The year was 2000.

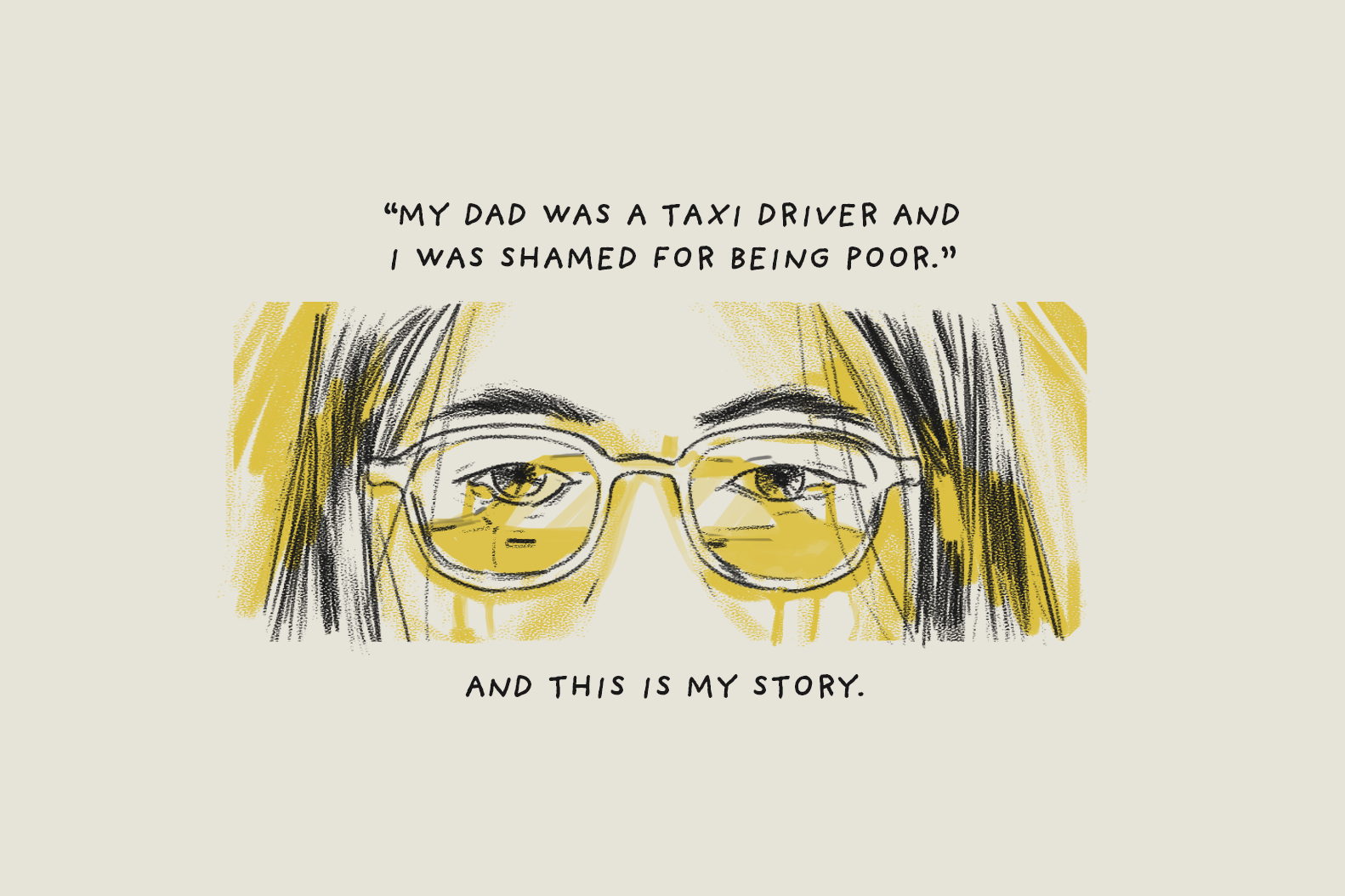

I was enrolling into primary school, and my father had just obtained his taxi driver’s vocational licence some three years after the Asian Financial Crisis.

After multiple failed attempts to keep his business afloat, my dad decided that the only way to sustain us was to become a taxi driver.

