When I teach a class on ethical issues, one assignment is for students to debate the topic: Is it ethical for Christians to fight in a war?

There are “neat” theological and historical arguments to be made on both sides of the topic, surrounding the traditional arguments such as on the Just War theory, pacifism and forgiveness.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine puts all those arguments into stark reality. The ethics of war is no longer merely a debate topic.

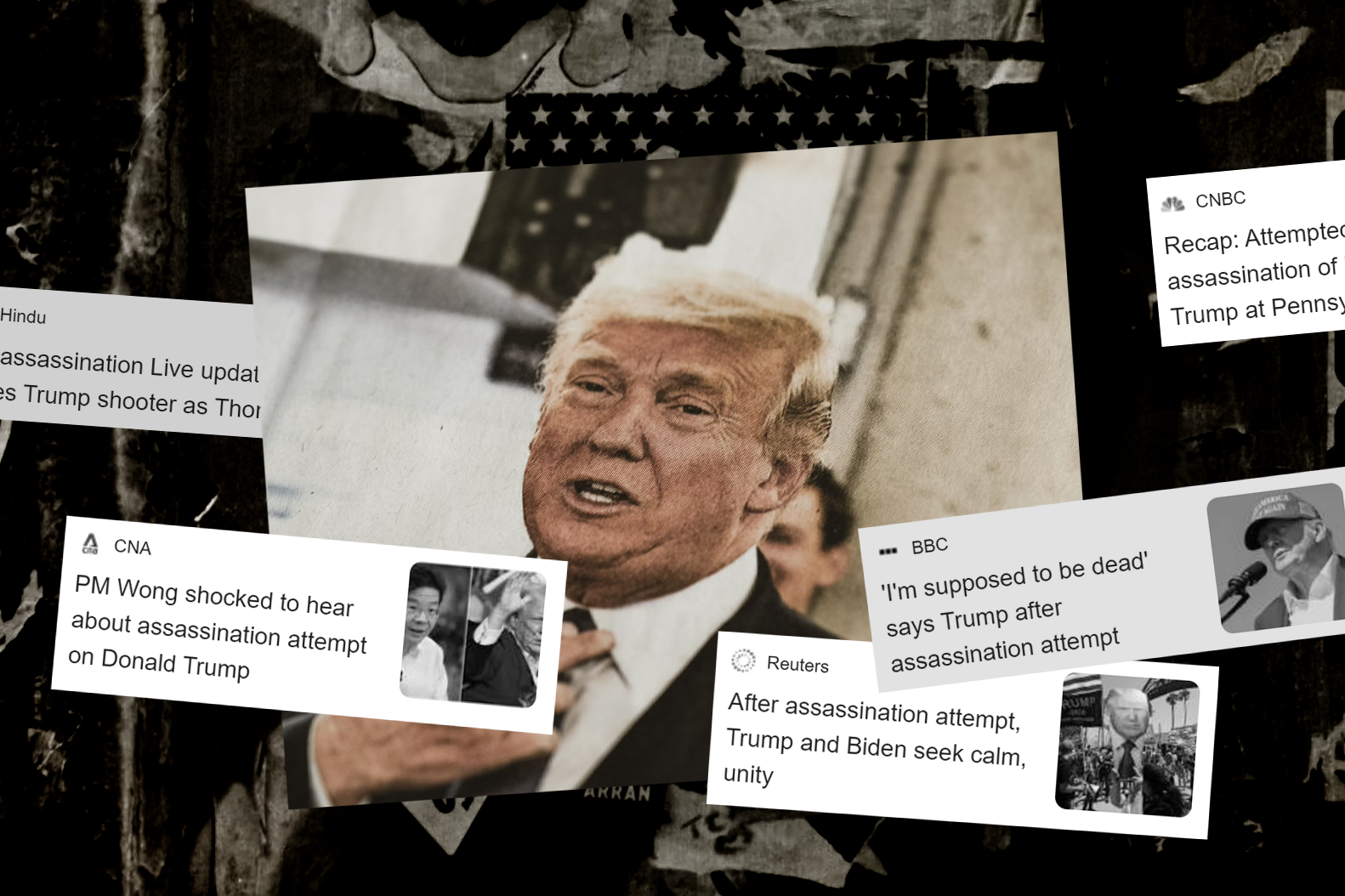

Intense media coverage has brought home the multifarious issues of war, and forces us to re-think all aspects of war and what “fighting a war” means.

