Children are pure and innocent… right?

Unless we are talking about the kids in the latest Netflix drama, Juvenile Justice, which is currently sitting at No. 1 in Singapore’s top 10 list.

Released on February 25, the show revolves around South Korea’s juvenile court where offenders are still considered minors and cannot be charged criminally.

We journey with Judges Cha Tae Joo and Sim Eun Seok – played by Kim Moo Yul (Space Sweepers) and Kim Hye Soo (Dr Romantic, Signal) respectively – as they tackle complex cases while trying to balance meting out sentences that are both just yet merciful.

Juvenile Justice may not have received much promotion, but it didn’t need to. While I hadn’t been planning to watch the show, my social media feed was buzzing about it.

And for good reason. The concept of misguided youths committing heinous crimes is unthinkable. We are talking about shocking cases such as murder, gang rape, prostitution and the likes here.

Sadly, they aren’t completely fictitious. Perhaps it is this reason that the show is so riveting – it highlights the reality of our society and challenges the notion that not every child is as innocent as they seem.

And most importantly, it forces us to wonder: How exactly did the kids end up becoming delinquents?

The role of the family in misconducts

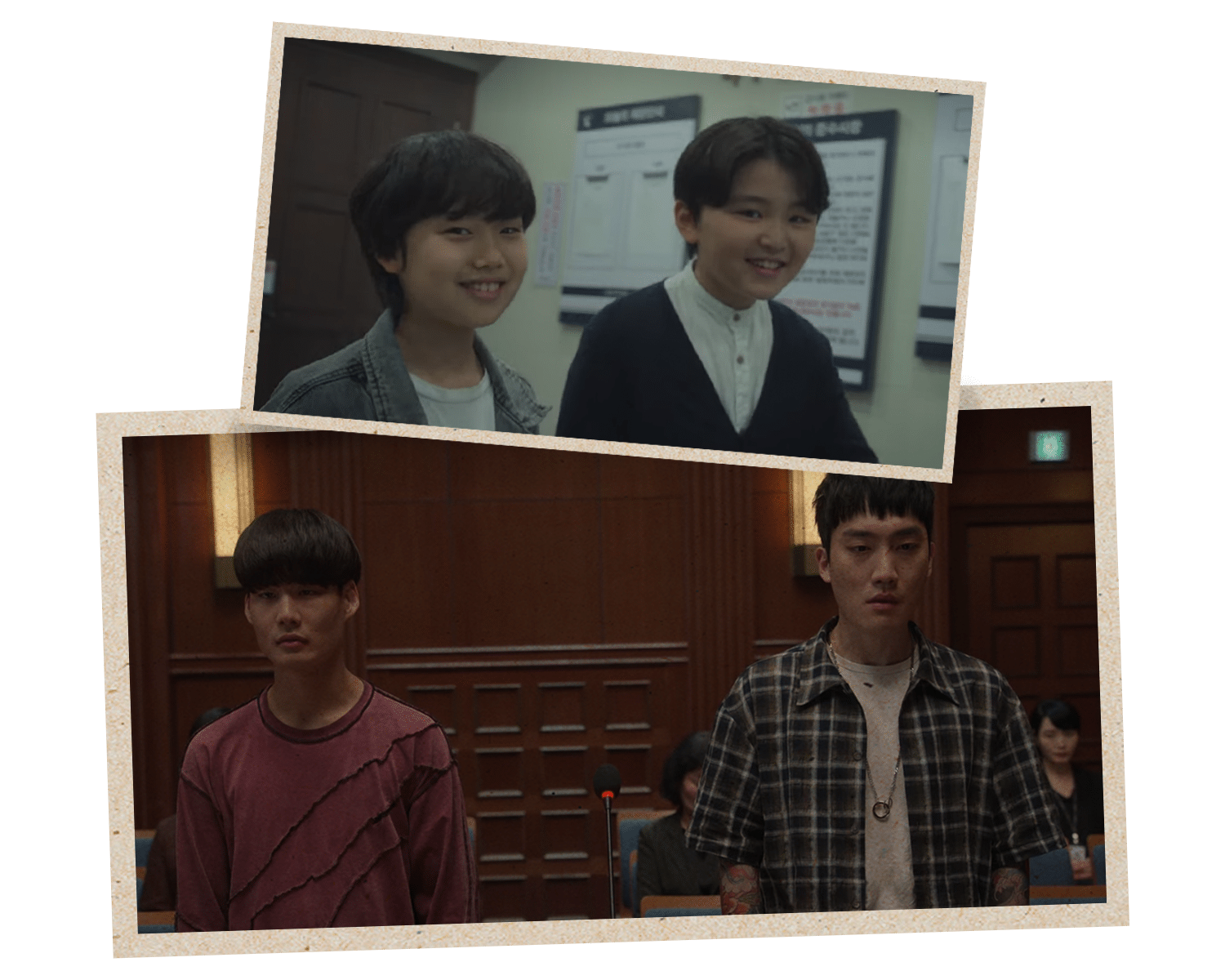

The first case that the show opened with was a murder crime.

