When coming into contact with someone at risk, the last thing you’d want is for that person to feel like we’re pushing them away. But what if, unknowingly, our words or actions end up making a person feel even more isolated?

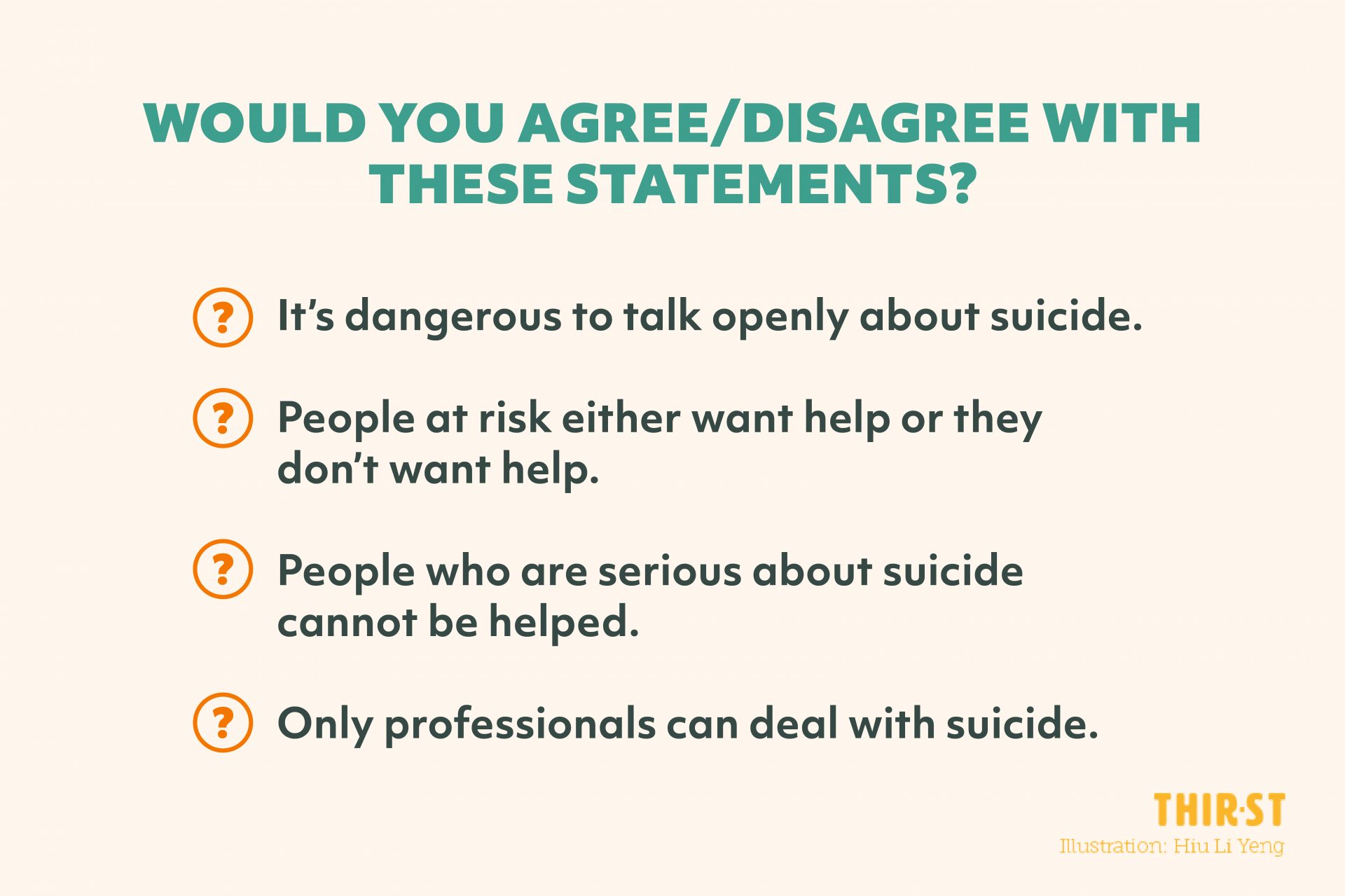

Before we try and help others, it’s important to “first examine our own values and attitudes towards suicide”, said Han Yah Yee, a social worker with 20 years of experience, at The Church and Mental Wholeness Conference at Yio Chu Kang Chapel on September 14, 2019.