In this war, there are battles fought in other arenas, for we can resist war without bearing arms and taking lives.

The boots on the ground

War is horrendous, bloody and utterly senseless. It is destruction by tanks, missiles and airstrikes. We have seen some of those horrors on the media.

And while the army fights, we also see videos of young women making Molotov cocktails on the streets of Kyiv and learning how to throw them. We read stories of ordinary people bombing bridges so that the Russian tanks cannot cross over.

The world looks on and nobody sends in armies to attack Russia or fight alongside the Ukrainians, though arms are being sent in.

In this war, there are battles fought in other arenas, for we can resist war without bearing arms and taking lives.

Ukrainian hackers are doing what they can to befuddle the Russian cyberspace. In sports, Russians were barred from taking part in the Winter Paralympics in Beijing for breaking the Olympic truce, a seven-day period of non-aggression before the Games begin and after its closing.

In the arts, Russians who are openly supportive of Mr Putin have been unceremoniously dumped from performances, while other musicians cancelled programmes in Moscow and other Russian cities.

Many governments have stopped trade with Russia, and some Russian banks can no longer use SWIFT, the global interbank transfer system. Visa and Mastercard have recently suspended their operations in Russia.

If the world cannot send in armed forces, this is what they can do.

Yet these also raise ethical issues about who fights in wars. Musicians? Athletes who have trained for years only to be barred from competition?

