“My mum would tell me when I was younger that I needed to study hard and be a tuition teacher, so I can ask my students to come to my house and I can earn a lot of money without having to go out at all,” remarked Alister Ong with a hearty laugh.

His dad was even more direct. He wanted Alister to enter the finance industry so that he could work from home: “You can use your brain, that’s all that you have.”

Alistair found that both suggestions had a common similarity:

- Earn a lot of money

- Don’t step out of the house

And as someone with a disability, Alister understood his parents’ concerns: “How would other colleagues treat me? Will there be any companies or organisations that are willing to employ someone with a disability?”

Alister, 27, was born with cerebral palsy, a condition that affects his motor skills.

Growing up, he couldn’t walk or run. These days, he gets around with a motorised wheelchair.

His parents’ concerns were not unfounded. Employment is a big worry for many who live with a disability.

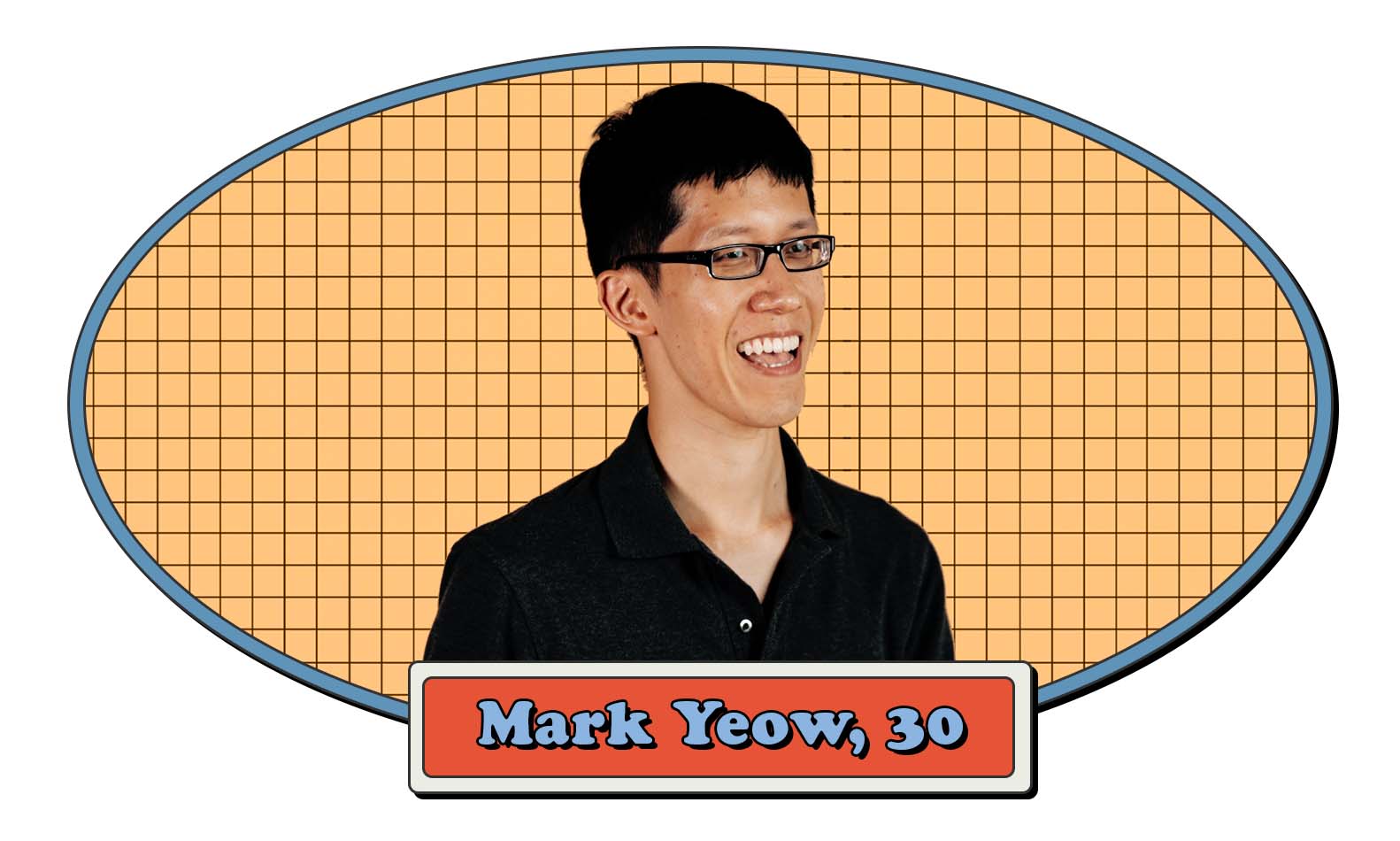

Mark Yeow, 30, put it this way: “My biggest concern is that I would be a burden. That I would be unable to work, unable to contribute productively.”

