“I don’t like Christmas.”

“No, thanks, Michael Bublé, I don’t care if it’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas.”

“I don’t need the presents, I’ll skip that Christmas gathering.”

“Can we stop with the carols in the shopping centres?”

Have you heard someone talk about Christmas in this way? Have you felt this way about Christmas? I don’t mean a Grinch or Scrooge who hates the festive cheer for festive cheer’s sake. I’m referring to those of us who find Christmas a difficult time, those who feel broken and hopeless in the days running up to it.

People seem to want you to be happy at Christmas – but you aren’t. I know even the Church seems to require you to be joyful at Christmas (just check the song lists for services in December). Yet, given your life circumstances, you just can’t. And I want to start by saying that’s alright.

But before you decide to skip your church’s Christmas service or cell group party, I also want to invite you to consider this little portion of the Christmas story.

BLOODSHED IN BETHLEHEM

“Then Herod, when he saw that he had been tricked by the wise men, became furious, and he sent and killed all the male children in Bethlehem and in all that region who were two years old or under, according to the time that he had ascertained from the wise men.” (Matthew 2:16-17)

Herod, King of Judea, is threatened by the birth of Jesus, the rumoured “king of the Jews”. He recruits the three wise men, who are looking to pay homage to baby Jesus, as his recce team to scout out the boy child’s exact location, but they eventually ditch the evil king’s seek-and-destroy mission after being warned in a dream.

That’s how we get to Herod’s holocaust – a massacre of Bethlehem boys. Few, if any, baby boys under the age of two would have escaped. Herod had the entire database of citizen information from an earlier population census (Luke 2:1-6), which is why Mary and Joseph were even in Bethlehem, Joseph’s hometown. No one could hide. This was a complete purge.

Bethlehem was not just the place of rejoicing over a Saviour’s birth. Its very streets flowed with babies’ blood and mothers’ tears. This is why Matthew tells us in His Gospel:

“Then was fulfilled what was spoken by the prophet Jeremiah: ‘A voice was heard in Ramah, weeping and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be comforted, because they are no more.'” (Matthew 2:18)

This part of the passage used to confuse me: Why was there weeping in this place called Ramah? Why is Jeremiah the Prophet even quoted here? And who’s Rachel?

Explaining the prophet’s words

In response to the brutality in Bethlehem, Matthew quoted a 600-year-old prophecy by the Prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 31:15), which was spoken at a low point of Israel’s history as part of a letter Jeremiah had written to the fallen nation for the people to read in exile. Grim, I know.

Context: At that point, God’s people were headed for Babylonian exile as judgment for their sins. Israel had rejected their God by choosing foreign idols. They lived as though God didn’t exist. Plus, even though Jeremiah had warned them to repent, practically no one cared. So then, Babylon invaded.

This is where Ramah comes into the picture. Ramah was a little town about 8km north of Jerusalem. It was where the Israelites were assembled to march into Babylonian slavery. The young, the pregnant, the elderly, the sick – everyone had to march almost 1,500km to Babylon.

It’s no wonder Jeremiah says, “Rachel weeps for her children”. Rachel was the second wife of Jacob, also known as Israel, one of the patriarchs of the nation. To the Israelites, she was the matriarch or the figurative mother of Israel. A mother weeping for her children, the people of Israel, as they went into exile.

Jeremiah’s words would transcend time, still ringing true 600 years later at Herod’s holocaust. Centuries after the horrific march to Babylon, Mother Israel would weep again with the many Jewish mothers whose sons were slaughtered in Bethlehem.

A picture of life amidst death

But here’s the strange thing. Matthew only quotes the bleak words of Jeremiah 31, but Jeremiah 31 in its entirety is actually a hopeful prophecy.

In fact, out of 38 verses in the chapter, only one verse – the Ramah prophecy – is a word of despair. The rest speaks of God’s promise to forgive Israel and the nations and initiate a new relationship with them.

