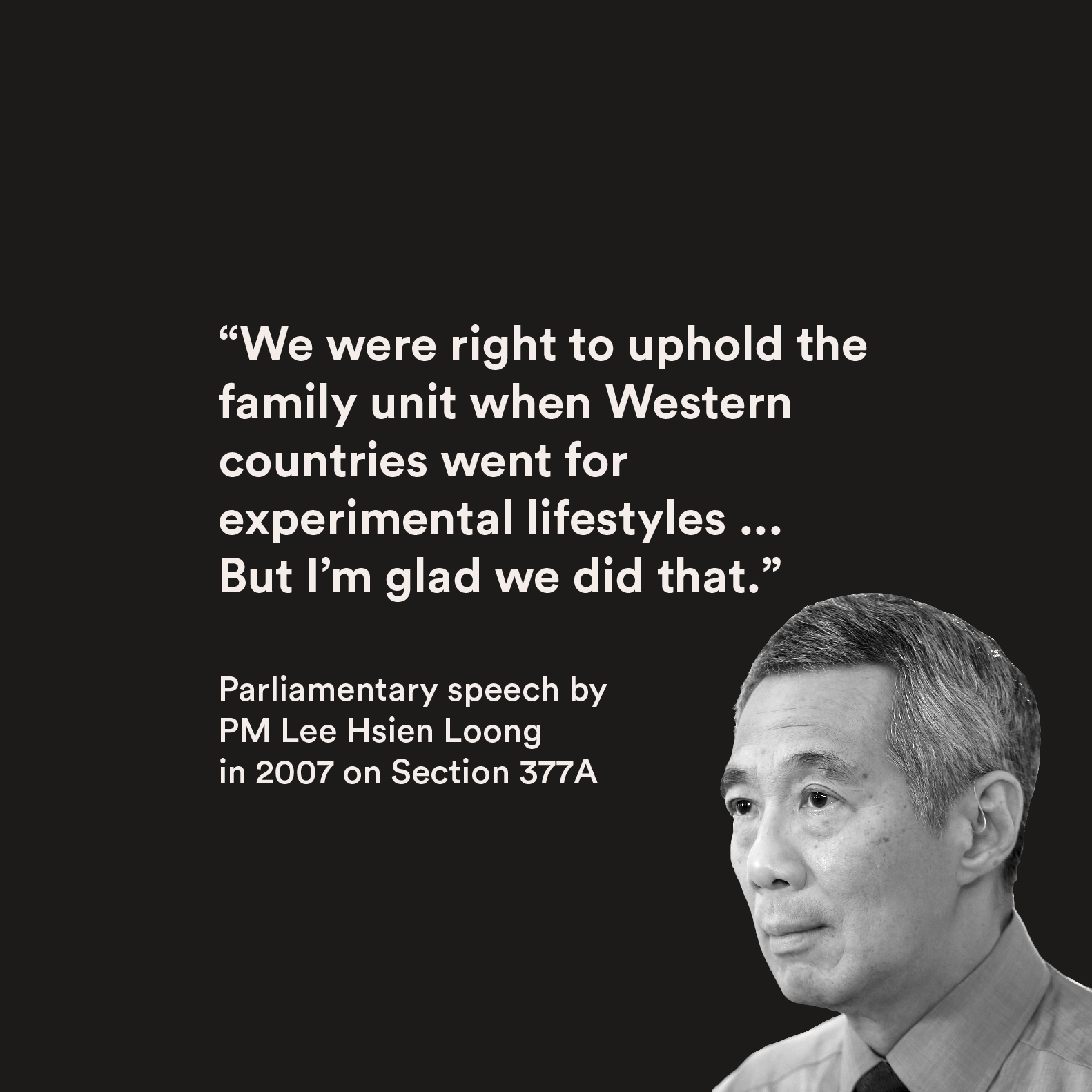

“Before we are carried away by what other societies do, I think it’s wiser for us to observe the impact of radical departures from traditional norms on early movers,” said Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong on the possibility of repealing Section 377A of the Penal Code in Parliament in 2007. The decision, just over a decade ago, was that there would be no change to the status quo.