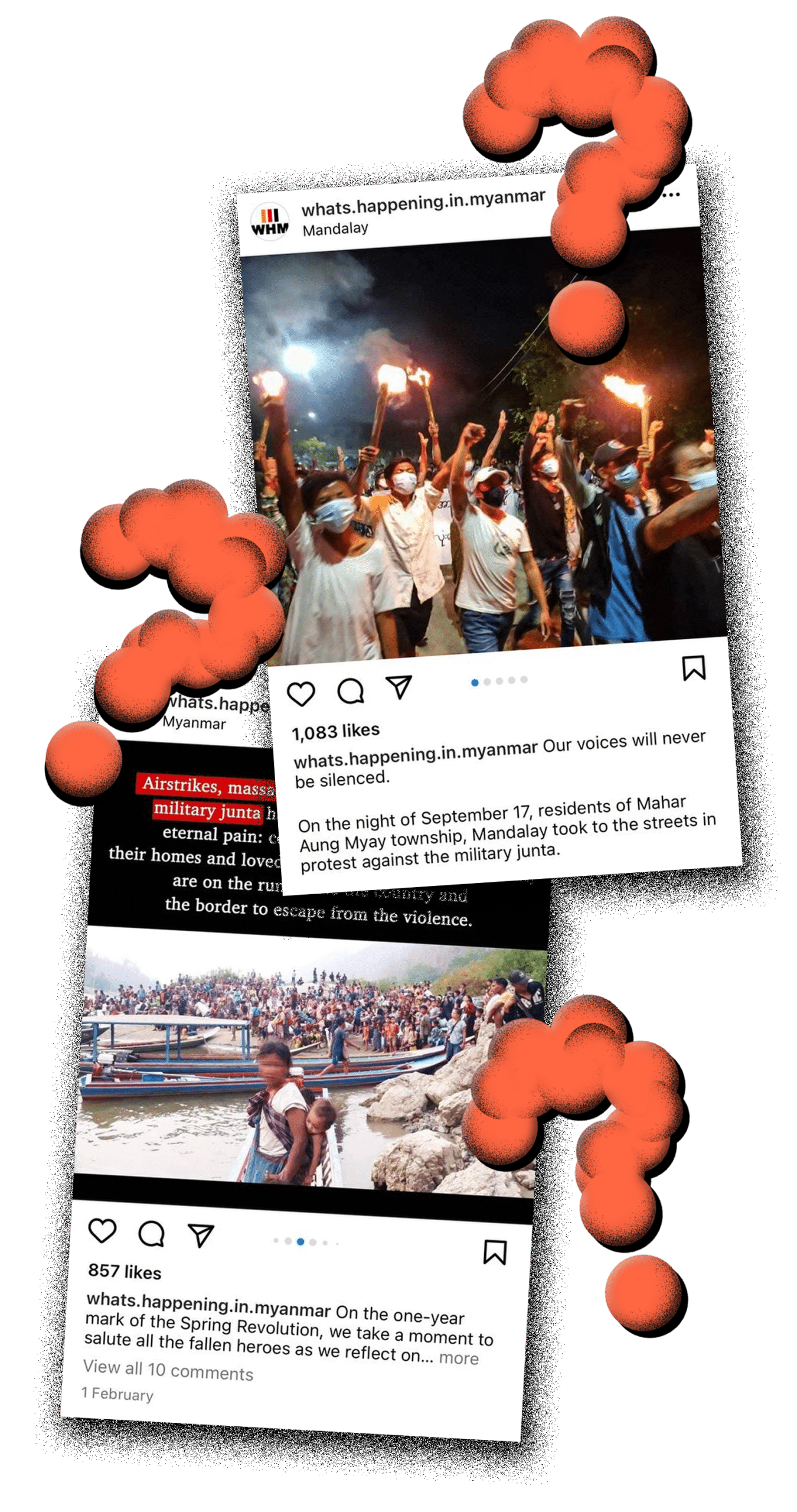

War is in the Ukraine, and there are also many other wars and other terrible injustices, such as in Myanmar and Afghanistan.

War is, and can be, fought at many fronts in order to bring aggressors to justice.

The collective voice of nations is another battle front: The UN has condemned Russia’s actions, and ASEAN continues to walk that difficult line of trying to engage the military junta in Myanmar, while holding them to account for their seizure of power.