“Behold, the days are coming, declares the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah… And I will be their God, and they shall be my people… they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, declares the Lord. For I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more.” (Jeremiah 31:33-34)

So even with Matthew’s citation of the Ramah prophecy of death, it also calls to mind the Jeremiah 31 promises of life.

The Jews, of course, were in dire need of real hope at the time of Jesus’ birth. They weren’t quite in physical exile, but they were in spiritual exile from God and hadn’t heard from Him for hundreds of years. 400, to be exact. Of course, His silence was their fault – God had said much through His prophets, but no one took heed. Now all the people had was silence. Darkness. Foreign oppression. Death.

How could Israel know their God again? How could Man be reconciled to Him?

The answer we see in the Gospels, appearing suddenly like a star in the sky, was not a political strategy for world domination. Instead, God gives us a baby borne of a virgin and two names: “Jesus” – for He will save His people from their sins (Matthew 1:21) and “Immanuel” – because God is with us once again (Matthew 1:23).

A video I believe will speak to those who need to see Christmas in a fresh way

HOLDING SPACE FOR DARKNESS

I wonder if you can see how Matthew paints a mixed picture of the Christmas story. A picture where two worlds collide: darkness and light; despair and hope; death and life. We must look at both at the same time.

Yes, the good news of Jeremiah 31 – all the great promises of God – will be fulfilled in Jesus Christ. Yet, all the warnings of God about sin and judgment, death and pain are realised as well (Matthew 5:17). Despair, darkness and death are the only reasons why hope, light and the life of Christ are sorely needed.

The name “Jesus”, He who will save people from their sins, has no meaning if we don’t realise we’re all sinful rebels needing a Saviour. The name “Immanuel”, God with us, means nothing if we don’t realise Christ had to become dust as we are (Psalm 103:14) so that we can become godlike – sons of God like Him.

Perhaps then, Matthew’s picture is what our churches need to reflect better at Christmas: not just light but also darkness; not just hope but also despair.

We definitely do celebration, thanksgiving and joyful carolling very well. These are important, of course. But there are those who really struggle at Christmas, and maybe our merry-making Christmas activities are not welcoming places for grief and sorrow at a time like this.

For some of us, Christmas is the cumulative flashback of a horrible year, months of spiritual darkness, sin and failure past. Perhaps it’s the first holiday we spend without a loved one.

For others, Christmas – like each New Year – is finding ourselves back at square one: life feels hopeless, the job search is futile, the medical treatments are pointless, the broken relationships are long gone.

Our Christian communities may not have provided the platform to share grief or ask for help, or not done it well, and I am sorry for the unintentional insensitivity you may have felt.

Maybe our merry-making Christmas activities are not welcoming places for grief and sorrow at a time like this.

Maybe this is why Matthew’s picture of Christmas matters. We learn from his strange quoted prophecy that Christmas can hold darkness in one hand, and light in the other. And all the more so, the Church can acknowledge the despair of Jeremiah 31 and pain of Bethlehem while rejoicing in the hope of Jeremiah 31 and promise of Bethlehem.