Turning himself in for kidnapping, killing and mutilating an eight-year-old boy, 13-year-old Baek Seong U would only face a maximum of two years in a reformatory centre under the Juvenile Act.

But as the plot thickens, we find out that there’s actually another mastermind behind this crime – 16-year-old Han Ye Eun.

Han was the one who killed the boy and enlisted Baek’s help because unlike him, she was over the age of 14 and would face criminal charges if caught.

“Both of us don’t have to go to jail,” Han plotted. “Both of us can get away with this.”

But of course, they were exposed and Baek and Han were sentenced to two years in the juvenile reformatory centre and 20 years in jail respectively.

At the end of the hearing, the two judges of the trial discussed the future of the two kids and pondered if a prison sentence was really the best outcome for Han.

“I’m just worried,” Judge Cha commented. “She will serve her sentence and grow into an adult. What happens after that?”

One of the main themes of Juvenile Justice is the contention between using the law to punish and using it to rehabilitate. This is best exemplified by the two main characters.

Judge Cha symbolises mercy. As someone who has been in the system before, he knows the power of rehabilitation and always believes the best of the discharged juveniles under his care.

“Everyone criticises juvenile offenders. It’s only us judges who can give them a second chance,” he said.

On the other hand, Judge Sim represents justice. She doesn’t believe in leniency as it is her conviction that everyone should be held accountable for their actions.

Circling back to Judge Cha’s question, Judge Sim acknowledged the limits of the law.

“Even though we’re judges, we can’t change who she is inside,” she replied. “That’s up to her parents. If only they could make her realise how serious her crime is. But that won’t happen.”

The viewers are then reminded of Han’s parents’ apathy throughout the whole hearing process.

“She committed such a heinous crime, but her parents didn’t even attend the trial,” said Judge Sim. “If the parents don’t make an effort, the children will never change.”

Hurting people hurt others

The subsequent cases also drummed in the importance of parental care and guidance.

This article will be way too long if I elaborate on every single case so I won’t be going into the details. But it is clear that be it abuse, negligence or overprotection, family upbringing is often the reason why juveniles become offenders.

Years of research have also pointed to a significant link between adverse childhood experiences and delinquency (1, 2, 3). Many offenders were once victims themselves.

As summed up by one of the characters: When children act out, it is because they want their families to know that they are hurting too.

That isn’t to say that family is the only factor — society plays an integral role too.

In one of the later episodes, viewers are introduced to offenders who “graduated” from the crimes of their childhood to commit even more diabolical offences because they got off lightly the first time.

What did they learn? Judge Sim angrily pointed out. That the law doesn’t protect all victims.

“Neither their families nor their schools made them realise the seriousness of their crimes. Then at least the court should have scolded them and taught them!” she raged.

Later, she emphasised that if it takes an entire village to raise a child, then a child’s life could be ruined if the entire village neglects him.

“No one has the right to criticise them. Everyone is a perpetrator.”

People deserve a second chance

Having completed the series, what I took away most was the necessity of both justice and mercy.

These days, social justice is a buzzword. Like the main message of the show, administering justice doesn’t just have to happen inside a court – in fact, that should be our last line of defence.

So I’m glad that we are all learning to stand up for what is right, to speak up for what is true and to defend the voiceless.

At the same time, we must not forget about mercy. Mercy as we correct others, mercy as we help others to broaden their perspectives, mercy as we offer people second chances.

On preparing for the role of Judge Sim, actress Kim Hye Soo said: “I started to really think about the social, structural framework that deals with juvenile crimes.

“I really wanted the series to come out well and do a good job in portraying the issue that we should be discussing in real life. I wanted it to resonate with the audience and offer a chance for people to change their perspective.”

She also reflected on cases where people felt that the rulings weren’t heavy enough to match the public anger: “Many would blame the judge, saying, ‘That’s why our society is like this.’

“But as I took part in this series and talked to such judges, I learned about the enormous responsibility and serious sense of duty they have in their jobs.”

In a broken world, it is almost impossible to make it up to the people who suffer unjustly.

What do you say to a mum whose child was murdered? Or someone who has been sexually assaulted? How can there be “true” justice when someone’s life has been irrevocably damaged? They are never going to get back what they’ve lost.

But just because there isn’t a perfect solution doesn’t mean we don’t try to make the best with what we can – to alleviate the pain of the victim and to rehabilitate the offender.

It takes a village to raise a child, and I hope we all find our way to make the world a better place.

To be honest, I don’t have all the answers. But I know, like our two protagonists, justice and mercy have to work hand in hand.

As Christians, when we’re able to do both, we reflect the character of God. Even as He is merciful, God is also – at the same time – just.

- Is there an area of injustice you are passionate about?

- How do we respond when we encounter injustice around us?

- How might God’s definition of justice inform how you view wrongs done to you and others?