For every 100,000 people in Singapore, around 8 are lost to suicide every year. Although there was a slight dip in the total number of suicides reported in 2017, the number of seniors taking their own lives hit a record high since tracking started in 1991.

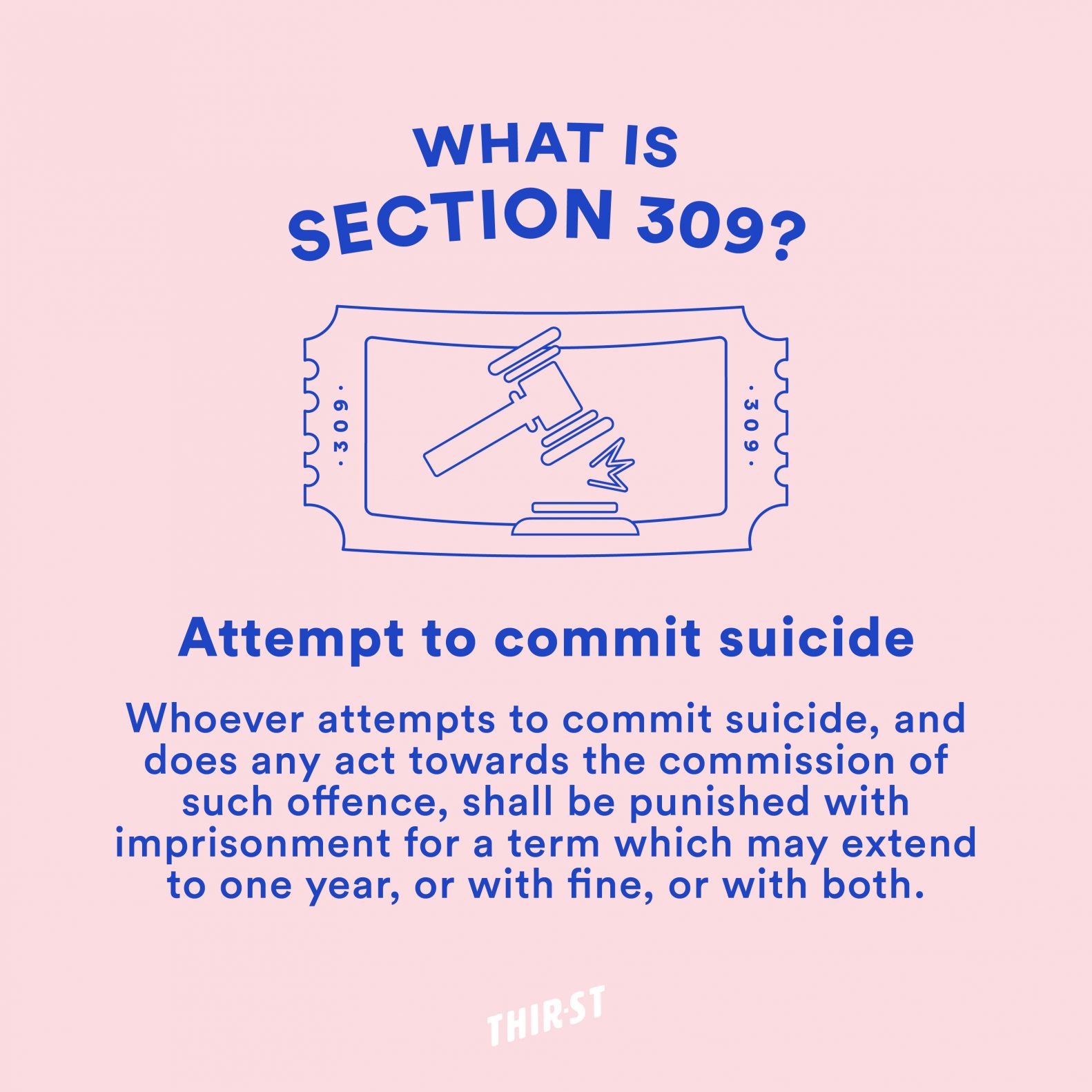

It’s against this backdrop that the Government has accepted a recommendation by the Penal Code Review Committee (PCRC) to decriminalise attempted suicides, as it takes the view that treatment rather than prosecution is the appropriate response in such cases.

The repeal of Section 309 was included in the Criminal Law Reform Bill, which was given its first reading in Parliament last week. A second reading is expected to take place in May.

However, this is a move that has drawn both praise and concern.

In accepting the PCRC’s recommendation, the Government said it has not shifted its position on the sanctity of life.

“This is reflected through the continued criminalisation of the abetment of attempted suicide, as well as amendments to other legislation to provide the police with the powers to intervene to prevent loss of life or injury in cases of attempted suicide,” the Ministry of Home Affairs said in a press release.

In reality, however, it’s unclear what practical difficulties the authorities would encounter in enforcing treatment for a non-offence, or how easy it would be to determine abetment when those who choose to end their lives can claim all responsibility and face no criminal liabilities. In addition, how will this legislative change blur the line when it comes to a person’s right to die?