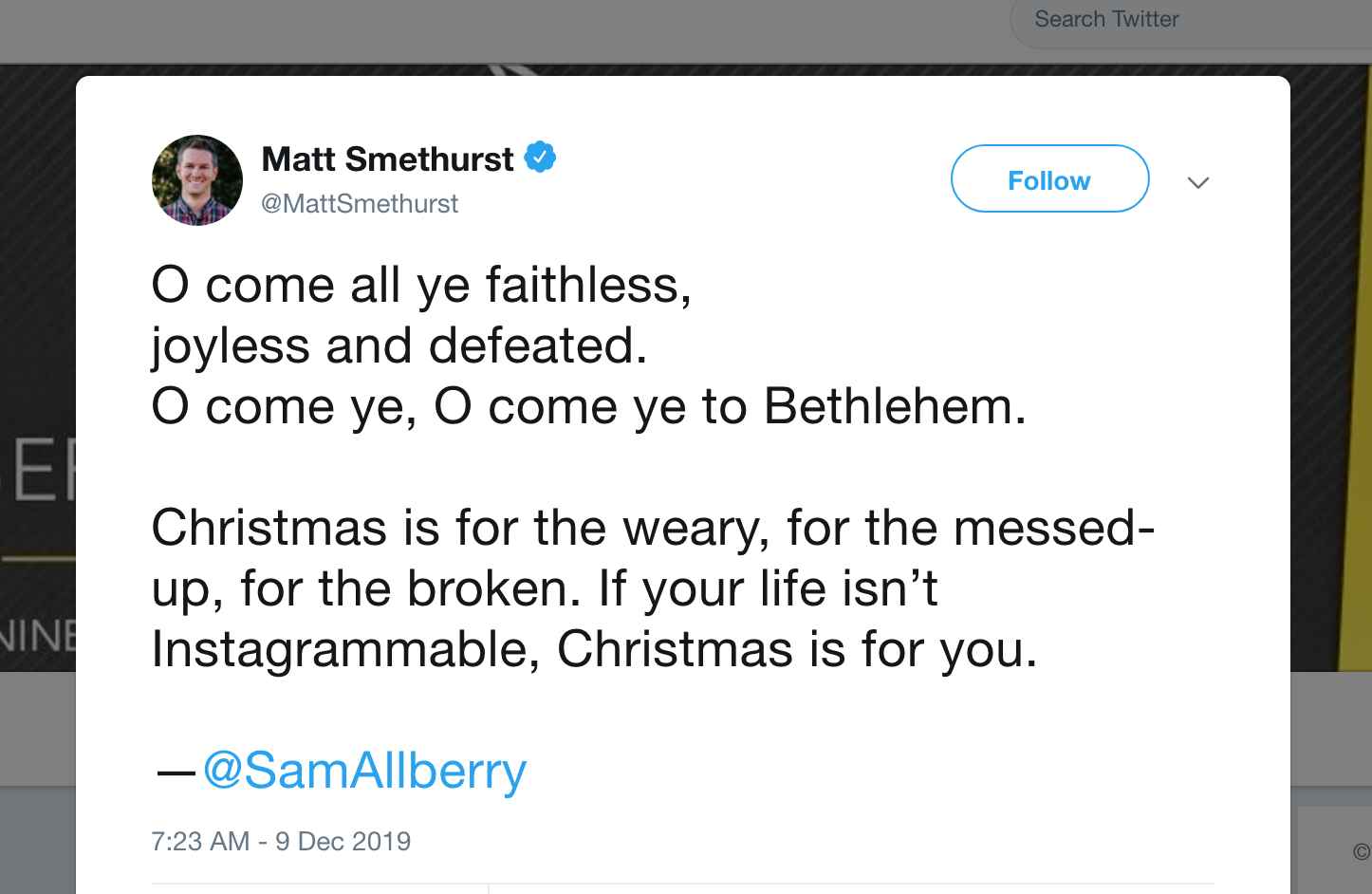

Despair and hope. Pain and promise. Light and darkness, not either-or. The Christmas story has space for both. It’s as though Jesus sings to some: “O, come all ye faithful, joyful and triumphant.” But He also sings to others, “O, come all ye faithless, joyless and defeated.”

If Jesus has room for both kinds of people, then the Church must welcome and hold space for both kinds of people.

My hope is that the Church can hold out these truths this Christmas and perhaps, instead of only asking “What are you thankful for this year?” or “What went well for you in 2019?” we can also ask gently, “How are you this Christmas?” or “What was difficult for you in 2019?”

And I pray that you – for those of us who find Christmas hard – will still go for your church’s Christmas service or cell group gathering, and find surpassing (and maybe surprising) comfort in the arms of Christ and His community.

“The King of Kings lay thus in lowly manger

In all our trials born to be our friend

He knows our need, to our weakness no stranger.”

(O Holy Night)

This article was adapted from Danny’s sermon at Zion Bishan Church.