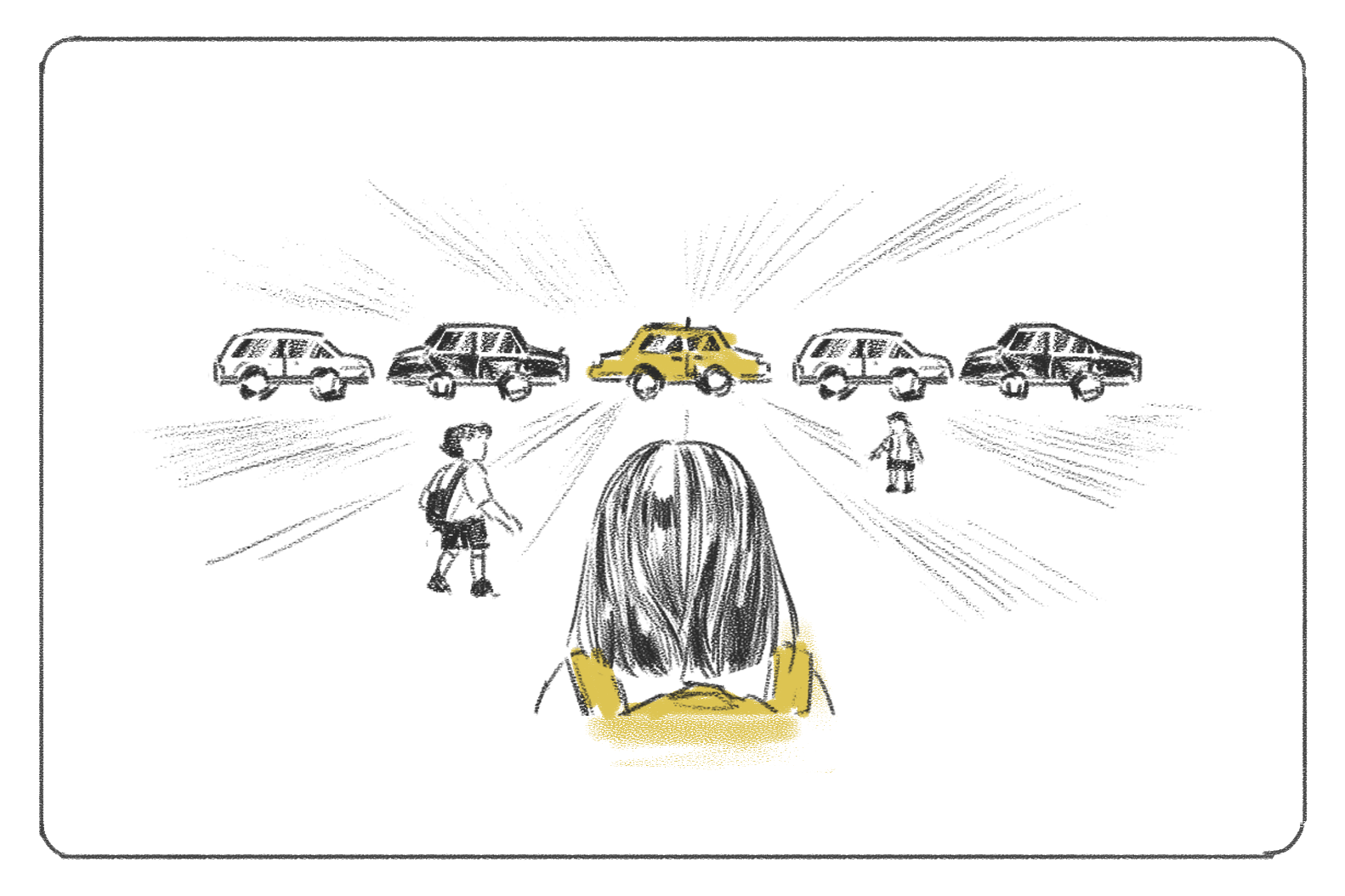

And so a day came when my mother brought me downstairs – my father wanted to show us his yellow taxi.

I didn’t like it at all.

Classmates would pass notes around talking about my parents, and they would call me “taxi” whenever they walked past me.

