Have you ever considered learning the languages the Bible was originally written in? After all, it wasn’t written in English — almost the entire Old Testament was originally written in Hebrew!

It’s not all Hebrew though: a few chapters in Ezra and Daniel, and one verse in Jeremiah, were written in an ancient language called Aramaic. And when it comes to the New Testament, that’s initially written in Greek (though Jesus likely spoke Aramaic).

Interestingly, the language seen in the New Testament is called Koine Greek, where “Koine” (pronounced coin-ey) means “common”.

Koine Greek is not the same as classical Greek. Classical Greek was what ancient philosophers such as Aristotle and Plato used. Rather, the Bible used everyday language.

The language used in the Bible is also different from modern Hebrew and Greek used today. Modern Hebrew and Greek as we know it today had their roots from the 19th and 20th centuries.

Today, there are so many more languages across the world than just biblical Hebrew and Greek; as of September 2023, the whole Bible has been translated into 736 languages to reach the ends of all nations.

English alone has over 100 translations. From the New International Version (NIV) that we know and love, to the Amplified Bible (AMP), there are so many versions we can choose from.

Given that we Christians have access to so many versions of the Bible, one might believe that studying biblical Greek or Hebrew no longer serves any purpose. But, well, Dr Yee Chin Hong (Trinity Theological College) would beg to differ.

Why should we study the biblical languages?

Dr Yee tells me that learning the biblical languages helps him to appreciate God’s Word better.

The Bible has many nuances and literary devices that are only more apparent in biblical Hebrew and Greek. One can never fully capture the nuances in one language and bring them over to another.

Thus, Dr Yee finds knowing biblical Greek and Hebrew to be extremely helpful for his understanding of God’s Word, and for being able to explain it to his congregation.

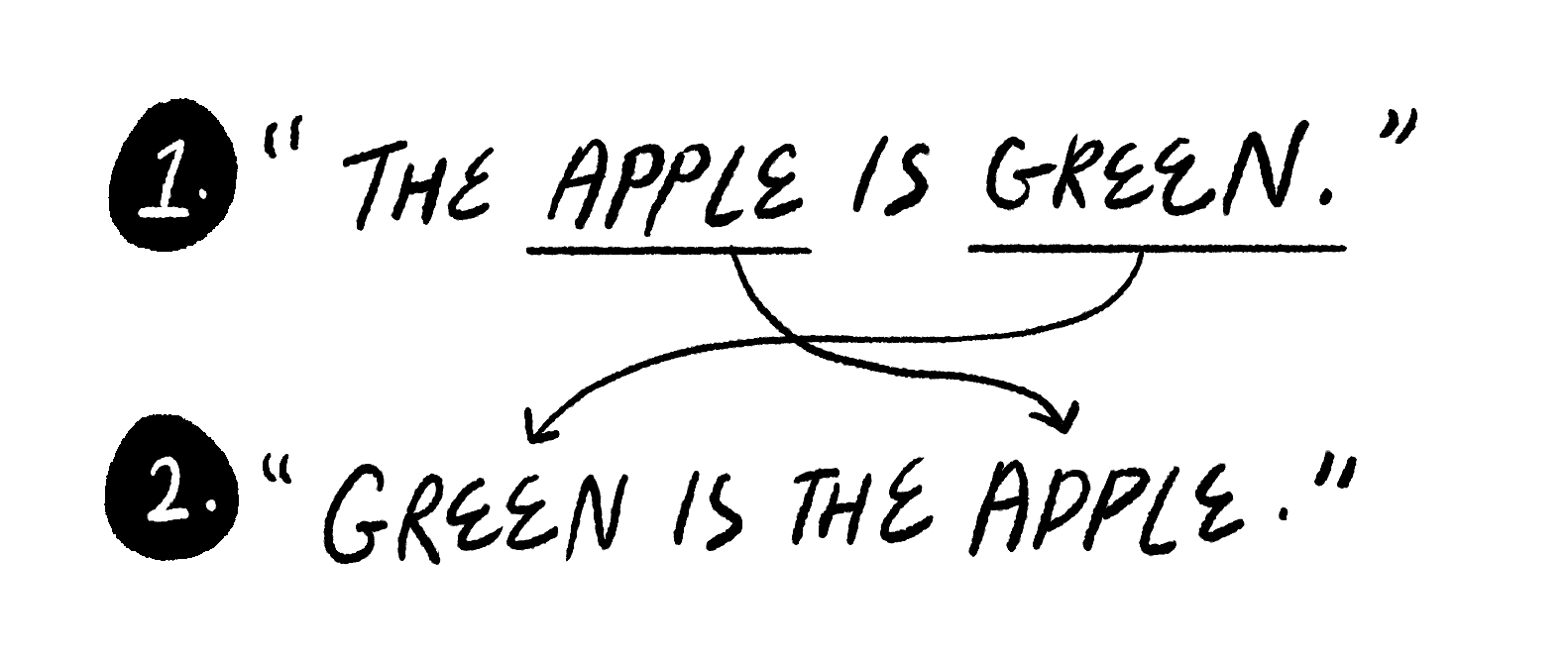

For example, in the book of Deuteronomy, the phrase “qeshēh ͑ōref”, and its variations, appears a few times (Deuteronomy 9:6, 9:13, 10:16, 31:27). As we can see, in some English translations, the word is directly translated into “stiff-necked”.

