about the elimination of all forms of oppression, where “oppression” is defined by critical theory.

The first premise is that individual identity is inseparable from group identity. Who you are as a person depends on the social groups you belong to based on identity markers like race, sex and so on. These are further grouped into categories of oppressor or oppressed.

While there are ideologies which hold that markers like race tell us nothing about who we are, critical theory asserts that group membership based on these markers is central to who we are.

Proponents of critical theory therefore also assign guilt on the basis of group membership.

The second premise is that the fundamental problem in society may be boiled down to unjust social structures and systems of power.

Societal issues such as unequal outcomes in wealth, wellbeing — essentially the oppression of all social groups deemed oppressed — are not due to differences in individual abilities or actions but primarily due to unjust systems and structures.

Proof of these unjust systems and structures lies not in the existence of discriminatory laws, but in the existence of disparate outcomes for social groups.

The third premise is that everything is about power. Critical theory interprets the world through a lens that perceives power dynamics in everything.

All forms of religion, philosophy, media, education and so on are seen as ways for people to maintain or obtain power over others.

This is also why critical theory advocates are suspicious of objectivity. The claim is that people professing to be neutral presenters of objective fact may be hiding their agenda to dominate through the language of supposed rationality and truth.

Taking the place of objective data is subjective lived experience, specifically, the lived experience of oppressed groups (although I have noticed this is not the case when lived experience does not align with the critical theory narrative).

For example, I have heard individuals from what would be considered as oppressed racial groups share their lived experiences that racism is not rampant today.

Proponents of critical theory, even those from racial groups deemed oppressors, disregarded these lived experiences as “internalised oppression”.

These three premises are commonly believed by those who subscribe to the specific form of social justice intertwined with critical theory, which I will refer to as Critical Social Justice (CSJ).

The CSJ movement is about the elimination of all forms of oppression, where “oppression” is defined by critical theory.

In action, this means to resist, disrupt and dismantle systems deemed as unjust by CSJ. This focus on liberation takes precedence over other moral duties, with some CSJ advocates justifying even violence to fulfil their goals.

THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE UNBIBLICAL

Now that we have an idea about what CSJ is, let us tackle its good and bad parts.

A positive aspect of the CSJ movement is its insistence that oppression is immoral and caring for justice is important.

As Christians, this should be something we definitely agree with.

After all, the Bible has plenty of verses that condemn oppression. Here are two for example:

- “Do not oppress the widow or the fatherless, the foreigner or the poor. Do not plot evil against each other” (Zechariah 7:10).

- “Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow” (Isaiah 1:17).

So, while we note that biblical definitions of oppression and justice are very different from CSJ definitions, Christians should always defend the vulnerable and care about doing what is just.

The issue I have with CSJ lies not in its claim to seek a more just society, but rather the approach it has taken to do so.

For example, many in the CSJ movement resort to various legal, social and economic pressures to try and silence anyone who does something they deem unacceptable.

Recently, I watched a segment of American TV show “60 Minutes” which aired this year.

The episode was on detransitioners — people who identified as transgender, medically transitioned, and later regretted it.

I saw this segment get flamed on social media afterwards. I even found out there was pressure from various activists to stop it from airing before it came out.

Call-out culture has resulted in many feeling fearful of expressing or questioning opinions outside of those deemed socially acceptable by the standards of the day.

While the segment itself was largely supportive of the transgender movement, that did not prevent it from receiving heavy pushback.

Many in the CSJ movement strongly criticised it because it featured the stories of detransitioners, which challenged the idea that the only answer for individuals who experience gender dysphoria is total affirmation.

CSJ has contributed to today’s unhealthy call-out culture where people are increasingly intolerant of different opinions.

This has resulted in many feeling fearful of expressing or questioning opinions outside of those deemed socially acceptable by the standards of the day.

