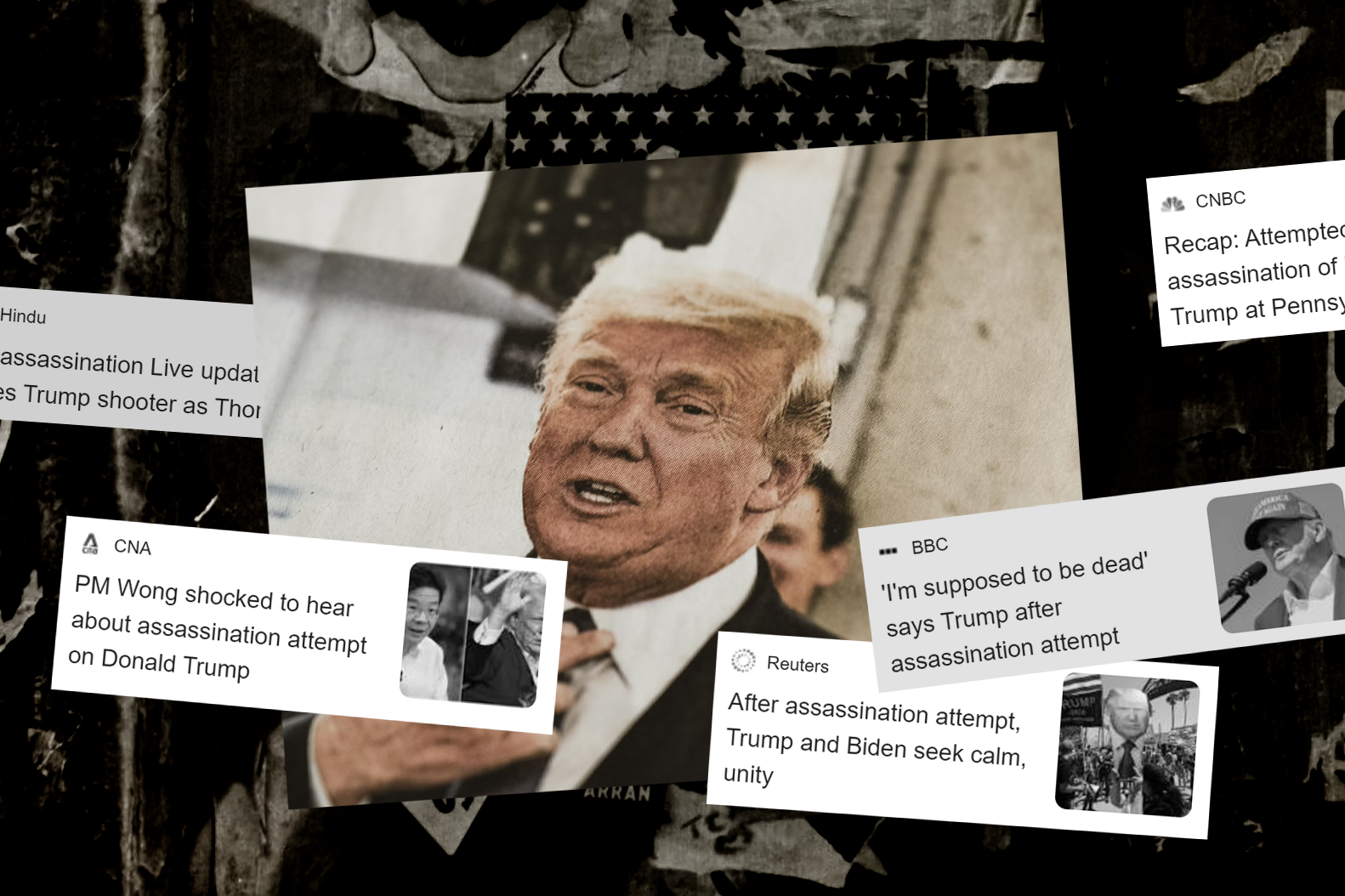

Growing up, I was always the “big kid”. King Kong, my mother would affectionately call me (which really, just meant “fat”).

When I was in kindergarten, I was a head taller than everyone else. My height was referred to as an oddity by my classmates. To them, I was just huge — like the beanstalk in Jack and the Beanstalk.

In a bid to diminish my beanstalk image and nurture me into a graceful ballerina, my mother enrolled me into dance class against my wishes.