Ukraine is facing a humanitarian crisis

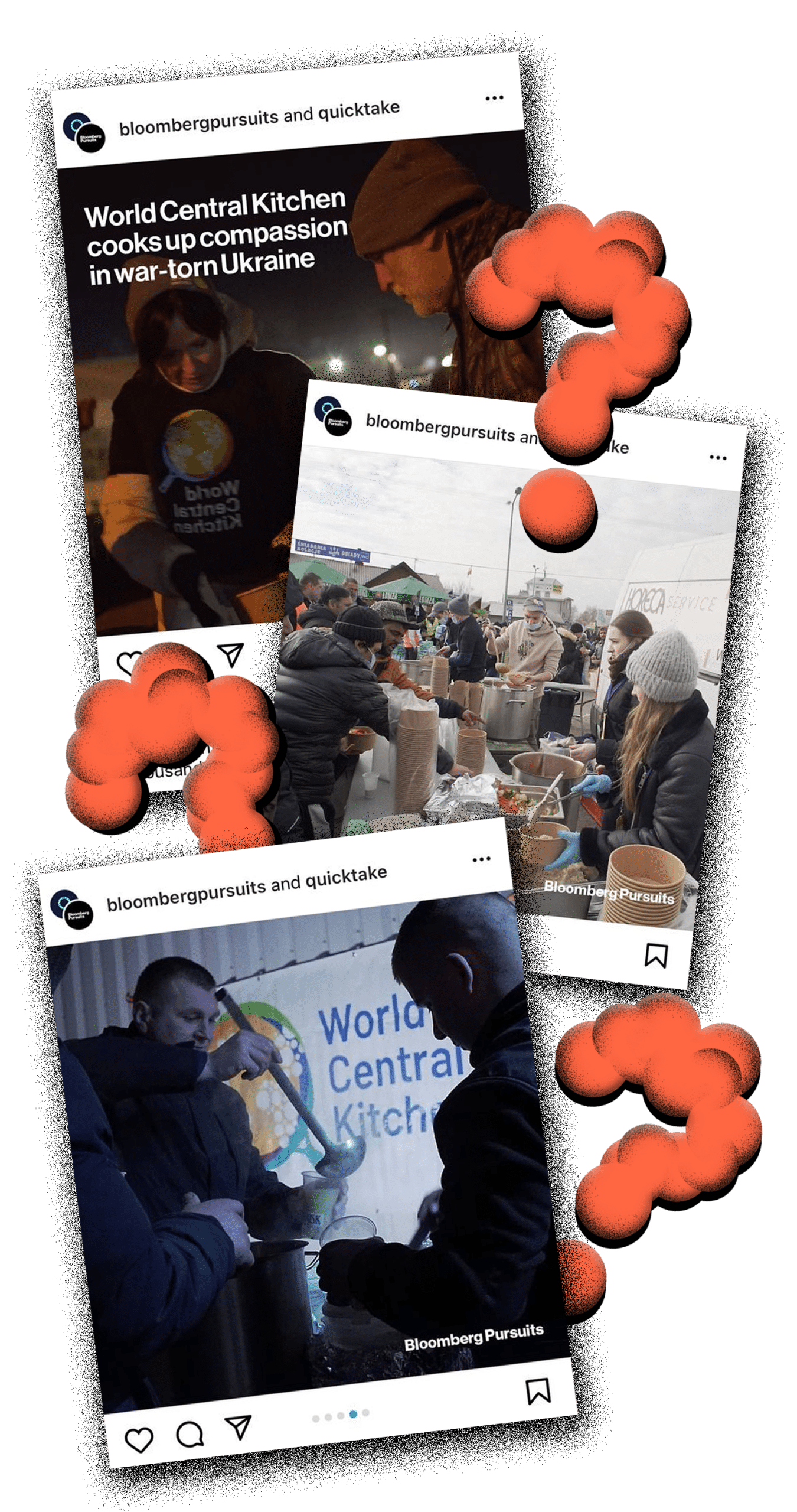

The Ukrainian humanitarian crisis has just begun.

Just 10 days into the fighting, it is estimated that more than 1.5 million people have fled westwards. International students are also trying to leave the country.

Many others continue to stay in the country, hiding underground. Soon there will be no power, no food.

I was moved that many Europeans are not only opening their borders, but also their homes to give refugees a home to stay in, even if it’s just for a while. This is just the beginning.

Europe, where so many, many wars have been fought, will once again face a humanitarian crisis. Maybe because of its history, there is an understanding and a steely resolve to be kind and humane.

If I were there, would I have the courage to open my arms and my home to refugees? I hope so.

Yet just about 10 years ago there was the Syrian refugee crisis, also in Europe. Would I have opened my doors to them? I hope so too.

But then after a while, the doors began to shut. In a while, will the same thing happen here? Only time will tell.

We’re forced to think about the theology of war

The complexity of war means that there are so many issues, thus there needs to be a variety of responses.

These issues force me to think deeply again about my theology of war (Matthew 24:3-8, Ephesians 6:10-12), suffering (Romans 8:18-30), presence and solidarity with the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:26).

Debating on the ethics of war is still a useful heuristic device for us to think about issues of Christians bearing arms, turning the other cheek and forgiveness.

Even when it’s so far away, we feel like we have to do something.

On one level we will soon have to pay for the costs for this war as it will affect Asia with rising prices and disrupted supply chains. Yet, many of us feel like we should do more to express our feelings of horror and helplessness.