The lethal fragrance of pandan leaves mixed with Ambi Pur gave me a headache. There were wooden beaded seat pads that looked uncomfortable to sit on. The bright yellow colour screamed “taxi” from a mile away.

I didn’t like it, but out of courtesy to my parents I decided to keep quiet.

My parents agreed that my father would pick me up from school since he drove the night shift. I wasn’t exactly pleased about sitting in the heavily-scented taxi, but I kept quiet about it.

Every day after school my dad’s taxi would stand out among the throngs of cars lined up outside the school.

It was so yellow, it hurt.

In the beginning it was only weird looks. But my friends were not the best at keeping inappropriate comments to themselves (they were seven years old, to be fair), and soon I started getting questions and comments.

- “Your dad is a taxi uncle?”

- “My dad said that taxi uncles are poor.”

- “My mum told me that if I don’t study hard, I will become a taxi driver.”

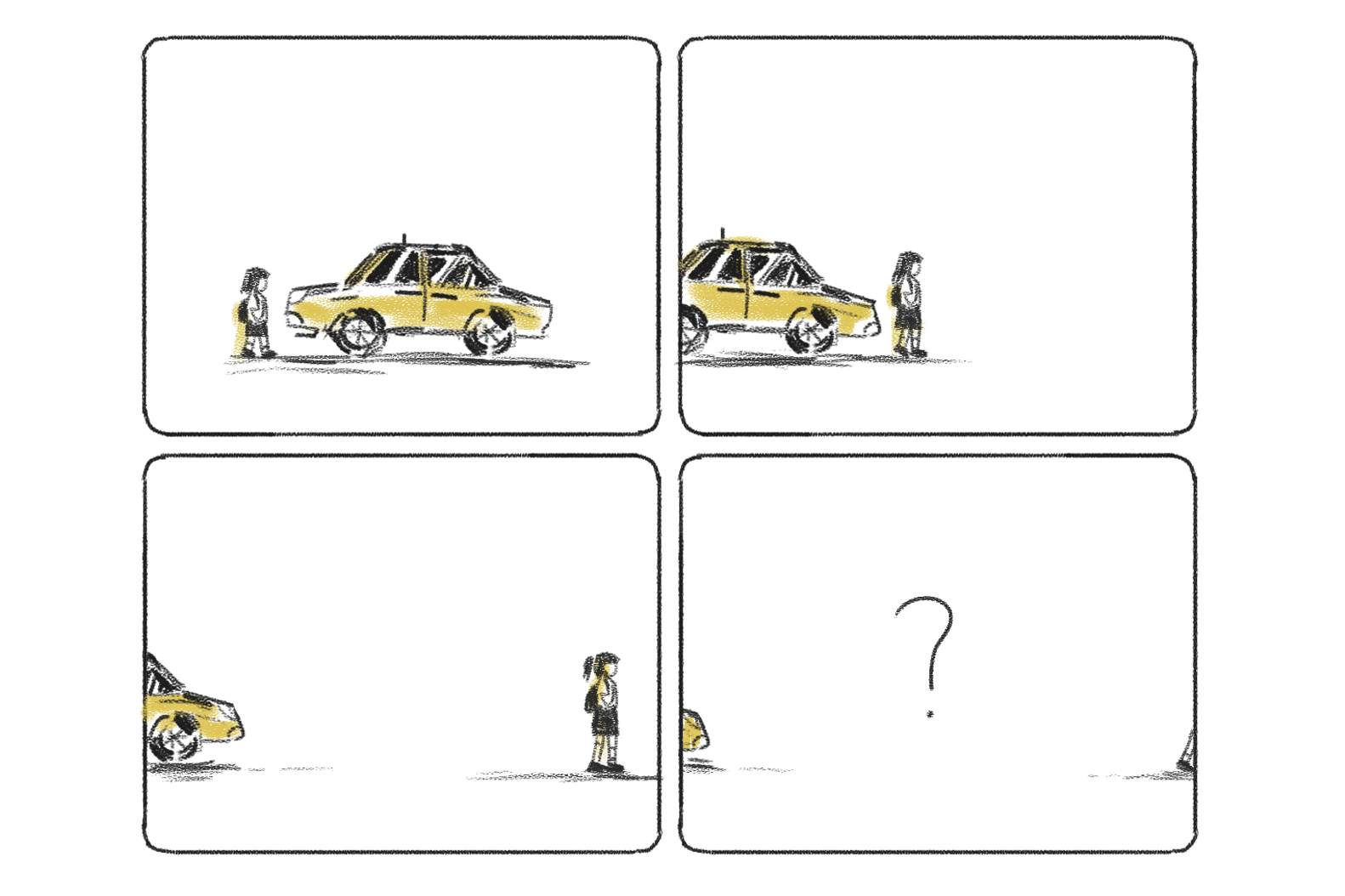

I was seven and I didn’t know how to respond to such comments, so I eventually told my father to wait for me at the nearest HDB carpark instead.

He didn’t ask, but I think he knew why. Some months later, I told him to stop picking me up altogether.

Over the years, my dad never said anything to me about his occupation. My mum, on the other hand, had a bone to pick with my attitude.

“Why are you acting up like this? Your dad didn’t commit a crime, what is there to be so ashamed about?” she would chide me.

Of course, she didn’t know that I was being bullied in school for being poor. I was picked on for being the taxi uncle’s daughter.

I remember a time someone invited me to her house – an apartment in an upscale estate, complete with a private lift.

She introduced me to her father as her “poor classmate”. “Her father is a taxi uncle,” she said.

They had a good laugh about me and my family. And as usual, I kept quiet. These incidents kept repeating for the bulk of my primary and secondary school years — rich kids in their perfect families having a good laugh at me.

Classmates would pass notes around talking about my parents, and they would call me “taxi” whenever they walked past me.

Every time we returned to school after the holidays, our teachers would ask everyone to share about where they went for their holidays.

Some would say Disneyland, USA, Japan, Taiwan… Those who said Indonesia or Malaysia would get a few sniggers.

I always said nothing but still got laughed at.