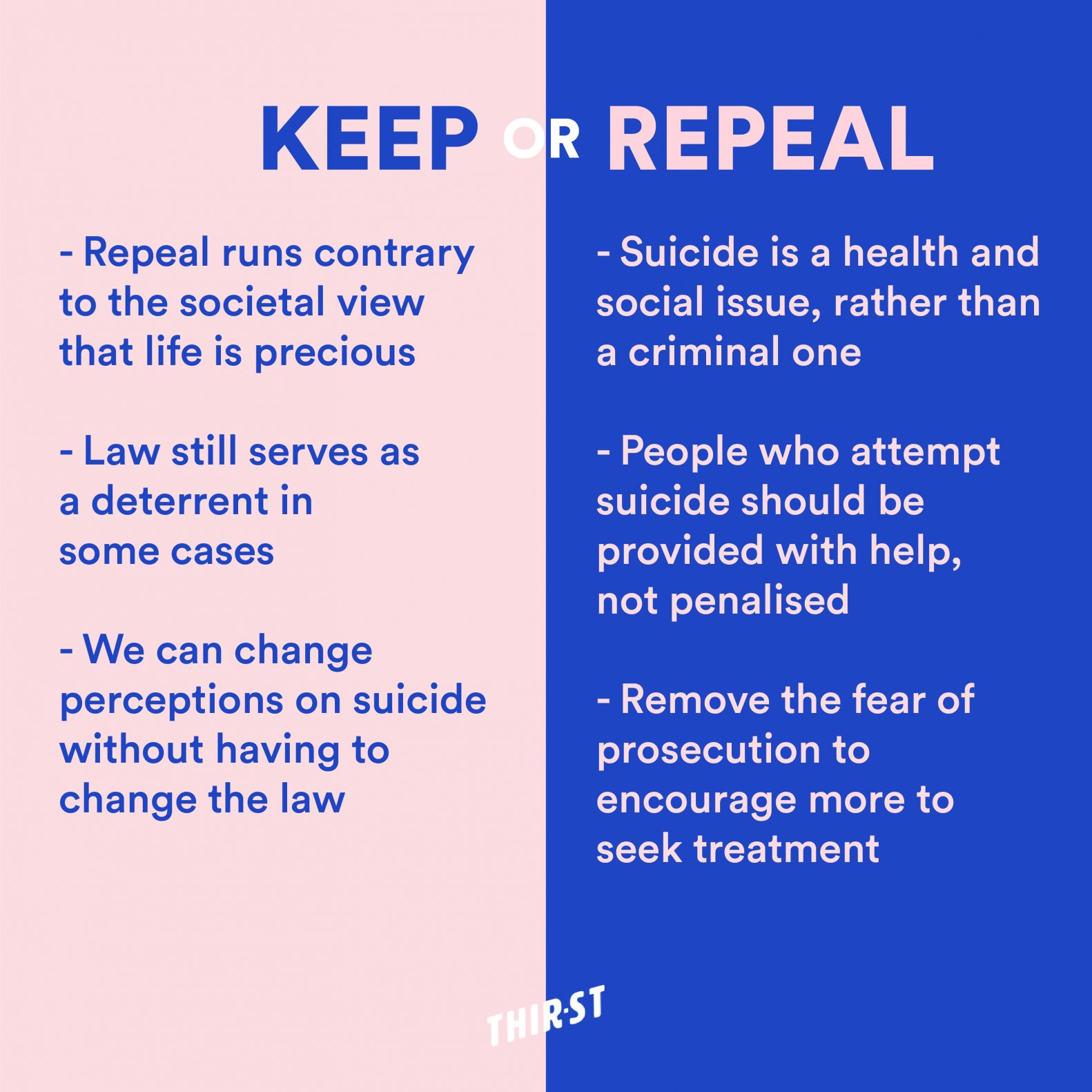

These are the main lines of argument:

We spoke to professionals in the legal and social service sectors to explore the broader implications on society.

- Isaiah Chng, Board Chairman, Empower Ageing

- Justin Mui, Executive Director, Lutheran Community Care Services

- Senior civil servant with extensive experience in the legal sector, who requested to remain unnamed for this article

A key argument for the repeal is that the focus should be on effective treatment rather than prosecution. But does Section 309 fulfil a symbolic role we should be more conscious of holding?

LEGAL PROFESSIONAL: Criminal laws were, and still are, enacted accordingly to reflect disapprobation by society against certain kinds of conduct. Penal laws are not always only about punishment for crime.

Once a particular conduct is made criminal in nature, several other objectives would also be met: Preventing other people from committing the same act (deterrence), allowing a framework of rehabilitation and restoration to take effect, and enabling social support for those affected by the crime to be tapped into.

In the case of Section 309, treatment can be, and already is in most cases, provided for those who attempt suicide. Instead, we are removing from it the other important effects of retaining it in the Penal Code.

It’s also worth pointing out that prosecution of suicide attempts is extremely rare in Singapore.

ISAIAH: I don’t see a need to repeal this moral signpost. With the law, there is strong and credible code to seek reference from, while public education can rally people to believe that life is precious so that they fight instead of giving in to hopelessness.

