Do you fear sharing about your faith in Jesus with a non-Christian? Do you fear speaking publicly about important issues from your perspective as a Christian?

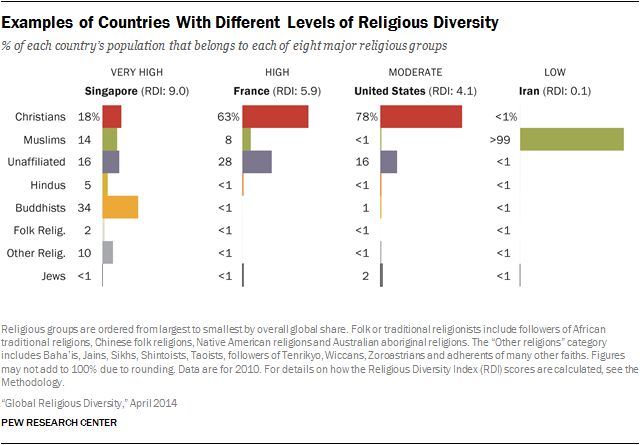

These are issues pertinent anywhere in the world, but they somehow seem amplified in Singapore, the country that regularly tops Pew’s Religious Diversity Index.

So what can Singapore Christians do or not do in practising and propagating their faith? While the boundaries are by no means clear, there are several key legal and quasi-legal principles and rules which form the framework to navigate this question. There have also been various examples which the Government has used to highlight clearer out-of-bounds markers.

This discussion sets out what I think the position is now, and not what I think it ought to be. We should also note that social-political conditions change over time; nothing is set in stone. With that, let’s consider the key principles and rules.

Article 15(1) of the Singapore Constitution states that every “person has the right to profess and practise his religion and to propagate it.” However, there can be laws relating to “public order, public health or morality” limiting this right, and indeed there are.

Article 14(1) of the Constitution states that “every citizen of Singapore has the right to freedom of speech and expression”. Parliament may enact laws to restrict this for national security, public order, morality, or for prohibiting defamation or incitement to offences (among other things).

In sum: A Christian can profess, practise and propagate your faith privately and publicly. You can evangelise to anyone. You can express worship to God. However, there are of course legal limits.

The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act (MRHA) empowers the Government to restrain (i) a religious leader, (ii) any person who is inciting, instigating or encouraging any religious group or religious institution or any religious leader to be, or (iii) any other person from:

- causing feelings of enmity, hatred, ill-will or hostility between different religious groups;

- carrying out activities to promote a political cause, or a cause of any political party while, or under the guise of, propagating or practising any religious belief;

- carrying out subversive activities under the guise of propagating or practising any religious belief; or

- exciting disaffection against the President or the Government while, or under the guise of, propagating or practising any religious belief.

The Internal Security Act (ISA) empowers the Government to detain any person to prevent him from acting in any manner prejudicial to Singapore’s security or the maintenance of public order or essential services.

The Sedition Act makes it an offence “to promote feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore”.

The Penal Code has further relevant offences. Section 298 prohibits anyone from deliberately “wounding the religious or racial feelings of any person” by speaking, making sounds, gesturing, placing any object in the sight of a person, or causing any matter to be seen or heard by a person.

Section 298A criminalises a person who “knowingly promotes or attempts to promote, on grounds of religion or race, disharmony or feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will between different religious or racial groups” by words, signs, visible representations or otherwise, or who knowingly does anything “prejudicial to the maintenance of harmony between different religious or racial groups and which disturbs or is likely to disturb the public tranquility”.

Finally, the Parliamentary debates on the above legislation and the MRHA White Paper set out further guidance on what the Government considers to be no-go boundaries in this area. I would point out that it is not clear whether “religion” in the above laws includes atheistic worldviews. While the Court has defined “religion” in another context to mean beliefs relating to God, it is not clear that definition applies to the above laws, especially since some strands of certain religions do not necessarily involve belief in God.

There have been various cases over the years which reveal how the Government applies the above principles and rules.