Last year, in an interview on BBC HARDTalk, Mr Lee reiterated his stance. “This is a society which is not that liberal on these matters. Attitudes have changed, but I believe if you have a referendum on the issue today, 377A would stand,” he said.

“This is an uneasy compromise, I’m prepared to live with it until social attitudes change.”

The debate was revived following the recent ruling by India’s Supreme Court to remove Section 377A from the Indian Penal Code. Singapore Minister for Law and Home Affairs K Shanmugam said on Sept 7 that Singaporeans will ultimately determine whether Singapore does the same.

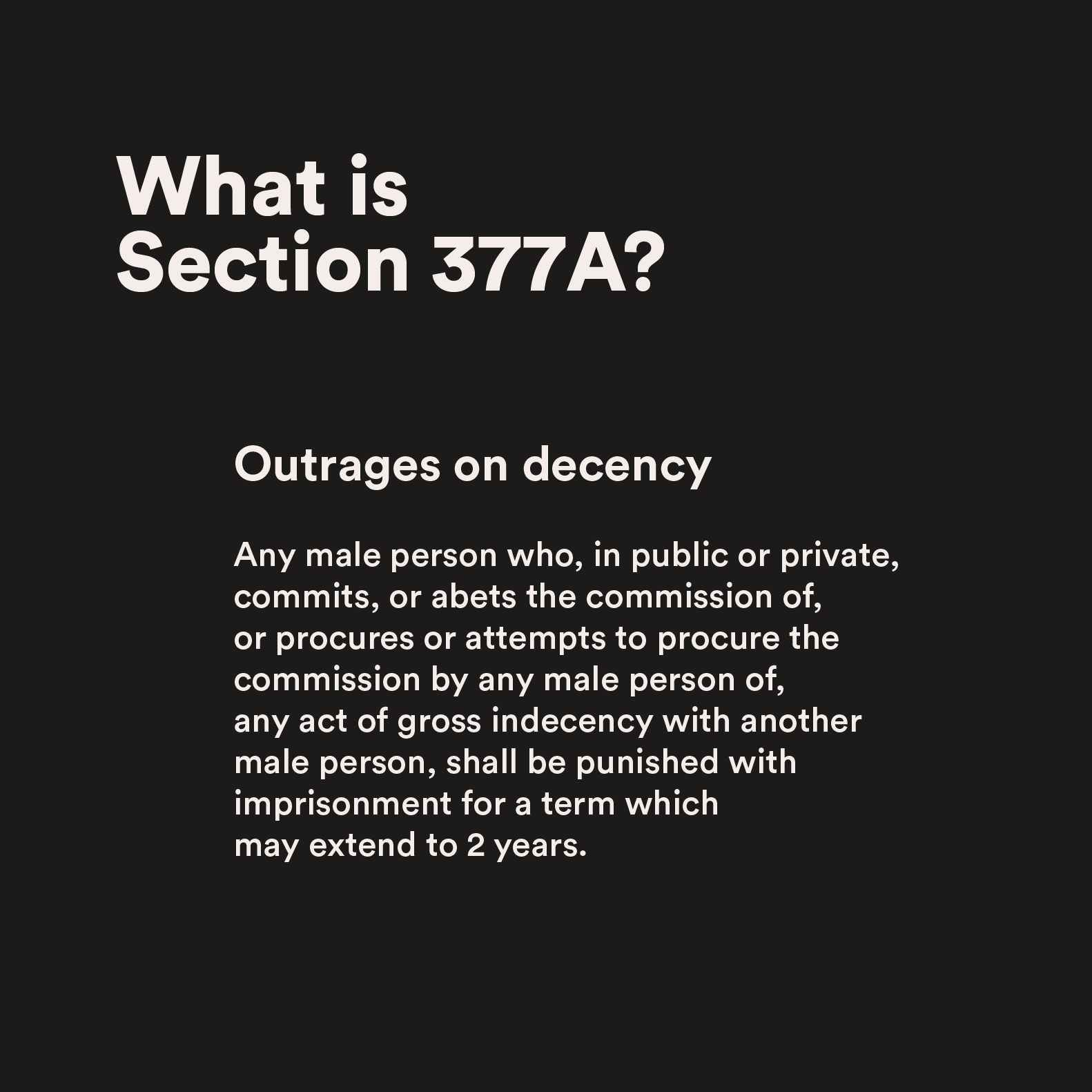

WHAT IS SECTION 377A?