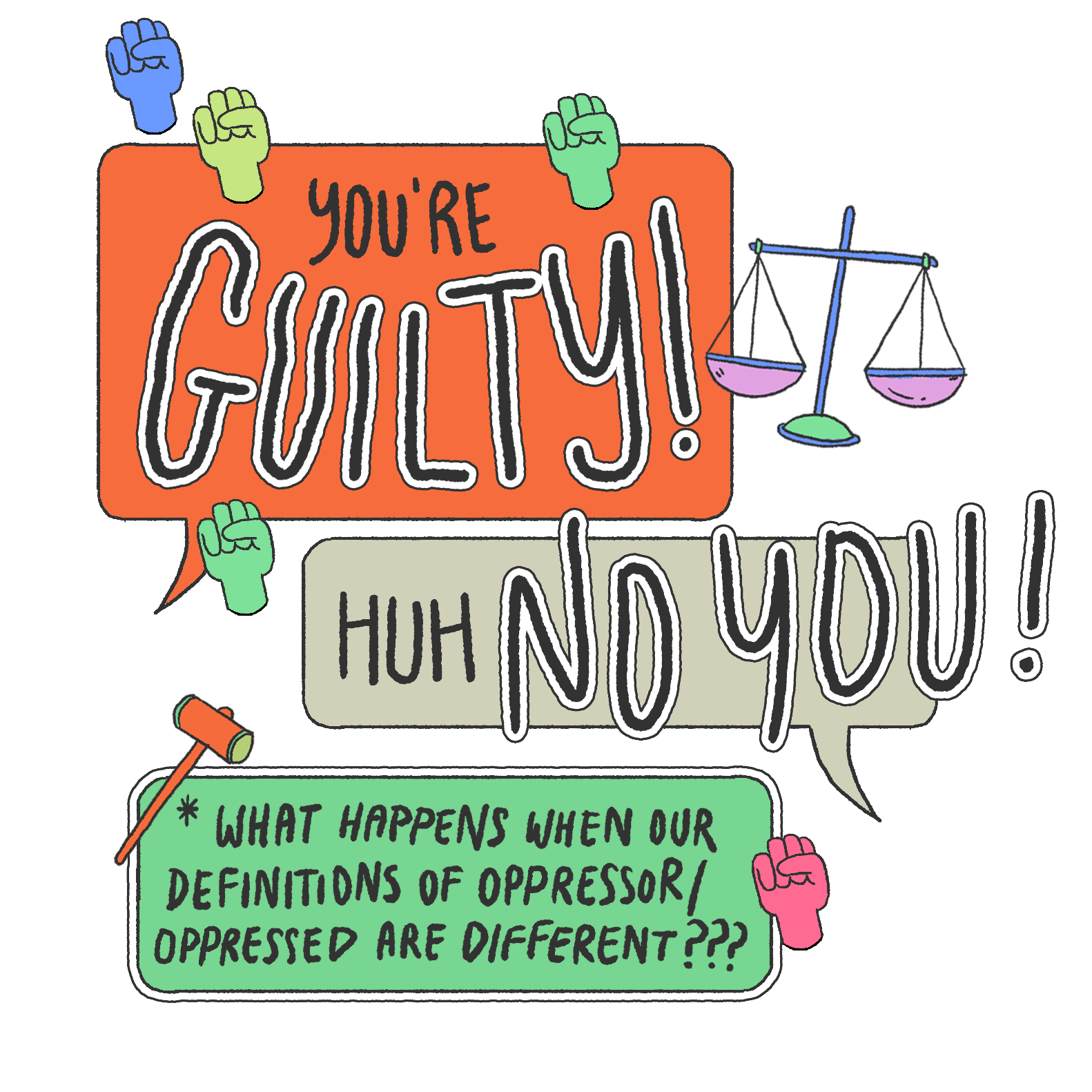

Another issue with CSJ’s approach is that it promotes moral asymmetry. Acts considered immoral when they happen to oppressed individuals can be moral if it happens to people in oppressor groups.

For example, I noticed that in certain CSJ circles on social media, it is morally acceptable for people to proudly declare themselves as misandrists and make extremely hateful statements.