Working with seniors for the last 12 years, I’ve observed a prevailing thought among seniors who are not diagnosed with a mental condition but who want to end their lives because they want to relief themselves and/or their family of the burden of caring for them. This makes seniors vulnerable, and with an ageing population, we’re risking an increase in suicide attempts.

The current repeal is proposed based on calls to reduce the stigmatisation and psychological ill effects on survivors of attempted suicide and their families. I agree that it may help them. However, it does little to help other potential attempters or improve the perception of the public at large.

JUSTIN: Suicide is likely not one’s first few choices of responding to difficulties and setbacks. It reflects a deep sense of hopelessness, from multiple attempts of coping or making things better, perhaps over extended periods of time.

The symbolism behind prosecution is that of accountability. In the context of suicide, that can be less helpful than that of love and support.

By decriminalising attempted suicide, what signal are we sending to society on the sanctity of life?

LEGAL PROFESSIONAL: The concern is that if an important symbolic law such as Section 309 is repealed, it may give way to arguments that in some cases e.g. mental illness, life is not worth protecting. That starts the argument, but when will that argument end?

It can be extended further and further in the future – to those who are terminally ill, to those moderately ill, to those who feel ill but are not, to those who make other people ill, and then eventually to people who are simply unwanted such as babies who are aborted at full term.

JUSTIN: Decriminalising suicide, and the absence of any additional measures and safeguards, can send a message that it is more acceptable for one to take their own life. However, I think there are intentions to put in place measures to allow law enforcement and medical professionals to enforce treatment when suicide attempts are made known.

ISAIAH: We’re making it clear to society that the sanctity of life is not important as people can still attempt suicides. Also, based on the recommendations there would not be mandatory reporting of suicides. How then do we know the impact of such an amendment?

Though we are implementing better support, the better support is not proven yet. So taking down this law does roll us back, especially since research has shown that when you repeal the law, suicide rates go up.

Having such a law can prevent people from taking the next step and give more time for help to be rendered. A near-suicide attempter I spoke with told me that he was aware of the existence of Section 309 while contemplating suicide, and it did deter him from attempting. Deterrence does buy time for society to reach such individuals. It’s worth keeping the law, even for one life to be saved.

Would this repeal lead us into a slippery slope environment where we would start exploring the possibility of legalising other forms of suicide, e.g. assisted suicide/euthanasia?

LEGAL PROFESSIONAL: Yes. Suicide is murder as defined under Section 300 of the Penal Code. Once that line is crossed, the question of the rightness of death by the hands of another person will be opened.

Currently there are plans to criminalise assisted death/euthanasia as a safeguard, but these safeguards will not hold water when the debate is revisited in 5-10 years. There will simply be no basis to distinguish between killing myself and authorising a doctor to kill me. What is the essential difference?

ISAIAH: Yes it will. That’s what we see in other countries. The Government says that they won’t let the law go down to decriminalising euthanasia, but who knows what the next Government/minister would do?

JUSTIN: Possibly, if taken from the view that this brings us one step closer to legalising other forms of suicide, though the Government and PCRC are explicit that abetment of suicide will still remain an offence. As it stands, it would take a lot from proponents of euthanasia to put forth compelling arguments in their favour.

How can we continue to protect those who might be struggling with suicide regardless of the changes in legislation?

LEGAL PROFESSIONAL: Treatment is necessary, but you cannot mandate treatment unless there is a court order. And you can’t get a court order unless there is a prosecution. It’s a chicken and egg thing. Without proper legislation, a person “invited” to go for free treatment (which is currently the case) can simply not turn up.

If the laws are changed such that suicide is decriminalised, it will be very difficult to enact collateral legislation compelling treatment/counselling. If so, it would be tantamount to saying that not attending counselling is a crime, which is absurd.

The other possibility is to say, attend counselling or I will charge you. But if the laws are not there for suicide, what do you charge the person with, reasonably? It’s hard to imagine how this can work in practice, although it sounds noble in theory.

JUSTIN: This creates an opportune time for creating strong narratives that emphasise the importance of building supportive relationships as well as equipping individuals with skills to engage in deeper conversations that allow for one to embrace vulnerability. No one should be facing one’s vulnerability alone.

Perhaps it’s time for a different conversation, “don’t take your life because it’s wrong and you can be prosecuted” can now be “don’t take your life because I value you, and will be hurt if you do so.”

ISAIAH: We need better equipping to identify potential attempters so that we can channel targeted help to them. Public education is also very important in the fight against the prevailing mindset of burden and hopelessness as increasing awareness can lead to positive outcomes.

We’ve done it before as a nation. Yellow Ribbon has successfully changed the perception of ex-offenders. No laws were changed to facilitate the positive change except allowing ex-offenders to have their criminal records removed. This can and should be applied to suicide attempters as an empathetic response if they adhere to help rendered to them.

With this Penal Code review, I see the opportunity for a better safety net for the vulnerable as well as the survivors. Let’s make this an exercise that will produce societal change instead of a change in the law, which has little effect on reducing and helping the vulnerable against suicide.