The internet is a harsh place to live in these days.

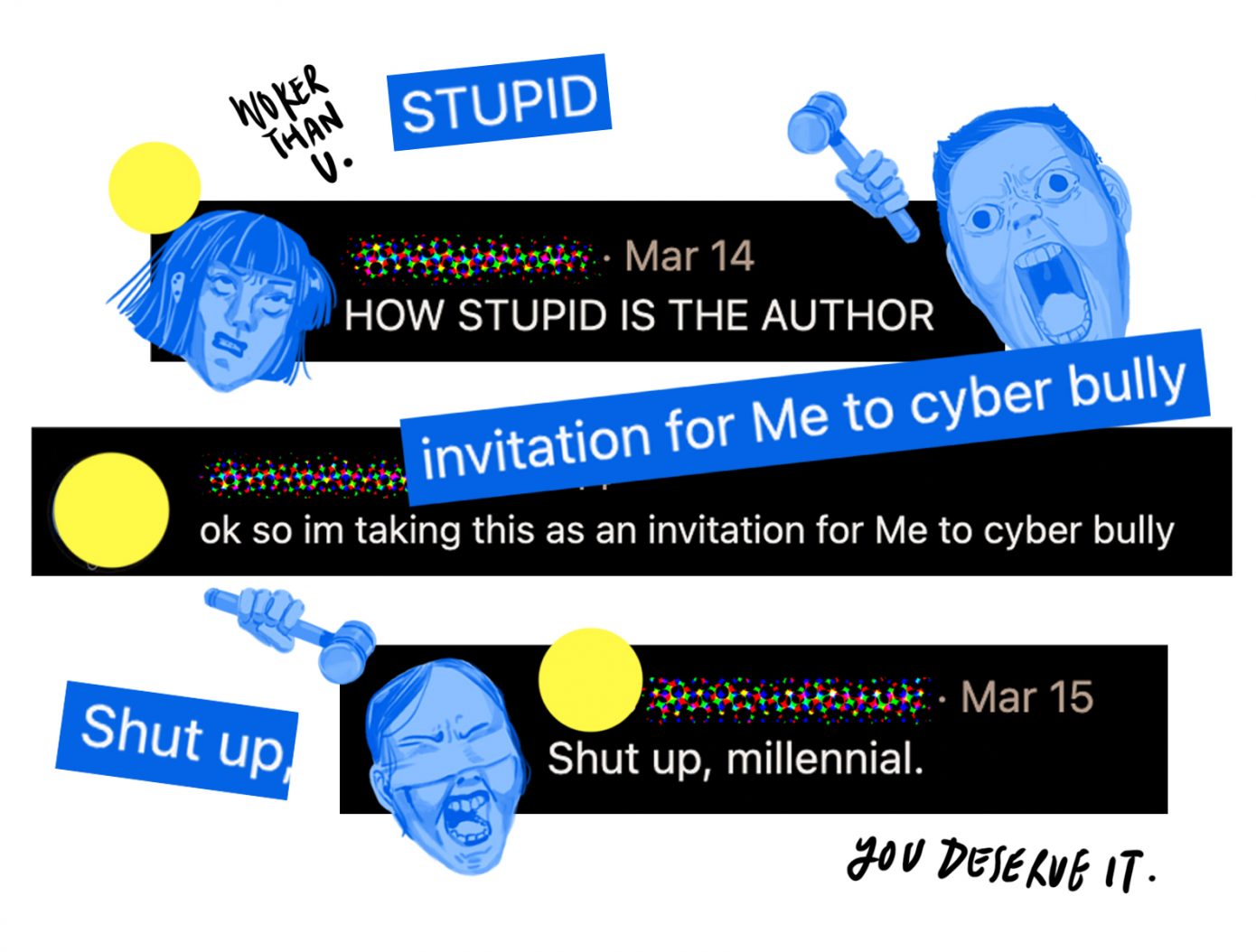

This year, we saw a university student flamed for voicing out against the woke movement, the anger against the People’s Association’s misappropriation of photos and – dare I say it – the vitriolic comments during the Thir.st modesty saga.

And the latest: the Ministry of Education being criticised for how they handed the River Valley High School (RVHS) situation. Journalists in Singapore were also called out for the lack of sensitivity by camping outside school grounds.

I get it. There are issues we need to address. I’m glad that these views are represented so that people who are hurt are being heard.