However, other English translations opt for the word “stubborn”. When the word “stubborn” is used, it obscures the image behind the idiom “stiff-necked”.

Commentaries have pointed out that the word originated from an ox that refused to do its master’s bidding. The master would place the yoke on the ox’s neck as the neck was perceived to be the source of power of the ox.

Knowing the origins of “stiff-necked” and its context allows us to appreciate that the phrase carries nuances of being “defiant” or “disobedient”. “Stubborn” does not begin to capture the essence of what is being said.

This little example shows how we can better understand the text we are reading when we are armed with knowledge of biblical Hebrew or Greek.

To better illustrate the beauty of learning the biblical languages, Dr Yee shares an analogy of a television (TV).

Many years ago, the TV started with black and white images and it did not have any audio. As technology progressed, the TV started to have colour and sound. Nowadays, there are even high-definition options.

Biblical languages are similar to that.

… learning the biblical languages helps open our eyes to God’s Word more vividly. However, it does not mean learning the biblical languages is mandatory for the layman Christian.

When we watch black and white TV with no sound, we are still able to follow along with the plot.

But with modern TV, we can watch shows with much more clarity. We see colours, shades and details and we even hear better. It makes the entire show come to life.

Thus, learning the biblical languages helps open our eyes to God’s Word more vividly. However, it does not mean learning the biblical languages is mandatory for the layman Christian.

The availability of translations is one of the beauties of Scripture. All over the world today, people do not necessarily need to know the original languages to have access to God’s Word.

The finer shade and nuances of the Bible fall on the shoulders of preachers, teachers and pastors. That’s why they go to seminary and are equipped to cover the pulpit – to explain nuances that everyday Christians may not be able to capture in a translation of the Bible, by virtue of the fact that it is a translation.

Two warnings

However, attempting to learn the biblical languages is not a walk in the park and Dr Yee has two points of caution.

1. The danger of thinking you know a lot

Students at seminaries take about 400 hours to be trained in one biblical language, which is equivalent to about three semesters (14 weeks each) of instruction.

Even with all that schooling, it does not make someone an expert in biblical languages.

It is dangerous to know a little but think you know a lot, says Dr Yee.