In the recent Amos Yee case (Public Prosecutor v Amos Yee Pang Sang, 2015; Decision ex temporare), the teenage video blogger was convicted under Section 298 of the Penal Code for the remarks in his video comparing Lee Kuan Yew with Jesus, saying “they are both power hungry and malicious, but deceive others into thinking that they are compassionate and kind. Their impact and legacy will ultimately not last as more and more people find out that they’re full of bull”.

The blogger called followers of both “completely delusional and ignorant and have absolutely no sound logic or knowledge about him that is grounded in reality”.

In the Chick Publication Tracts case (PP v Ong Kian Cheong, 2009), a Christian couple was charged under the Sedition Act (among other things) for distributing comic tracts published by Chick Publications which were deemed seditious and to have promoted feelings of ill-will between Christians and Muslims. Unfortunately, we do not know from the decision what exactly about these tracts were denigrating.

In the Andrew Kiong case (decision unreported, see Page 43 of Bias and religious truth-seeking in proselytisation restrictions), Kiong was convicted under Section 298A of the Penal Code for injuring religious feelings of another person by leaving envelope-sized cards on the windshields of cars that he believed belonged to those of another faith, which contained questions that were calculated to insult them.

In the 2005 Bloggers cases, three bloggers were convicted under the Sedition Act for posting online comments against other races (see Public Prosecutor v Benjamin Koh Song Huat, 2005; Public Prosecutor v Lim Yew Nicholas, 2005; Public Prosecutor v Gan Huai Shi, 2005, from Page 39 in Bias and religious truth-seeking in proselytisation restrictions; Page 120 of Kerstein steiner religion and politics in Singapore; and Page 219 of Maintaining Religious Harmony).

In the case of Benjamin Koh, he “spewed vulgarities, derided and mocked their customs and beliefs and profaned their religion”.

In the case concerning Pastor Rony Tan of Lighthouse Evangelism Church (see Page 44 of Bias and religious truth-seeking in proselytisation restrictions), the Internal Security Department (ISD) investigated video clips of Pastor Tan in his church service interviewing people who had converted to Christianity from other religions, a segment which led to laughter from the congregation. He also compared the efforts of someone from another religion to seek answers from his mentors as “the blind leading the blind”.

The Ministry of Home Affairs said in a statement that the comments were “highly inappropriate and unacceptable as they trivialised and insulted” others’ beliefs, which could give rise to tension and conflict between the faiths. ISD told Pastor Tan that in preaching or proselytising his faith, he must not run down other religions, and must be mindful of the sensitivities of other religions.

Eventually, the situation was defused after the clips were removed, and Pastor Tan made a public apology and personally visited the religious leaders of the other faiths.

In another ISD investigation concerning Pastor Mark Ng of New Creation Church, (see Page 46 of Bias and religious truth-seeking in proselytisation restrictions), a video was posted online by someone else (not the church) in which he can be heard joking with the congregation about traditional rituals; in one instance, he compared praying to the gods of other faiths to “seeking protection from secret society gangsters”.

He subsequently apologised and the church sought to have the video removed.

There have been reportedly three occasions when the Government considered invoking the MRHA: First, when a Muslim leader urged Muslims to vote for a Muslim candidate in a General Election; second, when a Christian pastor used his church publications and sermons to criticise Buddhism, Taoism and Catholicism; and third, when an Islamic religious leader condemned Hindu beliefs (Nirmala, Govt Reins in Religious Leaders, The Straits Times, May 12, 2001, cited in Kerstin Steiner, Religion and Politics in Singapore: Matters of National Identity and Security, A Case Study of the Muslim Minority in a Secular State, Osaka University Law Review 58 Pages 107 to 134; see Page 119 of Kerstein Steiner: Religion and Politics in Singapore).

Evangelism to anyone and everyone is clearly permitted by the Constitution. What the laws seek to prevent is “insensitive, aggressive religious proselytisation”. It is perfectly permissible to point out differences between one’s religion and another’s. The Penal Code criminalises speech which deliberately promotes ill-will between religions.

The Government has clarified that a person writing an article based on facts, notwithstanding that it may be racially or religiously sensitive, will not likely be caught; a critical but rational and objective discussion of religion and religious principles will also not likely be caught.