Throughout my school years, school trips were a luxury we couldn’t afford.

A trip to Perth to experience the farms when I was 11. A cultural exchange trip to Chongqing when I was 14. A choir competition in the Czech Republic when I was 17. University exchange program when I was 21.

I had never gone on any of those things.

“I heard her family is super poor, that’s why she’s not going. Do you know her dad drives a taxi? These people only work hard at acting pitiful.”

A friend had said these words behind my back.

But by then, I had already internalised “poor” as part of my identity.

A few years later, Korean singer Zion.T released Yanghwa BRDG.

That’s a song about his father, who as a taxi driver always rode on the Yanghwa Bridge to make ends meet for his family. As bizarre as it sounds, that was when I cried to a hip hop song for the first time:

I was always alone at home

My dad was a taxi driver

Whenever I asked him where he was

He’d answer, Yanghwa Bridge

Every morning, he’d leave me

Candy and ramen

My dad would end his shifts at dawn

Waiting to fill his pockets

A taxi driver’s life is not easy indeed; ever since my father became one, we’ve never had a proper reunion dinner together.

Chinese New Year Eve is one of the best business days in the calendar for a driver. He would spend the entire day outside picking up passengers and ferrying them to their reunion dinners, only to return home at dawn.

My father worked hard to pick our family up again financially. But in the world’s eyes, we were still poor. As a child back then, the concept of reunion dinners was a luxury.

It wasn’t even about the food on the table, but the glaring fact that others could dine together while we could not.

Many years later, a friend made a casual remark to me while we were out overseas.

I was thinking of buying something that my mother would’ve really liked, when something the person said made me stop in my tracks.

“You never travel before ah?” she said. “I feel like you’re just buying random things for no reason.”

I think my friend meant no harm, but the emotion I felt in that moment was pure shame.

Shame of being that poor kid. Shame of having parents who worked their lives away without a break. Shame of being that family who has never had the opportunity to travel together. Shame of accidentally exposing my suaku (aka country bumpkin) side. Shame of being so easily excited by what the others thought were “cheap” things.

I spent the next few days feeling torched by that comment. Every time I recalled that moment, I felt so embarrassed.