It just made things worse: the instructor hated me, and at one time even called me an elephant in front of everyone else and their parents.

At that time, I was only seven. But, somehow, I had already internalised the fact that being of a bigger frame meant that I was the default “fat kid”. And by putting on that “fat kid” identity, I had inadvertently let my self-esteem plummet.

My body made me feel ugly, so therefore I was. My body felt like it wasn’t good enough, so therefore I wasn’t.

My body made me feel like I was always taking up excess space, so I spent my entire life trying to take up less.

Live in the shadows. Never initiate anything. Stay in my lane. Don’t speak if no one asks for my opinion.

My “fat kid” identity made me loathe myself. I felt like something was wrong with me. I got mad at myself for loving food so much. I hated myself for feeling hungry. And so I spiralled into a decade of disordered eating.

Disordered eating refers to food and diet behaviours that don’t meet diagnostic criteria for recognised eating disorders (EDs) but may still negatively affect someone’s physical, mental, or emotional health. Warning signs include chronic dieting, skipping meals, a fixation with body image and engaging in compensatory exercise.

There is healthy eating, extreme eating patterns that would count as an eating disorder, and then there’s this guy in between – disordered eating.

Control (and losing it)

At my lowest point, I would only have a banana for breakfast and a Nature Valley peanut butter crunchy granola bar (I can still remember the smell and the crunch of it as I write this) in the evening.

I would be rolling over from gastric pain, but it didn’t matter. I was proud of myself. Only 289 calories.

The more my gastric hurt, the better, because it meant that I was eating little.

And then there were brief periods of time when I’d completely lost it. In one school day, I would have:

- Shin Ramyun for breakfast

- A McDonald’s Sausage Egg McMuffin for brunch bought by my friendly deskmate

- This delightful teriyaki chicken rice bowl for lunch from the school canteen

- Gelato with waffles after school (anyone remembers 1-for-1 Gelaré waffles?)

- Another serving of cup noodles in the evening at the convenience store after my CCA (just sometimes!)

I went back and forth on this cycle of undereating and overeating, and I hated myself consistently.

Not only was I the “fat kid”, I was now also a loser and a failure who had no control.

Don’t you think it’s embarrassing for our future kids if we don’t look good? I love you, but more if you have a toned body.

During that time, there was no proper vocabulary or conversation about these things that I was going through.

If someone was undereating, we simply just attributed the behaviour to dieting. If someone was overeating, we would just say that he or she is greedy. And in the Singaporean culture that I grew up in, dieting was a virtue to have.

My parents complimented me whenever I had little or no appetite. My mother would literally remove the plate from me halfway through a meal. Every dreaded family gathering was often plagued by remarks about weight and appearance.

I was not spared even in a short 30-second elevator ride – my neighbours would make comments about how much I had grown, something that I took personally as a direct critique on my appearance.

Exercises and exes

All my life, I had a toxic relationship with exercise. After that very public “dancing elephant” incident, my mom put me through a military drill-like exercise routine.

On days that I didn’t have school, she would wake me up as early as 5.30am in the morning to go for a run. If I even dared to stop for a bit while running, she would shout at me like a drill instructor to keep going.

In school, I was always picked on by my P.E. teachers for my lack of talent in the sports department. One year, I failed my standing broad jump in a physical fitness test.

“Your legs are so long, but you don’t even know how to jump?” In my mind, I blamed my lack of sporting talent on my size. I couldn’t do anything well because I was “fat”.

I would try to make up reasons to get out of P.E. lessons, because I would much rather be in an extra period of maths class than that.

My ex-boyfriend had picked up on my disordered eating patterns and told me that I had to start keeping a food diary and count my calories.

While I had first thought of this as kind and well-intentioned, it further instigated the inner demons that I was already fighting.

He would point out items in my food log that he didn’t approve of. Bread, pastries, cakes. Sweet stuff. Carbs. All the things that I loved.

“You should ask your mom to stop baking. She’s making it worse for you,” he would say. I was mad, but I didn’t say anything. I was the fat kid, and fat kids don’t get to defend themselves.

As our relationship progressed, my diet would swing from one extreme to another. Nature Valley granola bars became my best friend, as were oat porridge and bananas.

If that wasn’t bad enough, he then started to gaslight me into exercising to lose even more weight.

