* MASSIVE SPOILERS AHEAD. SIGN AWAY YOUR RIGHTS TO A SPOILER-FREE REVIEW FIRST *

It’s hard not to watch Squid Game.

The setting is immediately straightforward and compelling: a masked, mysterious group of powerful people organise a survival competition that the poor and desperate take part in for a chance at a ₩45.6 billion cash prize (S$52 million).

It’s an idea that’s been done before, most recently in Alice in Borderland (also on Netflix, and recently climbing in rank). But Squid Game is a little more ruminant in its episodes’ thinly veiled critiques on class, systems and society.

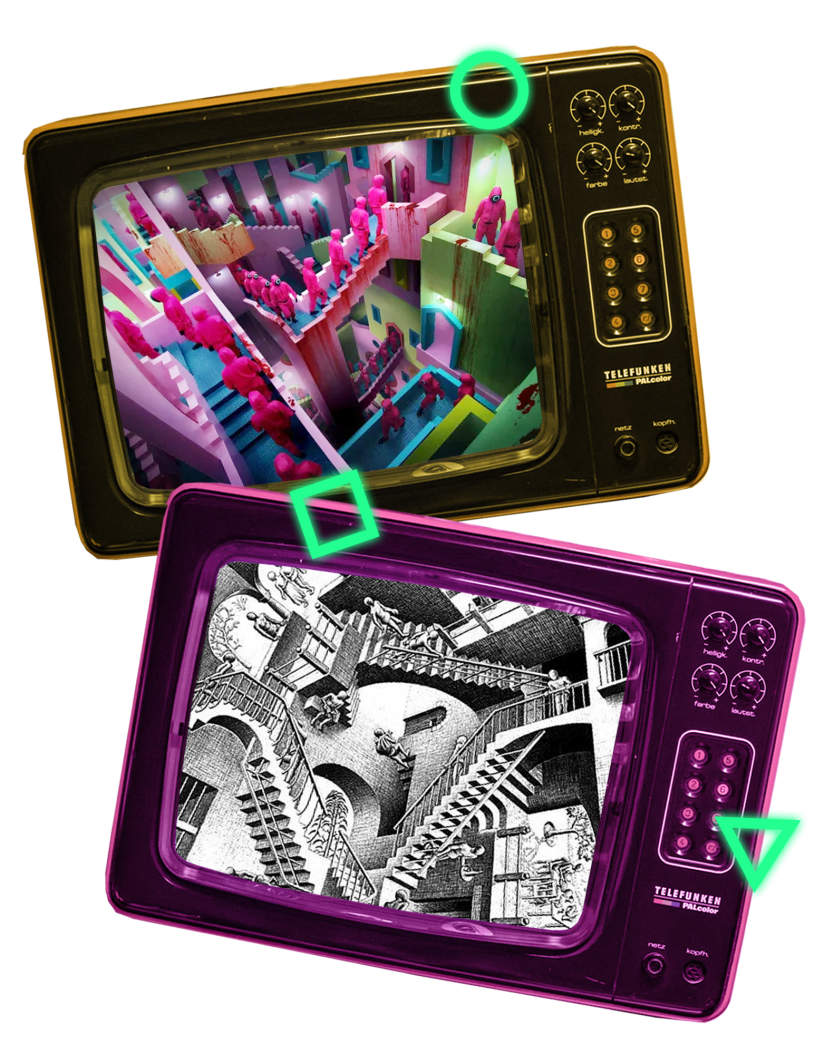

It’s also gorgeous. Fair play to the set designer for Squid Game. I don’t know who he or she is, but it was immediately apparent from Episode 1 that the show takes visual inspiration from MC Escher’s impossible artworks (see House of Stairs).

Thoughtful visual choices like this as well as a fantastical colour palette really serve to immerse viewers in a world that strides in tension between that which is realistic and human, and the surreal.

Having said that, it’s also hard to recommend it because Squid Game is not family-friendly.