I rationalised that to my friend, it might have looked like impulsive spending. Or maybe even panic buying. Maybe that friend was just keeping a lookout for my finances. Or maybe that friend was just concerned about how I was going to be able to pack my luggage.

But well-intentioned or not, that comment exposed years of buried shame I’ve tried so hard to ignore and forget.

My mother’s lecture about my attitude towards my father’s yellow taxi came back to me again.

What was I so ashamed of?

A few days ago, Singaporean TikTok user Zohtaco posted a video about her first luxury bag – a SGD$79.90 Charles & Keith bag gifted by her father.

What started from a girl’s plain excitement at getting a new bag soon turned into an ugly furore of buzzkill comments calling her out for her use of the word “luxury”.

In a response video to the comments, Zoe explained that her family came from a humble background and they didn’t have a lot when she was growing up.

“We couldn’t buy new things as simple as bread from BreadTalk… That kind of thing was such a luxury to us,” she said, on the verge of the tears.

“Your comment spoke volumes on how ignorant you seem because of your wealth. To you an $80 bag may not be a luxury. For me and my family it is a lot. And I’m so grateful that my dad was able to get me one. He worked so hard for that.”

To me, Zoe’s story spoke volumes about our country’s wealth culture.

I was reminded of all the remarks made from privilege that I received over the years.

I was a taxi driver’s kid, just like how my peers were a doctor’s kid, a businessman’s kid, a teacher’s kid… But who our parents were was the very thing that tore us apart.

I was expected to play the role of the poor kid in society’s script. Be pitiful. Have very little. Look yearningly while others indulge. Don’t gloat about anything. Stay in my lane.

A poor kid like me should know better than to show any interest in products of better quality, or brands above a certain price range. Don’t use rich people vocabulary like “luxury” or “bougie” on myself or my belongings.

But how much is truly enough? How expensive must it be for it to count?

In Netflix’s current top K-drama offering The Glory, main character Moon Dong-eun, played by Song Hye-kyo, is a bright and hopeful girl who nurtures dreams of being an architect.

However, she becomes the target of the school’s gang of bullies made up of kids from prestigious, influential and rich families. The bullies’ only motive is boredom and they walk away scot-free from their crimes.

Dong-eun meanwhile grows up to become an extremely cynical adult. The smile has left her face – the harsh reality of being underprivileged has scarred her through and through. An innocent passing remark by a friend from a well-to-do background ended up bringing up her past hurts.

“Your childhood must have been like a box of chocolates. Now you’ve grown up to be a good, happy adult. You say something so naive, yet you have no trouble living your life,” Dong-eun says in response.

We are not held accountable for the words we say that more often than not, inflict wounds on others.

He meant no harm, but to Dong-eun his words reeked of privilege.

It’s easy for us to speak carelessly these days; my colleague calls it a “physical manifestation of leaving a comment online and disappearing”.

Indeed, we laugh at Zoe’s luxury bag because we are privileged enough to own something more high-end than that. We jeer at kids from humble backgrounds because they make us look better off.

We make comments about people’s spending patterns and dream purchases because we seldom stop to consider their story.

We are not held accountable for the words we say that more often than not, inflict wounds on others.

So back to my father’s yellow taxi. In 2019, he suffered a stroke and was forced to retire prematurely.

I should’ve felt a wave of relief – finally, good riddance to the yellow taxi. But I didn’t.

My father’s yellow taxi was a symbol of provision for our family.

It was his safe shelter on stormy nights when he was out driving. It was the vehicle that ferried his child whom he had optimistic aspirations for. It was our family’s personal ambulance as I was rushed to the hospital in the middle of the night.

It was a sign of his hard work and perseverance in the face of the harshest adversities. It was part of his identity.

For as long as I can remember, my father may only have had his yellow taxi. It was all he had, but it was enough.

Enough to keep us afloat. Enough to see me through to adulthood. Enough to sustain us through multiple medical emergencies. Enough for us to finally have a reunion dinner together.

And I’m sorry that I didn’t see that earlier.

- Have you ever faced discrimination like the author of the article?

- Have you released forgiveness? What might healing look like for you?

- What does the Word of God say about how we should treat one another (whether we are rich or poor)?

- What does having more empathy in our conversations look like?