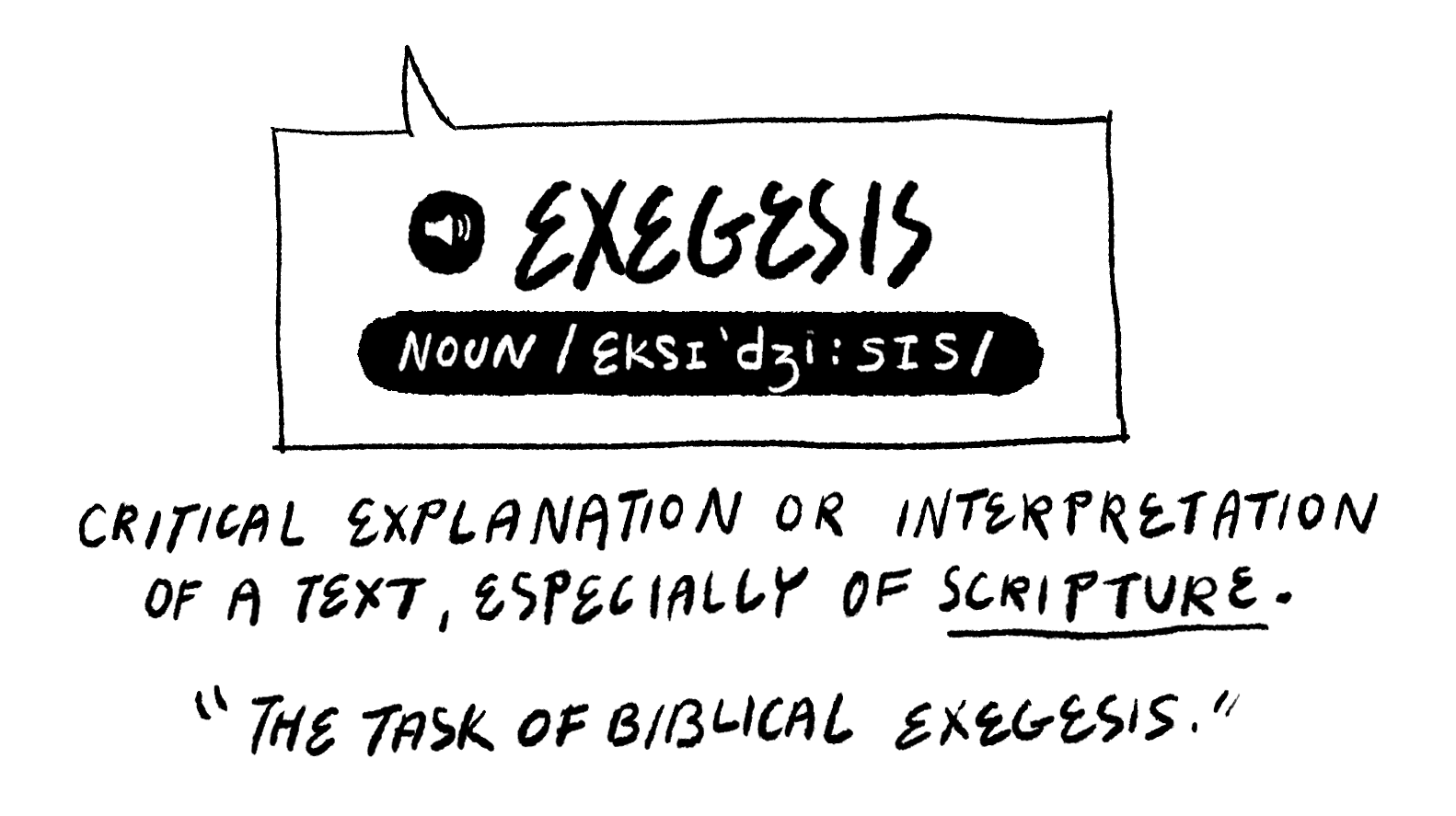

Though we might have an idea of some Greek or Hebrew words, we may not necessarily be equipped to exegete or know what the Bible is saying just from that very basic understanding of the language.

More than that, language is just one aspect of biblical studies. To have a full picture of the Bible, one needs to have knowledge of the Bible as a whole and of its historical-cultural backgrounds.

One also needs to know something about hermeneutics, which refers to the principles of interpretation. One also needs to know something about theology.

Only by putting all that together with the use of biblical language, would we then be able to have a better grasp of what the Bible is trying to say.

2. Our motivations for learning

It is also vital to set the learning of the biblical languages in the context of wanting to know God’s Word better, says Dr Yee.

Learning these languages is not merely an intellectual pursuit, though there is nothing wrong with having that as a motivation. However, our primary motivation when studying and putting in the hours of work should be to know God’s Word in greater depth.

We ought to set the learning of biblical Greek and Hebrew in the context of our faith, which would help our learning be more sustainable and pleasing to God.

How can we study the biblical languages?

With that settled, you might be wondering about ways to get started on your journey of learning these languages. The barrier to entry might seem high, but there are actually a wealth of resources for us to tap into.

Dr Yee recommends a classroom setting with a regular curriculum by enrolling into an accredited course.

Dr Yee explains that when you try to pick up any foreign language, you must deal with a different linguistic system. The morphology itself is a challenge for most students, as simply mastering the alphabet and being able to pronounce and put words together in a sentence can be difficult.

With quizzes and an instructor, you will be able to clarify your understanding of the material and have a better grasp of the language.

Moreover, a classroom setting provides you with a community of believers. This group of like-minded people can spur and encourage each other.

There are ad-hoc courses that pop up from time to time by different organisations.

Bible colleges in Singapore also offer opportunities to study biblical languages, such as Trinity Theological College’s Master of Theological Studies.

However, do note that Bible colleges and seminaries tend to require greater commitment and are usually for those looking to enter full-time ministry.

If a physical course is not your cup of tea, there are also many online courses readily available on the web. Here are some you might check out:

- Daily Dose of Greek

- Daily Dose of Hebrew

- Alpha with Angela (Greek)

- Aleph with Beth (Hebrew)

That’s not an exhaustive list and there are many more resources available — just look for a good, exercising wisdom and discernment.

Dr Yee suggests shortlisting some online options and checking with someone who is theologically trained, such as a pastor, on how reliable and competent that online course is.

This ensures that you can be properly guided in learning the biblical languages even if you choose to learn in your own time and pace.

All in all, whether one feels convicted to learn biblical Hebrew and Greek or not is a matter between you and God alone.

There is no hard and fast rule that says layman Christians must acquire such knowledge. However, if you feel called to study biblical Hebrew or Greek, consider it prayerfully and consult your mentors and leaders.

To all those on your journey of studying these languages, hold fast and press on! Don’t feel discouraged when the material gets difficult. Your efforts will reap good fruit in time to come!