It’s an M18 show. The worst of it comes from a sex scene in Episode 4 “Stick To The Team” involving Mi-nyeo (Kim Joo-ryoung) and Deok-su (Heo Sung-tae).

All you need to know is she promises she’ll kill him if he betrays her, a threat she eventually makes good on — now you can skip it!

Skips aside, however, if you’re under the age of 18, you should simply not be watching or discussing this series.

Other than that, as the show is about a survival competition, every episode has violent deaths. So, if you’re squeamish or do not want to consume media with any kind of sexual content, this show will not be suitable for you.

Nonetheless, if you’ve watched it or are still with me at this point, I’ll share what stood out for me in this gripping series.

THE CHOICES WE MAKE

One reason the show is so compelling is because of the choices confronting the characters on screen; the viewer is always invested as he waits through the dreadful lead-up to each character’s decision.

Whether that’s rooting for Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo) to share with his teammates what he knows about the honeycomb game in Episode 3; hoping Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae) would do the “right” thing and not cheat the elderly Oh Il-nam (Oh Yeong-su) in Episode 6’s marbles game; or wishing in vain that Sang-woo did hatch a plan to save both himself and likeable migrant worker Ali (Anupam Tripathi) — every choice in the show has absurd stakes attached to it.

And here’s the thing: Without realising it, viewers are also put in impossible situations and made to choose just like the characters.

We, who are watching this spectacle unfold, hold the line for what is humane when we choose what is right, even while the characters are dehumanised and slip into depravity with every subsequent game.

Sang-woo’s dreadful descent from a seemingly noble son and businessman who has made mistakes to ignoble betrayer and killer is one great example.

Most of us can do the easy and right things and look good (to those who are watching), until we have to choose whether or not to compromise when our own well-being is endangered.

Character arcs like Sang-woo’s are all the while contrasted against main character Gi-hun’s “rise”.

I found I was incredibly invested, rooting for someone who was on a redemption arc after a lifetime of bad decisions, and yet remained realistically prone to slip-ups when morally pressed.

That’s why it works — because the show grounds them in reality for the most part, and you’re always never really sure which way things might swing.

But just how much does Squid Game actually respect choice?

More than once, characters are reminded in times of distress that they had chosen to sign the “Disclaimer of Physical Rights”.

They were the ones who chose to play the games, and later — after Player 1 delivers an “impartial” swing vote — to return to them.

What might not be as immediately apparent can perhaps be perceived from asking the question of just how much agency these characters actually have in their system and society.

Gi-hun is asked at knife point to sign the indemnity form. The vast majority of players face insurmountable debts and real threats outside of the game world — the choice to take part in the games is no choice at all.

“Out there, I don’t stand a chance. I do in here,” laments one of the players early on in the series.

As such, when the curtain is drawn and the violence escalates, we learn that the game and its mysterious promoters only offer the illusion of choice.

Join or die. Progress or die. Win or die. It is a damning indictment on the rat race that dehumanises and drives one to despair.

Again, the sets on the show work brilliantly to accentuate such points.

Think back to the visuals of players walking up and down the impossible maze of stairs. Where else is there to go? Just one foot in front of the other, on an impossible path set before them.

The series mocks the futility and dehumanisation rampant within a capitalistic society’s rat race; players only ever see the back of the person right in front of them, who in turn see the same.