He was diagnosed with glaucoma at age 22, a medical condition that results in blood flow and oxygen being cut off from the optic nerves, leading to a loss of vision.

To date, Mark has lost about 40% of the field of vision in his left eye and 10% in his right. There is no cure for this condition.

Vanessa Tan, 41, who was born deaf, echoed similar sentiments as Alister and Mark.

“My life was limited by my disability because some companies do not accept my deafness,” she shared.

“I struggled with my meals when I was jobless, but I managed to live with my savings.”

DISABILITY ≠ DEFECTIVE

Employment opportunities for persons with disabilities (PWDs) are often inhibited by the mindset that they are limited in the things they can do.

“A common misconception for persons with disabilities is that persons with disabilities can’t do much,” Alister started, admitting that he used to think that of himself too.

As he grew up, however, Alister came to see that he doesn’t just need to rely on others and receive all the time — he can give and be a blessing too.

This revelation came when he was sharing his life story in a youth camp in Indonesia.

“Hearing your story, there is a renewed sense of purpose and hope in my life also.”

“There were youths coming after me to tell me, ‘Alister, I’m very impacted by what you’ve shared just now. And knowing and hearing your story, there is a renewed sense of purpose and hope in my life also’,” he recounted.

“It touched my heart to see that as a person with a disability, I don’t have to always receive help – and I’m happy to receive help – but I can contribute to others and give to others also.”

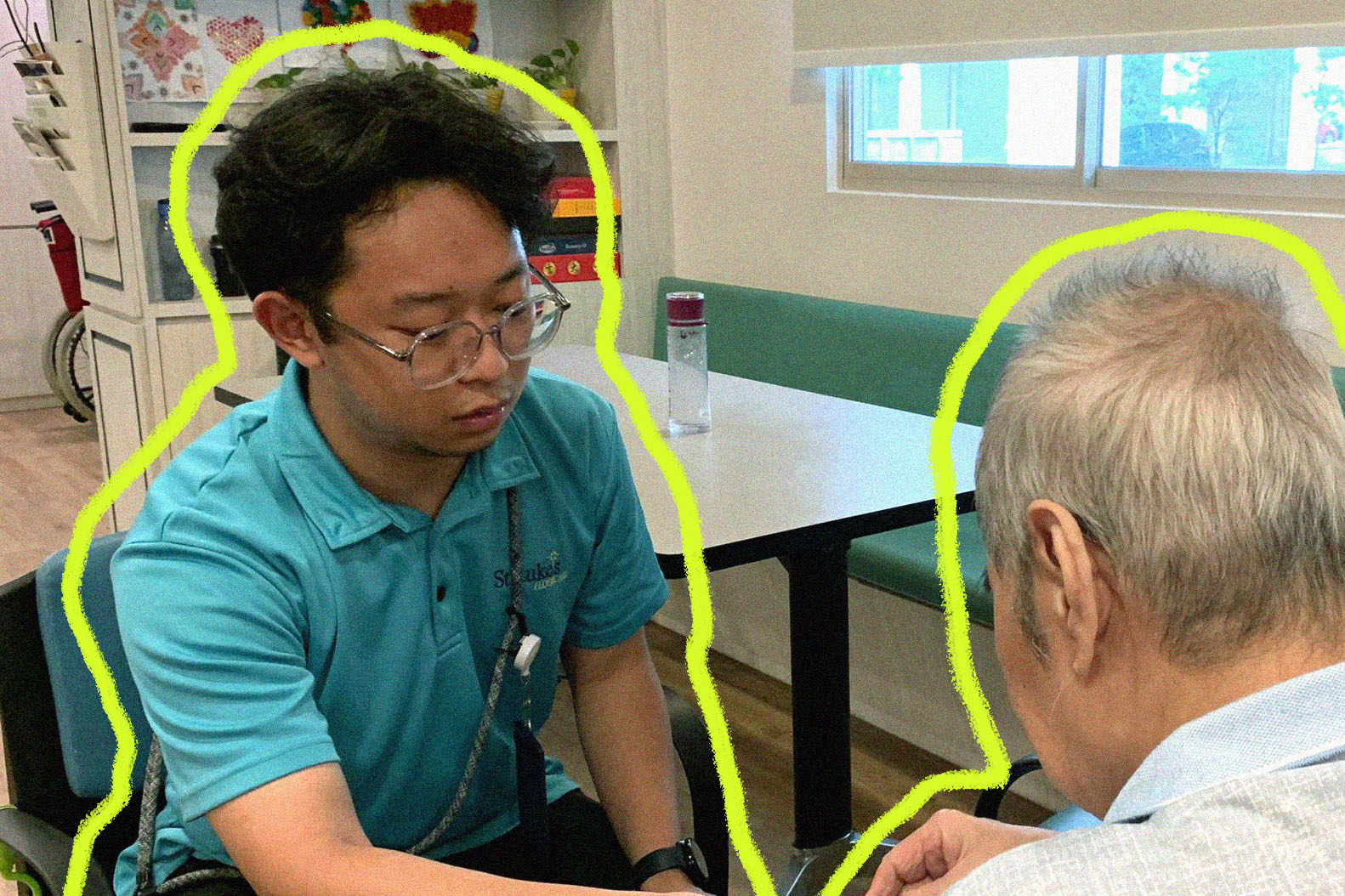

These days, Alister is working as a Diversity and Inclusion Champion. He goes to companies and organisations to advocate and spread awareness for PWDs – not quite what his parents expected him to do, he noted with a chuckle.