Similarly, a person may share his testimony of his conversion from one religion to another on the Internet, stating how he found fulfilment and meaning in life after he converted to the other religion, without denigrating another person’s religion (see Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs Assoc Prof Ho Peng Kee’s statements in the Parliamentary Debate on the Penal Code (Amendment) Bill).

But is an entirely different matter to denounce other religions in the process. (See the comments from Prof S Jayakumar, then Minister for Home Affairs, in Column 1050 of the Second Reading of the Religious Harmony Bill in 1990). So, for example, we should not say another religion is a “threat” or say that a particular person in another religion is “the anti-Christ” or suggest that some particular belief or practice of another religion is from the devil.

Or, in simple terms: You should promote your own faith without putting down any other faith.

Other examples cited as “insensitive or aggressive proselytisation” include (see the Annex to the MRHA white paper):

- Pasting posters or distributing Christian pamphlets about a Christian seminar at the entrance of a temple of another faith.

- Trying to convert students who felt depressed after failing their examination.

- Pamphlets describing the Pope as “Communist” and the “anti-Christ”.

One other example cited: Trying to convert critically-ill patients on their death beds without regard to their vulnerabilities or sensitivities of their relatives. This does not mean we cannot minister to people who are vulnerable. Indeed, all the more when they are in need, we should meet them where they are and be with them!

The point is that where there are sensitivities and vulnerabilities, we should minister, and not attempt to convert, especially where the person has no desire to be converted.

But if the person is then interested to hear your views, you are free to share, preach, and lead the person to faith (see Assoc Prof Ho Peng Kee’s comments in the 2007 Parliamentary Debate on the Penal Code (Amendment) Bill).

While the MRHA is intended to prevent the conflation of religion and politics, this does not mean that religious leaders cannot participate in politics, campaign for or against the Government or any political party, or be involved in any action relating to public policy.

What it means is that they must do so in their capacity as individual citizens and not as religious leaders (see Parliamentary Debate on the Maintenance of Religious Harmony Bill and the MRHA white paper, paragraph 22). Indeed, there are and have been elders of churches who have held political offices.

What is clearly a no-go, however, would be to use one’s religious office to push for or against a political candidate solely based on religion.

Examples of instances where the Government has deemed that religion was used for political purposes include:

- Preaching in a sermon that the political climate is oppressive;

- Declaring in a sermon that certain politicians, judges and ISD officers would face God’s punishment for detaining those involved in the alleged Marxist Conspiracy;

- Urging workers in a sermon to stand up for their rights to press for wage increases and to vote “with their eyes wide open” in the General Election.

Further, the Government has stated that it is “neither possible nor desirable to compartmentalise completely the minds of voters into secular and religious halves, and ensure that only the secular mind influences his voting behaviour” (MRHA white paper, paragraph 24) It is an explicit statement that people vote and make political decisions based on both religious grounds and non-religious grounds.

So both Scripture and law accept that our religious and ethical values should be considered when participating in the democratic processes as citizens.

Yet, does this mean that religious leaders cannot teach on issues which are matters of public policy? Not at all. Given how extensive legislation and policies are in touching various aspects of our private and public lives, if that were the case, then religious leaders would not be able to teach on almost anything!

Instead, the Government has made clear that religious leaders can teach on issues regarding ethics and conscience such as abortion (MRHA white paper, paragraph 26a).

The Government also recognises that religious or ethical beliefs have political and social implications, and its intent is not to determine whether such beliefs are right or wrong (MRHA white paper, paragraph 27).

I end with the questions I started with: Do you fear sharing about your faith in Jesus with a non-Christian? Do you fear speaking publicly about important issues from your perspective as a Christian?

I once feared all this. Yet God’s Word compels me to do it. And the laws of Singapore permit me to – to the extent that I speak about my faith sensitively, winsomely and without denigrating other religions. So what have I to fear but the tyranny of criticism?

Have you seen and heard the work of God in your life? If so, you can be like Peter and John who declare in Acts 4:20, “We cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard.”

As a Christian who is also a lawyer, Ronald JJ Wong believes in access to justice for all. Burdened for the common good of society, he advocates for the marginalised and volunteers pro bono for the less privileged.