Section 377A of the Penal Code states that “any male person who, in public or private, commits, or abets the commission of, or procures or attempts to procure the commission by any male person of, any act of gross indecency with another male person, shall be punished with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 2 years”.

To give this its full context, we first need to understand its parent statute, Section 377 of the Penal Code. In essence, Section 377 of the Penal Code spells out laws on sexual conduct, criminalising sex against the order of nature.

Under this law, “whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animals, shall be punished with imprisonment for life, or with imprisonment for a term which may extend to 10 years, and shall also be liable to fine”.

Section 377A zooms in specifically on sex between men, stating that it is an act of indecency – even if it is between two consenting males.

This law was first drafted by Thomas Macaulay, a member of the British Council, in the 19th century and was modelled on laws formed in the 1500s which defined unnatural sexual acts against the will of God and man. Consequently, anal penetration, bestiality and homosexuality were criminalised.

Singapore inherited this law as a British colony – as did other colonies including India, Malaysia and Myanmar. Other Asian societies never colonised by the British, such as Japan, China and Taiwan, do not have the same law on their books.

However, no less than the Prime Minister of Singapore has gone on record as saying that while the law exists, it is not enforced in reality.

WHAT ARE THE ARGUMENTS MADE IN FAVOUR OF THE REPEAL OF SECTION 377A?

Is 377A a regressive law that societies have outgrown? Former British colonies such as New Zealand and Australia – and even the United Kingdom itself – seem to think so, having overruled the statute and institutionalising gay marriage.

In Singapore, a man charged with having oral sex with another man in public filed a challenged against the statute in 2010. In a subsequent case heard by the Supreme Court, a gay couple contended that the Section 377A infringed upon their right to equal protection under the law, and “violated their right to life and liberty”.

However, their cases were dismissed by the High Court in 2013, and by the apex Court of Appeals the following year.

“Even if it is not actively enforced, the law still punishes our gay friends and relatives by signalling that what they do, and who they are, is condemnable and wrong,” argue the authors of a petition to repeal 377A, published this week.

WHAT ARE THE ARGUMENTS AGAINST THE REPEAL OF SECTION 377A?

Homosexual transmissions, in particular between men, still account for more than half of HIV infections in Singapore, as compared to the 36% of cases transmitted via heterosexual intercourse, even though the homosexual and bisexual population are a minority in the population. That’s the health argument.

Some also warn of a “slippery slope” should key moral laws be removed. In this argument, Section 377A is viewed beyond those it specifically implicates or incriminates, and stands instead as a symbol of a moral floodgate.

According to this viewpoint, the abolition of 377A would remove any moral argument allowing society to legislate against other forms of unnatural sex, such as paedophilia or bestiality. Moral lines must be drawn and not so easily abolished.

Ultimately, those arguing to keep the statute say the law should reflect the norms of society – rather than allowing a minority viewpoint to influence the majority. Singapore is still largely a conservative society standing on the pillars of traditional family values.

SO WHAT DO SINGAPOREANS SAY ABOUT SECTION 377A?

Singapore has not had a national referendum on any issue since Independence in 1965, and it seems unlikely that we will ever have a full national vote on this one issue. It would prove too divisive for a nation so proud of our ability to get people of different viewpoints to co-exist.

Short of a referendum, there are unscientific but statistically-significant proxies to gauge public perspectives on 377A. Online petitions, for example.

At the point of writing, there are about 90,000 signatures petitioning to keep Penal Code 377A and 25,000 petitioning to repeal Penal Code 377A – a significant proportion in favour of keeping the statute.