“Don’t you think it’s embarrassing for our future kids if we don’t look good?” When my ex asked me that in reference to my lack of exercise, I felt guilty that I was still not good enough.

I began to work out in order to appease him. I would send him “proof shots” of me on a run or at the gym.

But what was stressing me out was that I was neither shedding any weight nor looking significantly smaller.

And so I ate less, exercised more. Ate even less. Exercised even more. My self-esteem plummeted to its lowest.

“I love you, but more if you have a toned body.” Hearing that, I finally saw that a relationship as toxic as this had no future at all.

One of the last things he said to me was, “I really hate that low self-esteem of yours.”

Perhaps there was some truth in that statement. In the aftermath of that very traumatic breakup, I lost 5kg in a week. An alarming number to many, but a pleasant surprise for me.

I continued to lose more weight because I had spiralled into mild depression, and I was not eating or sleeping at all. I dropped four sizes in just under two months, and people even came up to me to ask if I was sick.

In my mind that had been twisted by years of unhealthy eating patterns and poor mental health, I felt happy for once.

Maybe I was finally starting to become like everyone else. This is the part where I finally turn pretty.

My body made me feel like I was always taking up excess space, so I spent my entire life trying to take up less.

Recently, I had the chance to go through old photos from that era again. I felt a pang of sadness.

In a whole bunch of those photos, I was at my skinniest ever. I should be happy. I thought I was. But all I saw were eyes that were devoid of joy and confidence.

What I saw was a girl who had been thoroughly trampled on; her self-esteem completely shattered. She was (maybe) pretty, but she was also empty.

I finally looked good, but at what cost?

Water, working out and… avocados?

In the last few years, with growing conversation and awareness given to body image and mental health struggles, I had thankfully taken significant steps out of my darkest phase.

Sure enough, I still had insecurities about my body, but I knew that I was in a much better space. But a day came when my colleague dropped me a text out of the blue:

“For some reason, God says drink lots of water and get some exercise in. And for some weird reason, avocados. But He stressed it’s for internal goodness – nothing to do with external. Don’t ask me why!”

Unknown to that colleague, I had been seeking treatment for an inherited metabolic disease. And when he sent me that message, I had a blood test coming up in three weeks’ time.

My colleague continued to emphasise the fact that the exercise was not for any outer appearance. That was when I felt something lift off my chest.

All my life, I had exercised to look good. Or I was forced to. Or to make others happy. Or to make sure that I could defend my eating habits.

Even when I was exercising under my doctor’s request, I knew that I was only doing it because I only wanted to be faultless.

The long and short of it: I stopped exercising completely after the latest round of blood test results because exercise had done nothing to improve my condition, so I just decided to give up.

I saw exercise as punishment for being the “fat kid”. I never truly wanted to do it for myself.

So in the weeks that followed after that text message, I struggled. I was afraid that once I took the first step in restarting my exercise routine, I would lose control and spiral. I was scared of falling back into the same toxic patterns again.

As my eyes went over the same message over and over again, I was fixated on the words “internal goodness”.

God knew. There has been little internal goodness with regards to my body image for the last two decades.

I was filled with self-hatred and self-condemnation. I had an unhealthy relationship with food and exercise. I had an unparalleled fear towards exercise that was out of this world.