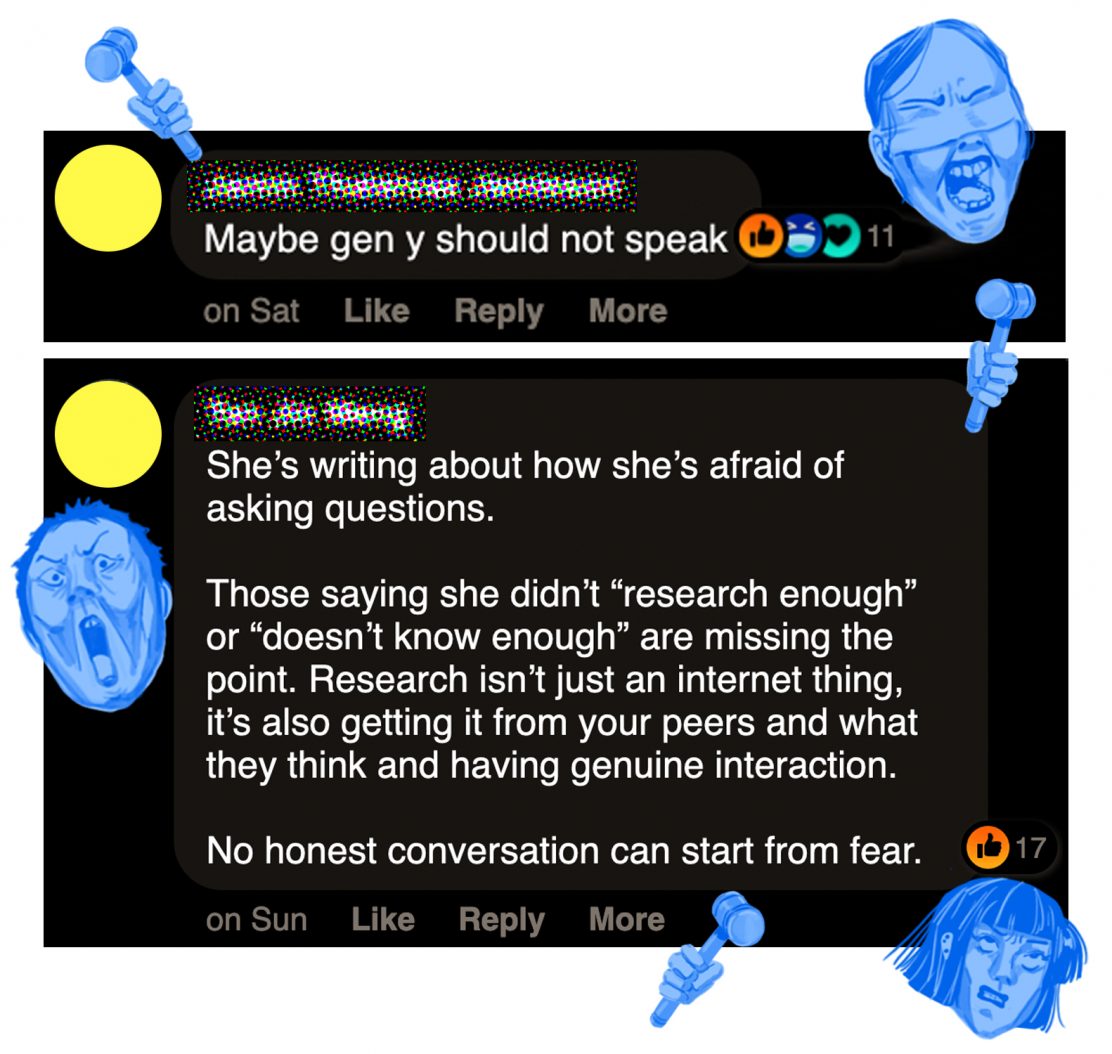

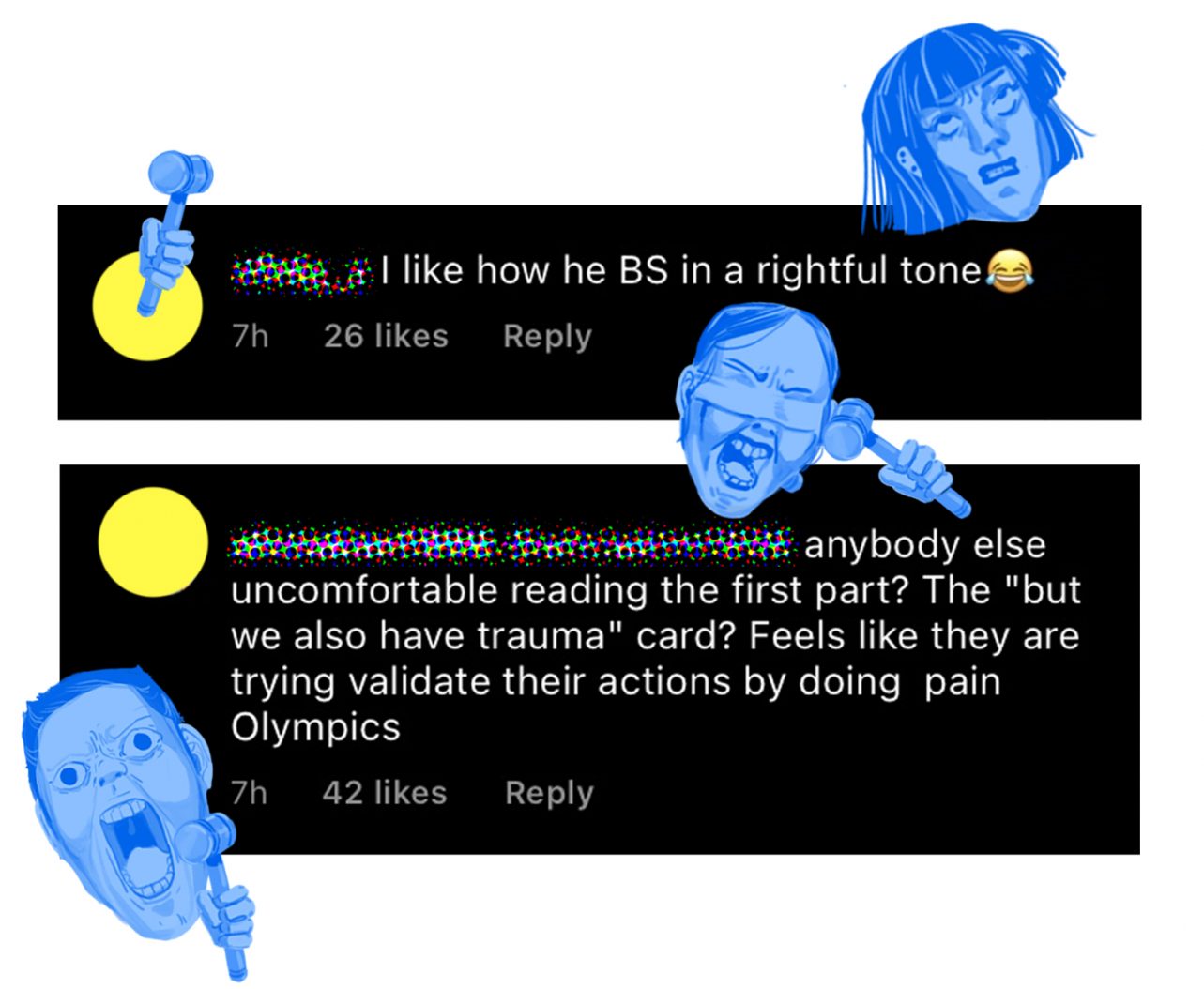

But in the fight to represent the marginalised, I have also observed that there is a growing tendency to be aggressive towards those who are of differing opinions.

These are just a few examples of how brutal people on social media can be.

It appears that intolerance has become one of the extreme outcomes of critical theory, which seeks to reveal and challenge the power structures in society through assessment and critique.

Individuals subscribing to critical theory might ask questions like:

- Who are the marginalised groups?

- What are the institutionalised structures that perpetuate these issues?

- What can we do to balance out the power play?

Critical theory does help us to keep each other in check and regulate the different forces at hand.

For example, issues like rental racism and discrimination against migrant workers would probably be swept under the rug if not for people who raise questions about the system.

But there is also a tendency for us to escalate from wanting to speak up for the voiceless to silencing the voices of others. In recent years, we’ve seen critical theory playing out in various forms.

On their own, these phenomena don’t seem that much. But when put together, we see a clearer – and dangerous – picture of where society is heading.

On their own, these phenomena don’t seem that much. But when put together, we see a clearer – and dangerous – picture of where society is heading.

Imagine a world where ignorance on social issues gets harshly critiqued. Those who are not educated enough to speak up about these issues have their opinions silenced too.

Imagine there are unspoken rules dictating how one should act and think towards social issues. And how there would be social repercussions if the correct sentiments are not expressed should one decide to speak up.

This creates a culture where, on one hand, you have people who regurgitate slogans and catchphrases without fully understanding the issue because they deem it as the socially right thing to do.

On the other hand, others who might have alternative but valid opinions stay silent for fear of being judged and shamed.

Sadly, the depiction isn’t too far from reality.

Not supporting any of the minority groups? Have a different opinion? Questioning why a cause should even be a cause in the first place? People could say:

“You’re an unenlightened, privileged individual who is so blinded by the cultural hegemony that you don’t even understand the systematic oppression others are under.”

Alright, I might be exaggerating. But you get what I mean.

Once again, I think it’s great that people are trying to create conversations because they want to raise awareness for certain social issues.