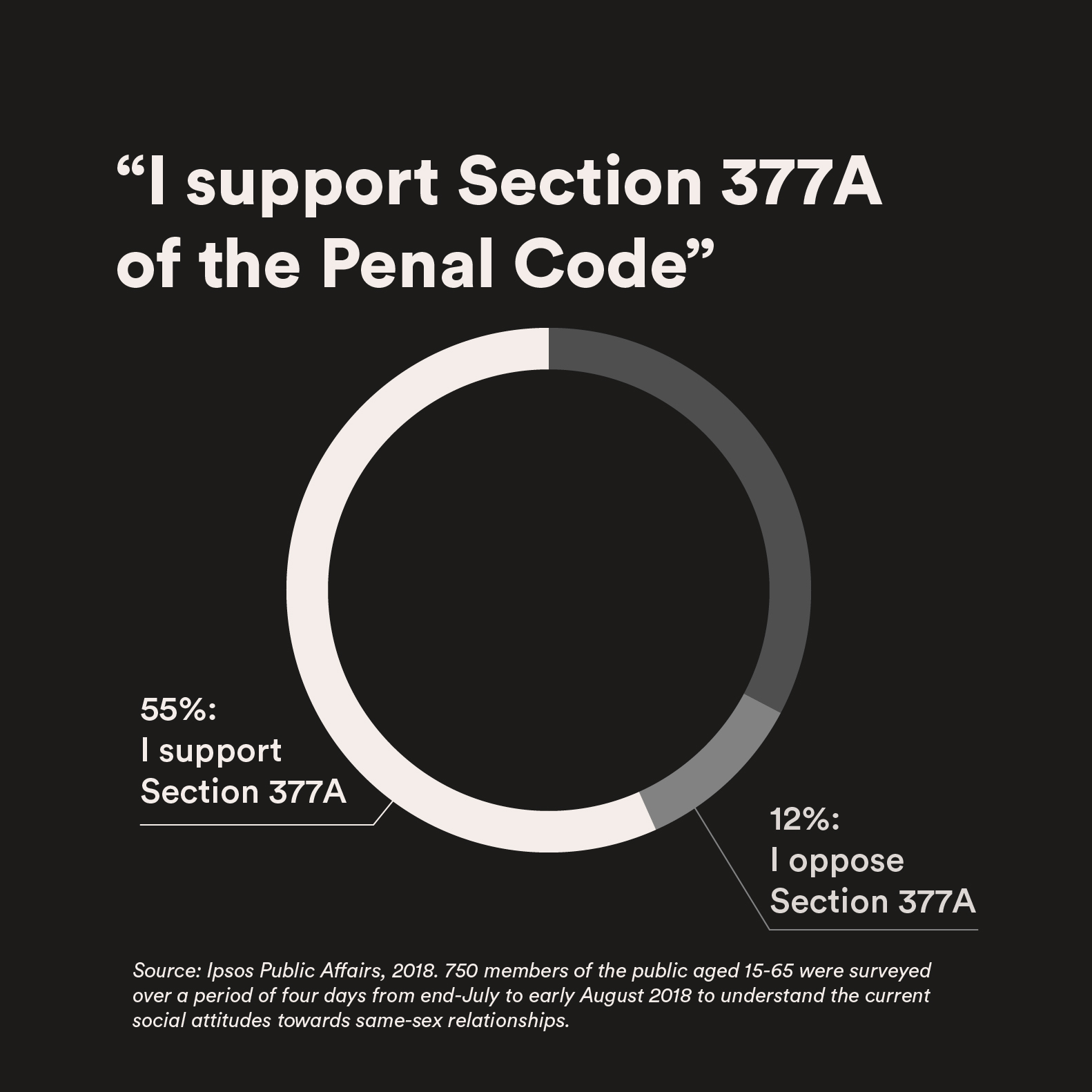

The Straits Times also published a recent survey done by Ipsos Public Affairs, an independent market research company, which showed a similar ratio of support: 55% of the respondents were reported to be supportive of 377A, while 12% said they opposed it.

By proxy, it appears that the majority of Singaporeans are still in favour of keeping Section 377A for now. But this landscape may change over time; the Ipsos survey found that Singaporeans aged 15-30 are more likely to oppose 377A than Singaporeans aged 55-65.

Whether the law remains or goes may be a battle that comes down to the next generation to determine.