This is seen as acceptable and at times even encouraged due to the different categories CSJ have placed men and women in. Men are the oppressors and women are the oppressed; women thus have every right to hate all men.

A primary way Christians move towards a more just society is by living righteously as Christ did, with the help of the Holy Spirit, according to God’s word.

On one hand, the source of CSJ’s moral asymmetry — anger from real and important issues such as sexism — is understandable.

On the other hand, I do not believe that justifies targeted hate towards individuals based purely on characteristics like sex.

This is especially the case for Christians. Holding individuals to different moral standards purely on the basis of their group identities is unbiblical.

All Christians are called not to repay evil for evil (Romans 12:17), but instead love our enemies (Matthew 5:43-44).

IS THERE A BETTER WAY?

In seeking justice, I believe the Bible’s approach is the best one. What exactly is biblical justice?

Firstly, biblical justice is God-centric. In the Bible, the words most often translated to “justice” and “just” can also mean “righteousness” and “righteous”.

So while secular forms of justice are based on changing human culture, Biblical justice is inseparably tied to God’s unchanging character and His standards of righteousness.

In fact, a main reason we care about justice is because God made humans in His image. As image-bearers of God, we are all equal before Him and therefore have the right to be treated with dignity.

Biblical justice also focuses on sin. While CSJ focuses on unjust systems of power, those with a biblical worldview see the main problem in the world as sin.

This focus on sin means that a primary way Christians move towards a more just society is by living righteously as Christ did, with the help of the Holy Spirit, according to God’s word.

Realising that the root problem is sin also means that for Christians, the end never justifies sinful means. That is to say, we should not support people or movements advocating for sinful behaviour in order to achieve what is seen as justice.

Another key aspect of biblical justice is its emphasis on being impartial.

The Bible calls for the application of the law and judgment to be free from preferential treatment based on identity markers like economic class or skin colour.

When God talked to Moses in Leviticus, He said: “Do not pervert justice; do not show partiality to the poor or favouritism to the great, but judge your neighbour fairly” (Leviticus 19:15).

Later, Moses also makes this clear when he appointed judges in Israel, telling them: “Do not show partiality in judging; hear both small and great alike. Do not be afraid of anyone, for judgment belongs to God” (Deuteronomy 1:17).

So, not only are we called not to favour those with more power like the rich when giving judgement, we are also told not to give preference to those with less power, such as the poor.

Biblical justice means judging every individual equally regardless of social category.

Furthermore, biblical justice is multifaceted. It can be retributive; punishing evildoers according to what they deserve and not any more.

Mercy and justice go hand in hand for God.

It can also be restorative, like seeking out vulnerable people who have been unrightfully wronged and helping them.

Justice in the Bible can even be merciful! Justice and mercy are seemingly incompatible, as one would usually have to set aside proper punishment in order to offer mercy.

However, mercy and justice go hand in hand for God. The just consequence of sin is eternal separation from God. Yet He extended His mercy to all mankind through Jesus Christ, whose death on the cross paid for every sin ever committed.

JUSTICE, FINALLY

As young person in today’s culture, I know how tempting it can be to jump on popular social movements, repeating their catchy slogans and being seen by our peers as someone “on the right side of history”.

However, as we live in a fallen world, issues of justice are often more complicated than we assume.

So when we discern how to act on justice regarding social issues, let us always keep in mind Paul’s warning: “See to it that no one takes you captive through hollow and deceptive philosophy, which depends on human tradition and the elemental spiritual forces of this world rather than on Christ” (Colossians 2:8).

In the face of injustice, we should always turn to God first. By the power of the Holy Spirit, let us live according to Jesus Christ’s example, in accordance with God’s laws.

As we do so, we hold on to the solid hope that Christ Himself will one day return to right all wrongs, administering final justice once and for all.

- How would you define justice?

- What are some verses in God’s Word that offer a biblical definition of justice.

- What is one issue of injustice on your heart today?

- What would a biblical approach to tackle this injustice look like?