We might not have given these much thought, but our answers to the following questions would powerfully impact how we respond to a person or situation. And in the case of a suicide risk, that could literally mean life or death.

Before we explore this emotionally charged topic, what are your thoughts on the statements below?

SHATTERING THE MYTHS

In her workshop, Han, who is the group director of social services at Montfort Care, sought to address common misconceptions about suicide.

We might struggle with asking someone very directly: “Are you thinking of killing yourself?” We worry that the question would encourage the person to entertain that thought.

“But by talking about it, the impact on the person is that they know that you’re quite prepared to talk about this scary, taboo topic,” explained Han.

“That opens our connection with the person at risk, so that they know if they want to talk about it, you’ll be the person that they can go to.”

However, how we phrase our question – down to our tone and body language – is equally important too. Instead of coming across as judgmental or flippant, what we should demonstrate is empathy.

Having journeyed with people who have attempted suicide, Han said that it’s possible for a person to walk away even when plans have been made.

That’s why each and every one of us have such a crucial role to play in “keeping someone safe – for now”.

From her experience, Han shared that most of the time, a person contemplating suicide is actually quite uncertain. There are two conflicting parts they struggle with – one part of them wants to die, one part of them wants to live.

“They say: ‘If only I can do this, then I won’t do that’… that’s ambivalence,” she observed.

By being there in that moment to have a different kind of conversation and offer hope, that could create more ambivalence and pull them back from the brink of death.

Professionals can come in to support the long-term recovery, but anybody can do the job of keeping that person at risk safe for now, Han stressed.

For the immediate circumstance, anyone who cares can make a difference. Moving forward, it will be our judgment call to get professional help and family support.

“The journey of recovery needs all of us,” she said.