THE VALUE OF A LIFE

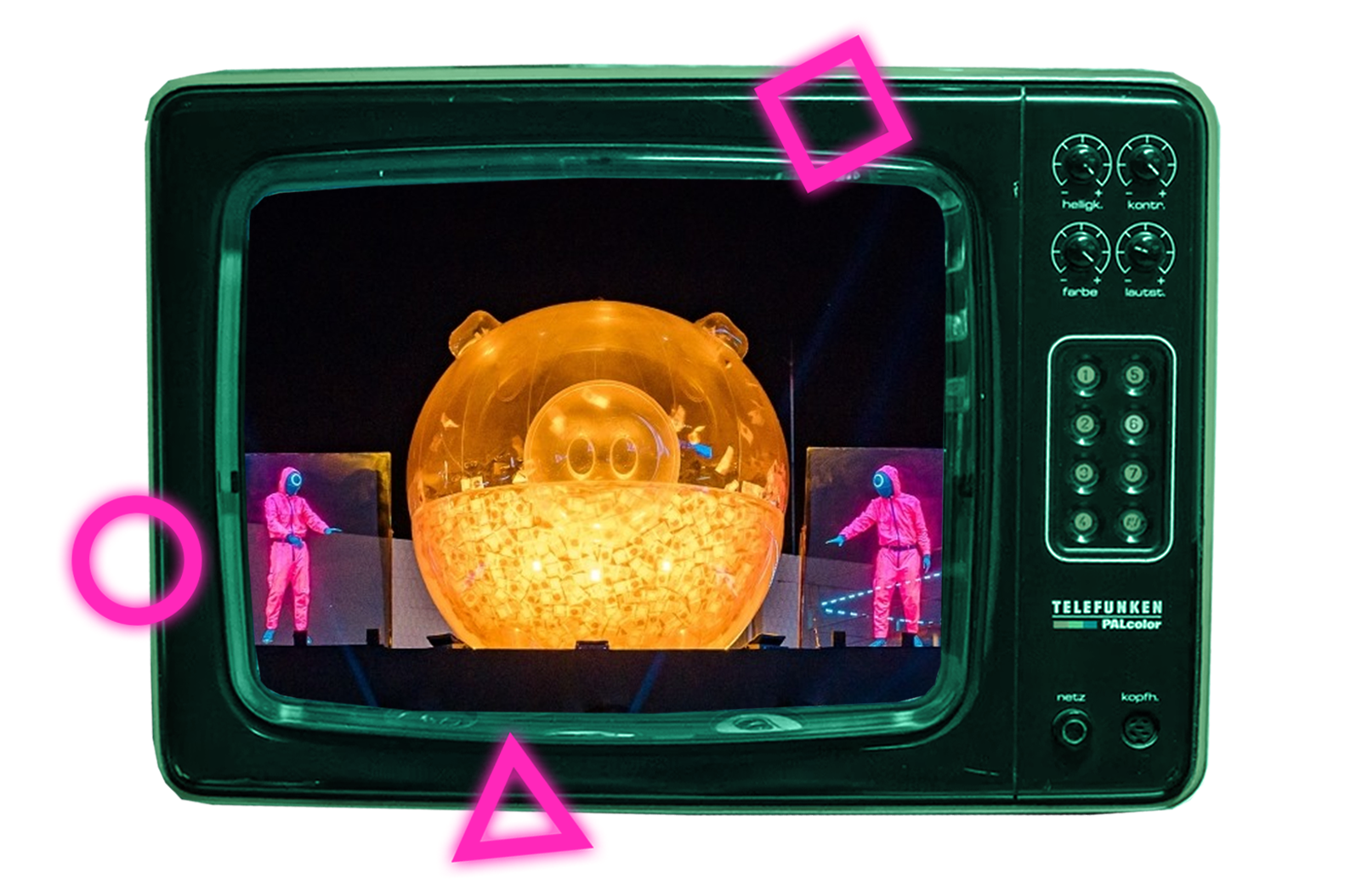

There was one other thing in particular that struck me over the course of the series: as the value of the prize money grows, the value of a human life decreases.

This inverse proportion is driven by the fact that for every player eliminated (killed) in the competition, the pool of money grows by a hundred million won (S$114,421).

Each death results in wads of cash being unceremoniously dumped into the huge acrylic piggy bank that hangs over everyone’s heads (there’s another heavy-handed comment here I’m unwilling to expound on).

But when this happens, to chiptune music, no less — there is a callous, almost vaudeville nature to the proceedings that make light of the very tragedies that have transpired them.

In our terms, $114,421 is how much the organisers have decided a human life is worth.