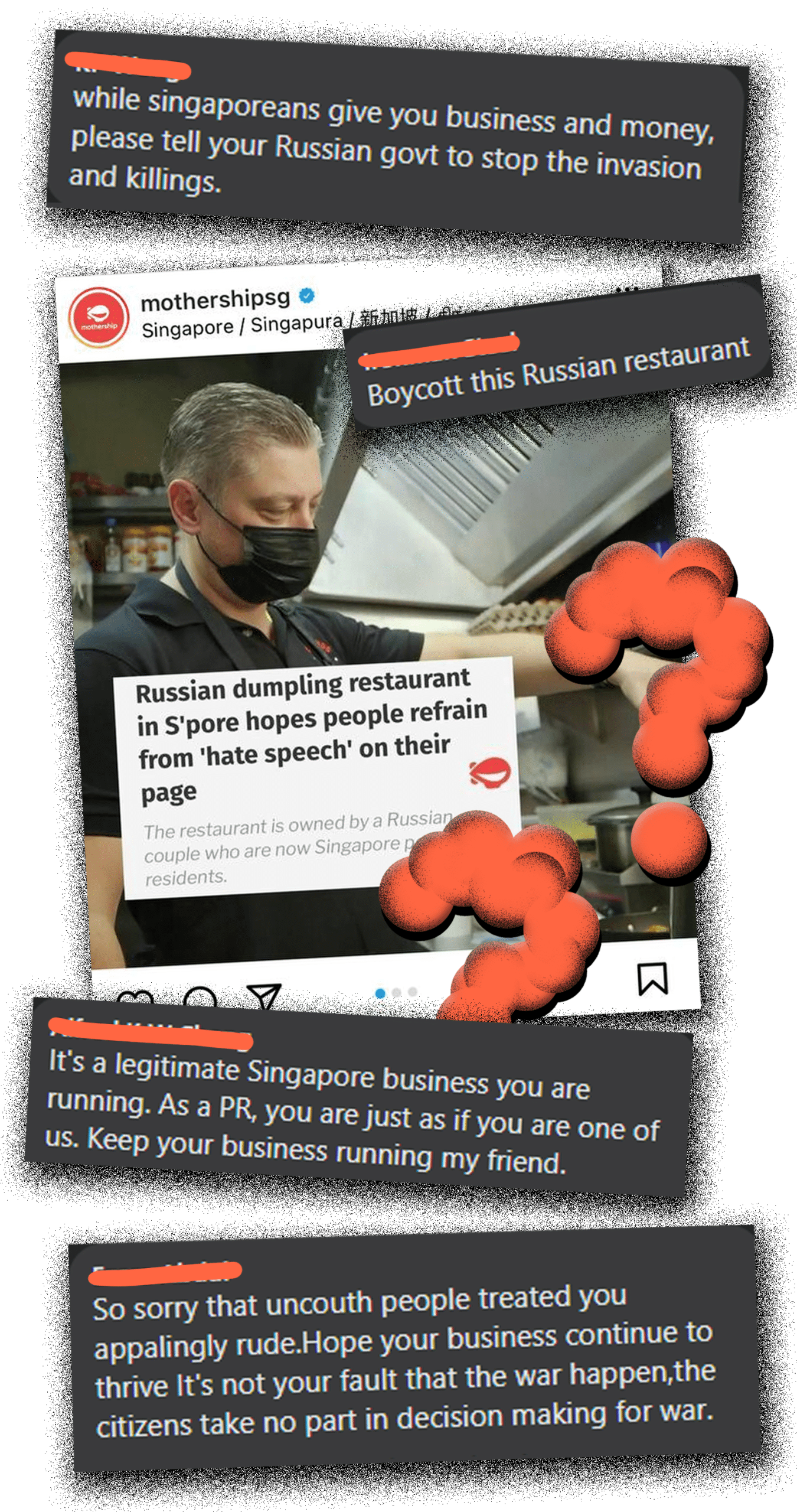

We pore over mainstream and social media, picking out interesting news items to share on our own page or to forward to others. It’s our way of showing solidarity with the invaded and displaced, and our way of fighting this bloody war.

I was disappointed that I did not have clothes in the colours of the Ukrainian flag, and then briefly considered wearing a coloured armband. I could definitely provide financial support to those who are giving relief at the borders.

For those of us who are in the position to do so, we could implement those restrictions and bans that governments have decreed.

Pastors and worship leaders should certainly lead congregations in lament and prayer.

Prayer is the only way we can try to make sense of this insane, bloody event.

Perhaps a day of prayer and fasting could be held, not just for Ukraine, but also Myanmar, and for this very broken world.

And, dare I say it, we should also pray for Russian leaders and citizens who are also caught in this quagmire.

Indeed, prayer is the only way we can try to make sense of this insane, bloody event.

Still, I feel that my prayer seems so pathetic and futile.

Praying tests my belief in a God who reigns, who sits enthroned between the cherubim, the King who is mighty, who loves justice and has established equity (Psalm 99:1-4).

I am forced to look beyond the here and now, to the not-yet, and to the coming again of the Alpha and the Omega (Revelation 1:8).

Debating on the ethics of war is still a useful heuristic device for us to think about issues of Christians bearing arms, turning the other cheek and forgiveness. It is helpful to be able to consider them while these are still times of peace.

We also begin to realise that while as citizens we may seek to forgive our enemies, that response may not apply at national or international levels.

For when we see the horrors of war, we realise how complex fighting in a war can be.

- What reflections do you have on the war in Ukraine?

- How have you responded to what you’ve read and seen so far? What else can you do?

- What injustices do you see around you, and how can you respond with compassion?