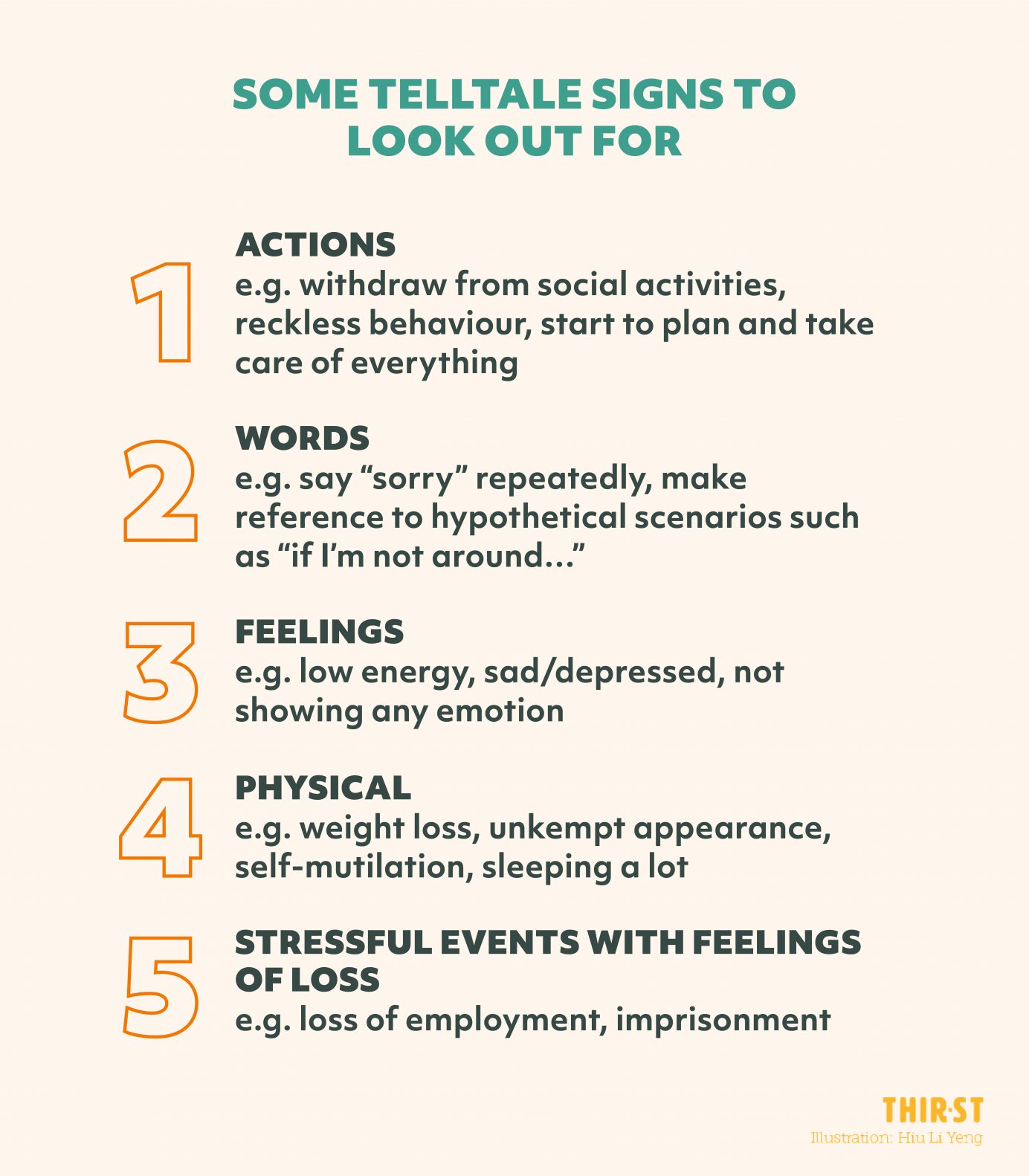

HOW DO WE SPOT THE SIGNS?

Many who are struggling might not be comfortable sharing, but here are some things to watch out for.

HOW DO YOU SPEAK TO SOMEONE?

Once you’ve identified a person at risk and that person shares that they are indeed thinking of suicide:

1. Find out if there’s already a plan and how it can be disabled safely

Ask: “So tell me what have you done?”

If they have already taken steps towards their plan, our role is to prevent that from happening. Mobilise family members, or in the worst-case scenario, admit that person to hospital.

2. Ensure that any alcohol, drug and/or medical concerns are addressed

Some drugs might increase the risk, so it would be in the interest of the person to make these less accessible. Figure out what is needed for safe/no use.

3. Contract an agreement, preferably verbally

For instance, you can say: “I’m very worried about you. I know some part of you wants to live and some part of you is still struggling, but since we’ve had this conversation, can you agree that until you have a better option, you need to keep yourself safe?”

That verbal agreement is important because it involves commitment. When the person agrees to it, it’s also a way for them to feel like they’re taking back some control in their life.

After all, we’re not talking about safety for long. It’s just for now until we can bring in professional help and link them to other resources for support.

LET’S ENLARGE THE LIMITS

The reality is that we won’t be able to be there for our friend or family member 24/7, Han pointed out. Being a caregiver can be extremely draining, which is why it’s a good idea to give the person at risk additional help options, such as SOS’ 24-hour hotline.

In the same vein, it’s also not wise to agree to keep someone’s suicide plan a secret, suggested Han, when asked about how one should handle confidentiality in such cases.

“Suicide cannot be a secret. It’s a public matter,” she said, adding that we would need to see how the information can be shared in a way that doesn’t disempower that person or make them feel violated.

“After you empathise and listen, give it back to the person and say: ‘I don’t think I can be the only one to know your secret because you need help and support. Can you choose at least one other person so that we can form a team?’”

In the cases of youth under 16 years old, Han said she would involve their parents because “safety comes first”.

The bottom line is: Suicide prevention is a community effort.

She said: “We shouldn’t do this alone. We should form a community that can come and support not only the person, but also the family members. So that the limits are bigger.”

If you’d like to speak to someone, help is available at the following centres:

Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) 24-hour Hotline: 1800 221 4444 or [email protected].

Institute of Mental Health’s 24-hour Hotline: 6389 2222

Care Corner Counselling Centre (English and Mandarin): 6353 1180

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800 283 7019

- Have you had a conversation with anyone on suicide? How did it go?

- How can you better empathise with someone who’s struggling?

- What steps can you take to bring hope and let someone know that they are loved?