And the cruel catch is, the remaining players do not win anything if the majority chooses to end the games. Instead, the prize pool would be split up and go to the deceased players’ families.

So, we see a sort of sunk cost fallacy as the series progresses. “If we stop right now, that only helps the ones who are dead,” yells Player 322 in Episode 2.

This idea that they have come too far to stop is taken to the extreme by the end of Episode 8 where only three players remain, and Sang-woo stabs Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) to prevent a majority from being formed that would end the game then.

Ironically, it is Gi-hun of all people who comes to understand the worth of a human life.

He goes from gambling (a state of complete disregard for worth and value — the highest order of sunk cost fallacies) and taking advantage of his mother and daughter’s lives and kindness, to becoming the only person in the room who understands — for the most part — that a single life is worth more than any amount in the world.

“A man just died! We shouldn’t be killing each other like this!” he yells in Episode 4, after Deok-su kicks a fellow player to death over a meal that amounted to an egg and a beer.

Through sequences like this, the show really challenges viewers’ conceptions of worth and value. What is a person worth? And to whom? What really matters in life at the end of the day?

Unlike the participants, I certainly had plenty of food (for thought).

Anyway, back to Gi-hun.

After seeing more and more lives being worthlessly sacrificed through the course of the series, Gi-hun ultimately chooses to give up the prize money at the very last game in Episode 9 in order to spare Sang-woo (whom he had bested in a brutal knife fight).

However, Gi-hun still ends up with the prize money when Sang-woo kills himself in shame.

The prize money, that was meant to help his mother and daughter lead better lives, ultimately ends up being completely useless and worthless to Gi-hun, who returns home a multi-millionaire only to find his mother had died alone and his daughter had already migrated to the US.

Apart from drawing an initial 10,000 won from the card that gives access to the prize pool, Gi-hun cannot bring himself to touch the blood money and opts to live like a vagrant instead.

What was it all for?

THE BETTER PRIZE

As I watched Squid Game, I often paused to wonder what the value of my life would be. Mix around with certain friends, and you might hear terms like “net worth” being thrown around.

When I was younger, I used to place my value in stuff I could achieve. Like the kind of results I got at school, or whether I could get into the jobs I wanted.

Now that I’m older, I still catch myself doing it. Happens occasionally when I look at my investment portfolios (thanks, China). Or the times I subconsciously or mistakenly think I only have worth if I’m of use to God or His kingdom.

As a Christian, it is comforting to know that God has already decided my worth (it’s a lot more than $114,421!).

After all, our prize is not the world’s prize.

Somehow, in God’s strange economy, my worth is equal to the very life of Jesus Christ, who gave Himself and died on the cross for my sins.

A Person has paid the price for our prize (John 3:16).

It’s comforting to know that someone exchanged His life for mine (Romans 5:6-11). To know my worth is unshakeable in Him.

So my existence doesn’t hinge on a hamster wheel, endlessly racing to add a few more zeroes to my portfolios.

Sure, we’re in this system. But we can still play it smart, play it right without losing ourselves and becoming slaves to empty gods.

Maybe even meet some people along the way and have conversations about things that really matter.

Because unlike the players in the game, we do have a choice (Romans 10:13).

Money, man. It’s never enough.

And as the series shows, even when you do get it, there’s no guarantee you’ll be able to fix the problems you thought you needed the money for.

So, I guess I’m taking a look at my own life. At all the stuff you can’t really put a price on like family, friendships and faith.

What if it’s the invisible, intangible things that really have lasting value? Not loud and shiny things, not piggy banks and grandiose ideas that hang over our heads?

What is really of worth are the everyday things that flash by all too easily if you let them. The things that count for eternity.

Those are the things I want to choose. They are what I’ll chase and invest in instead.

All screenshots sourced from Netflix’s Squid Game.

- What are the things you value in life?

- What will you give up or what have you given up in pursuit of these things?

- Have you ever wondered what happens after your life on earth ends? How will that affect the way you live now?