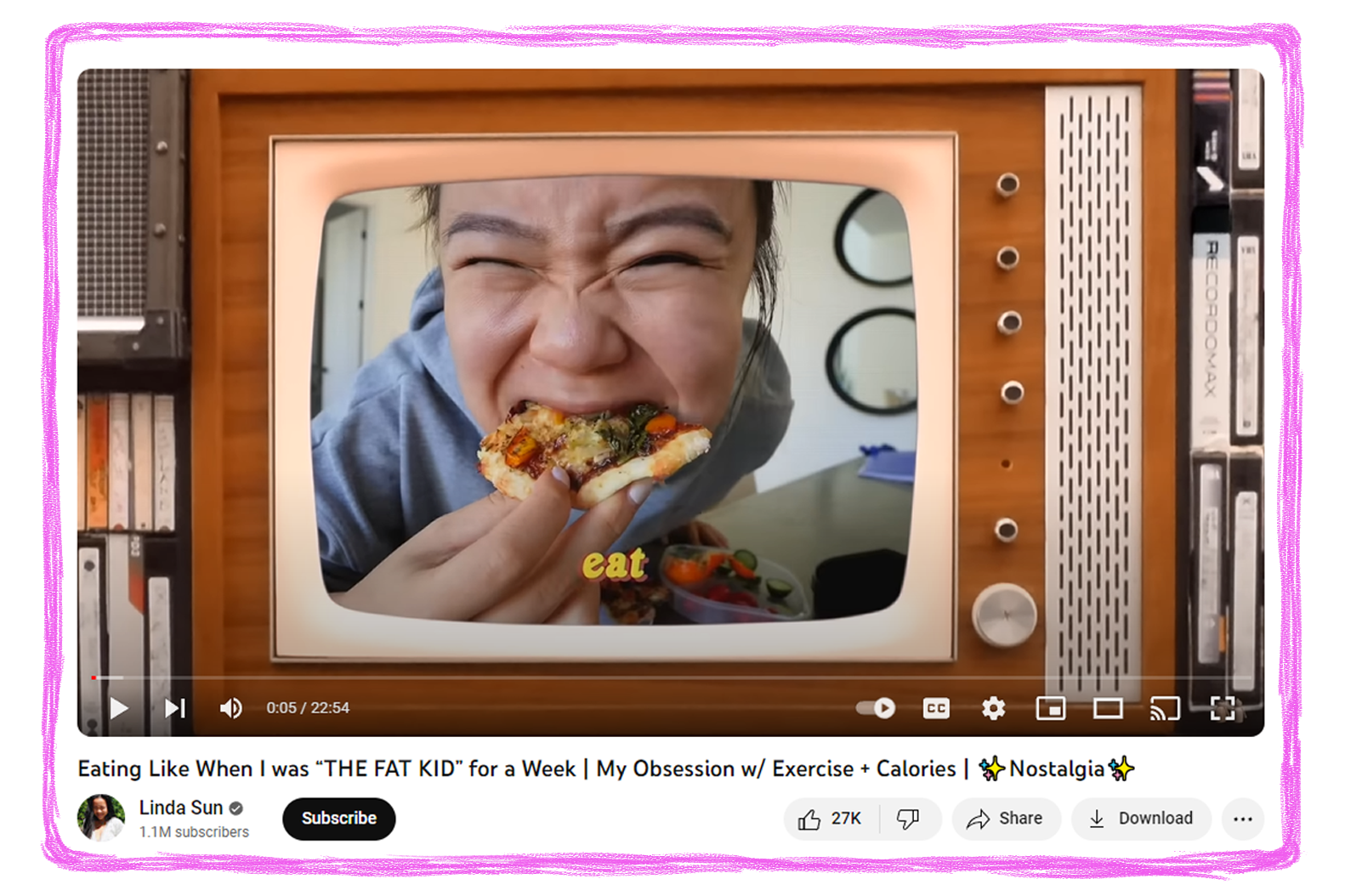

It just so happened that the same night, I randomly clicked on a recommended video from Canadian-based content creator Linda Sun.

Linda, like me, had always struggled with growing up as the “fat kid”, and also spiralled into unhealthy relationships with extreme dieting and workouts. Her video felt like a warm hug to my seven-year-old self.

I decided it was time I did something for myself. And so one evening, I changed into my running gear and went for a run for the first time in a long time.

For once, I was free. Free from all the expectations that had been pinned upon me. Free from all the naysaying that had been going on for decades. Free from the mental cage that I had trapped myself in.

I was free.

The road to recovery may be rocky, but we’ll get there

It’s been over a month now since I’ve started doing that. I’ve discovered new things about myself that I never knew.

I even had an honest reflective conversation with my mother about how my childhood experiences had traumatised me. Thankfully, she was also humble and gracious enough to acknowledge her involvement in causing some of my distress.

But the road to recovery and self-love is not without its challenges.

An unhealthy relationship with food and exercise doesn’t happen overnight. The things that people say to us, the lies that we believe, the culture around us that has shaped and influenced minds… Little by little, these things add up. And before you know it, you’re just in too deep to stop.

On some days, I still catch myself mentally tabulating the amount of calories I consumed. Or dragging myself out of bed in the middle of the night to do my nightly weigh-ins. Or berating myself after I had accidentally gone into stress-eating mode.

I’m still a work in progress. But boy, am I relieved that the process of undoing all those years of disordered eating has finally begun!