But the call-out culture that society has adopted to approach these issues is problematic.

Off the top of my head, I can think of two reasons why it is not only unhelpful, but also detrimental to the causes we are supporting.

1. ISSUES ARE OFTEN MULTI-FACETED

When I first saw the viral post on how media personnel were camping outside RVHS where a murder had happened two days before, I was incensed.

Like many, I felt sorry for the students who had to deal with the media while still reeling from trauma and shock.

But while my initial knee-jerk reaction was to blame the media for harassing the students, hearing a reporter’s perspective made me realised that he/she had a valid point too:

“We are sorry for the stress we’ve caused the students and staff of the school, but please try to understand that we are doing our jobs. Please stop hating on the media. It’s not that we are heartless or insensitive people. We are grieving with you too.”

I’m not saying I agree with the act of camping outside RVHS, but I understand that journalists are caught between a rock and a hard place. This is exactly why it is a dilemma – because there is no easy answer.

On another issue – the hot-button topic of race – Minister of Finance Lawrence Wong recently described how racism in Singapore can’t just be explained away with “Chinese privilege”.

At a forum on race and racism last month, he pointed out that while the Chinese are the majority race here, there are also Chinese-educated citizens who feel that they are at a disadvantage in our English-speaking society.

“‘What do you mean by Chinese privilege?’ they will ask, for they do not feel privileged at all,” he said, citing the closure of Nanyang University and the eradication of dialects as examples.

“Let me be clear: I am not saying that we should refrain from voicing our unhappiness, or that minority Singaporeans should pipe down about the prejudices they experience,” he continued.

“On the contrary, we should be upfront and honest about the racialised experiences various groups feel, and deal squarely with them.”

A discourse is only healthy if we allow for different opinions to be aired.

I agree with Minister Wong. Most social issues are dynamic and complex in nature.

Just because someone is in a majority group doesn’t mean that they are automatically in a privileged position. At the same time, it doesn’t give the majority the right to downplay the struggles faced by minorities either.

This is why studies and research are conducted to properly understand the different factors that come into play.

But passing strong sweeping statements not only shuts people off from having conversations — it may also create even more misunderstanding towards the problem itself.

Instead, let’s hold back our judgment and hear the different points of view so that we have a more holistic understanding of the issue at hand.

2. IT CREATES AN OPPRESSIVE ENVIRONMENT

I recently watched this interview with a North Korean defector, Yeonmi Park, who described what living under oppression was like and the treacherous journey to freedom.

But when she finally escaped from North Korea and went to study in the US, she found that political correctness was so pervasive even in the land of freedom.

Recounting the one time she got into an argument with her professor, Park described: “She was saying that letting men hold doors for me means that I was giving in to them. That they were overpowering me.

“I was like, ‘No, isn’t that kindness?’ I would hold the door for people too. It’s not like I’m trying to signal that I’m more powerful than them.

“She was like, ‘Yeonmi, you’re so brainwashed by North Korea.'”

This was one of the many examples she gave on how she had to defer to what her classmates and professors thought were the politically correct answers.

“It gave me a lot of chaos,” shared Park. “Did I become free? Where am I? Is there truly any free place in this world?”

Yes, we need to speak up for the voiceless. But wouldn’t it be ironic if we, in the process of speaking up for the voiceless, suppress the voices of others?

While it is great that we speak up for a better society, standing up for social issues has somehow become a game of who shouts the loudest (and sometimes, vilest).

I may be a completely neutral party wanting to learn more about the issue, but looking at the comment sections sometimes does scare me into silence.

A discourse is only healthy if we allow for different opinions to be aired. Only through open conversations can we uncover underlying assumptions, learn from various perspectives and achieve real understanding and transformation.

In fact, this may even be more helpful for the causes you support because it surfaces the misunderstandings that people have, giving you an opportunity to address and clarify them.

Every message we send out can be a stone that we cast or a hand we reach out to.

Being critical helps us to identify the many underlying issues that the world has to rectify. But even as we are critical, we need to leave room for error, for conversations, for forgiveness and for growth.

Think back to the times where you’ve made insensitive remarks, held prejudices and committed offences towards others. We were, at some point, the ignorant fool that we now so harshly judge. We probably still are, some way or another.

It doesn’t mean we have lost the right to criticise – it’s still important to speak up for what we believe is right – but it means that we do so constructively and with humility.

The internet is a harsh place to live in these days. Every message we send out can be a stone that we cast or a hand we reach out to.

And I pray that in standing up for the voiceless, we don’t inadvertently silence the voice of others.

- How do you react when you see/hear things that upset you?

- What are your thoughts about sharing your views on social media?

- What does it mean to be a witness for Christ?