Even though Vanessa was also at a disadvantage during her educational years, she managed to work around her disability to get where she is today.

“One of the difficulties was that all my lecturers gave their lectures without any interpretation provided,” she shared. “I also had to study all the modules by myself because I was a deaf student among hearing classmates in my class.”

Thankfully, she had some help from her classmates and lecturers who met her after classes to go through the materials again.

Vanessa eventually graduated with a diploma from Singapore Polytechnic despite the challenges she faced. She is now a Digital Imaging Executive at a local landscaping company, proving that PWDs can do well in society as long as they are given the chance.

The mindset that PWDs are limited doesn’t just affect employment opportunities, but their sense of self-worth also.

“When people are not familiar with what it is like to live with this condition, they tend to look in from the outside and frame you within your condition. They tend to associate that with your identity,” Mark explained.

“For that to happen, it sometimes feels reductive,” he continued. “And sometimes, the more you hear that, the more you start to take that on for yourself.”

Mark elaborated that for a long time in his life, he too, began to define himself by his condition like “glaucoma sufferer” or “the guy who’s going blind”.

But he eventually came to the conclusion that while this condition is a part of him, it is not the part of him.

“It’s just like how we do not want to be defined by the jobs we hold or our marital status or our ethnicity or anything like that. That’s not what makes us who we are.”

WHAT HURTS THE MOST

Another challenge that comes with having a disability is having to deal with rude behaviour by others.

Vanessa shared that there have been times when people would slam their hands on her table to get her attention because she could not hear them.

“They used so much force that I could feel the vibration from their slamming of my table,” she recalled.

“The way they behaved caused me to get angry at them many times. A person with respect would have waved to me gently, tapped me on my shoulder or knocked on the table gently to get my attention.”

For Mark, the insensitive treatment he experienced was not as explicit. But that doesn’t mean it hurts less.

“I get a lot of people who, every time I go through something, would ask, ‘Does that mean you’re getting better, does that mean you’re healed?’” he recalled.

“And I’m like no. That’s the thing with chronic conditions. They don’t go away.”

Others would also forget how his condition limits him: “Sometimes I get to thinking, why do people keep forgetting that I can’t drink coffee? Or why do people keep forgetting that this doesn’t get better apart from a real miracle happening?”

Worst of all, however, is when some even tell him to “have more faith” to be healed.

“You know it’s not because people are malicious about it. It’s just coming from the top of their minds. It’s just people saying stuff, making conversations,” he said. “But sometimes it cuts deep.”

For Alister, on the other hand, it is the lack of conversation that has been unhelpful to his situation.

He recalled a moment when he was in the lift, when a family with a young boy entered with an empty stroller.

This young boy was “jealous” of Alister because he had to walk on his own and could not be pushed around unlike Alister in his wheelchair.

He recounted: “The little boy actually said: ‘Mummy, why can he sit in his stroller but I can’t?’”

While Alister had found the comment hilarious, the little boy’s parents immediately tried to hush him.

“Don’t look, don’t point, keep quiet” was how Alistair summed up their approach, and was ironically what he did not appreciate in that encounter.

However, Alister acknowledged that society has improved in terms of engaging in such conversations.

These days, when children express interest in his motorised wheelchair, parents would address the elephant in the room.

“They’d say, ‘Yes, that’s a wheelchair. Say hello to kor kor (older brother),’” he shared.

“I thought that was very good, because children at a young age are learning how to interact with persons with disabilities and that it’s okay to have open conversations about these kinds of things.

“We don’t have to be hush-hush about it.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

So how can we do better as a society?

“In a word, my answer would be to learn,” offered Mark. “And to ask the questions.”

His caveat was that questions asked shouldn’t just remain at the superficial level — people need to have the inquisitiveness to want to know more.

“The more these questions get asked, the more productive that conversation becomes,” he shared. “And the less likely it is for people to make mistakes or to commit offences to those who have these conditions.”

Vanessa had similar sentiments. She expressed that people should be open to find out about issues from deaf persons directly before making any assumptions.

She also hoped that people would be open to communicating with people with hearing impairment in non-verbal ways, and give PWDs a chance to show their abilities or learn new skills.

Finally, Alister took the chance to conclude the interview on a note of encouragement to PWDs: “I would encourage you to step out of your comfort zone, to be bold, be brave, be confident.

“Continue to rise above your challenges and to look at the positive side of things.

“We have different strengths, different abilities. We can give and contribute to society as well.”