“I’ve always been looking for ways to tell their story, especially to get people to understand refugees a bit better,” Alexis had written in her latest text to me. “It’s a Chin refugee school, most of the kids are from Myanmar and they are of the Christian faith.”

“Is this something you might be interested to look into?”

On September 17, 2018, a regular Tuesday in the office and one week after I’d returned from a media conference in Yangon, Myanmar, my phone started ringing around lunchtime. It was an unknown “+60” number, from Malaysia, and a Whatsapp call, which meant it was free, so I picked it up curiously.

The girl on the other end sounded young, and as soon as I’d answered the call, asked if I knew a “Jane Tan (not her real name)”. I did, but this wasn’t getting any less strange.

Jane Tan was someone from Kuala Lumpur who’d reached out to Thir.st last year, and I’d met up with her for the first time when I was in KL for a seminar in May. I only knew her full name because it was in her email address.

Didn’t people get calls like this when their next of kin have been in an accident? Was Jane okay? But I’m not even her next of kin – or next, next, next of kin – why would they call me?

“Can you tell Jane that she’s left her wallet in a Burger King at the Sungai Buloh bus terminal?” the girl continued. “We found your name card inside, and thought you might know how to contact her.”

So the problem was solved, but the mystery was still in question. Call it a job hazard, but I couldn’t help but wonder: Was that all to this serendipitous encounter? Why had something as bizarre as this happened out of the blue?

“Thank you for helping Jane,” I texted after sending her Jane’s phone number. “I’m Joanne by the way – great to meet you.”

“Nice to meet you too,” she replied. “I’m Alexis. Your name card says that you’re a Creative Producer?”

Within the next 24 hours, I’d not just befriended Alexis over Whatsapp, but also found myself agreeing to come to KL to tell the story of the Chin Student Organisation (CSO), a school for Burmese refugee children that she had been regularly volunteering at.

She put me in touch with the head teacher in charge of this particular centre, one out of four CSOs in the KL region, a 20-year-old Burmese named John Lian, also a refugee from the Chin state in Myanmar.

“You are always warmly welcome,” he wrote to me in an email.

That escalated quickly.

“This is either an elaborate scam to lure me to Malaysia to kidnap me, or God is nuts,” I remember telling Christina, our Visual Editor, as I watched the almost ludicrous situation unfold. “God is nuts,” Chris replied confidently.

She was right.

![]()

The Chin Student Organisation was started in 2005 by Burmese university students who noticed a growing number of Chin children on the streets of KL. The Chin people are one of eight main races in Myanmar, each with its own distinct language and culture.

As refugees are not recognised as citizens, official social policies and schemes such as education are not extended to the thousands who have temporarily set up home in the country. Their stay normally lasts for years as they wait out their situation.

So as much as Malaysia has a friendly relationship with refugees, who are further protected by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), this is no promise of a comfortable life, with most Burmese having to earn their keep through odd-jobs and manual labour – where they are highly vulnerable to exploitation – if they can even find paid work at all.

With over 42,000 Chin refugees in Malaysia, working parents and no proper school to attend has left many, many young children and youth on their own. John Lian, my contact at CSO Puchong, came to KL at just 15 years old, together with his older brother. Their parents had arranged for an agent to bring them over to Malaysia for a better life while choosing to remain in their village, a largely farming community.

“The main reason is that the government does not support us,” John explained in the email interview we had before my trip there. “Almost every day there was a war happening in the Chin state. There were Burmese soldiers everywhere and they used to come into our village, our houses, our farms, our churches and take everything they wanted.

“They wanted us to change our religion because we are Christians. They beat us, forced our people to work for them or join the military. We could not live freely, we could not go to church or celebrate our cultural days. Living there did not feel like home anymore.”

But the transition out of the turmoil in his homeland offered little respite. After enduring a harrowing journey from the western Chin state down to Malaysia that involved lengthy stretches of walking and squeezing at the back of a truck with 20 other people, John found himself in a whole new world, miles away from his parents and with little to his name but a refugee card from the UNHCR.

“When I first came here, I was very lonely because my brother had to work,” John told me when I finally visited the school in November. “We couldn’t go outside as and when we liked, so I always stayed at home. I missed my parents and I didn’t have any friends.”

But it wasn’t long before John started attending classes at CSO Puchong, which was close to where he was living at that time and attended by the other Chin refugee kids in his neighbourhood. The school was run by Chin teachers, most of whom had gone through the same system, which uses the Singaporean Primary School syllabus. This was where he quickly picked up English and found a new home among the other refugee children.

Unlike one’s immediate assumption of a school compound, the Puchong centre is really just two floors of a shophouse along a dusty suburban stretch reminiscent of Joo Chiat Road. Somewhere between a church’s unit and a massage parlour is a flight of steps leading up to a telling rack of school shoes, the only sign that this is place where children are – besides the faint chatter of little voices from behind closed doors.

Today, John has become the head teacher and coordinator of the Puchong branch, just three years after leaving the school to work in a restaurant because there was nothing left to learn – there were no more teachers beyond Form 1, a rough equivalent to our Secondary 1. He was only 19 when he was called back to CSO Puchong to help teach because there were only two full-time teachers left in the centre.

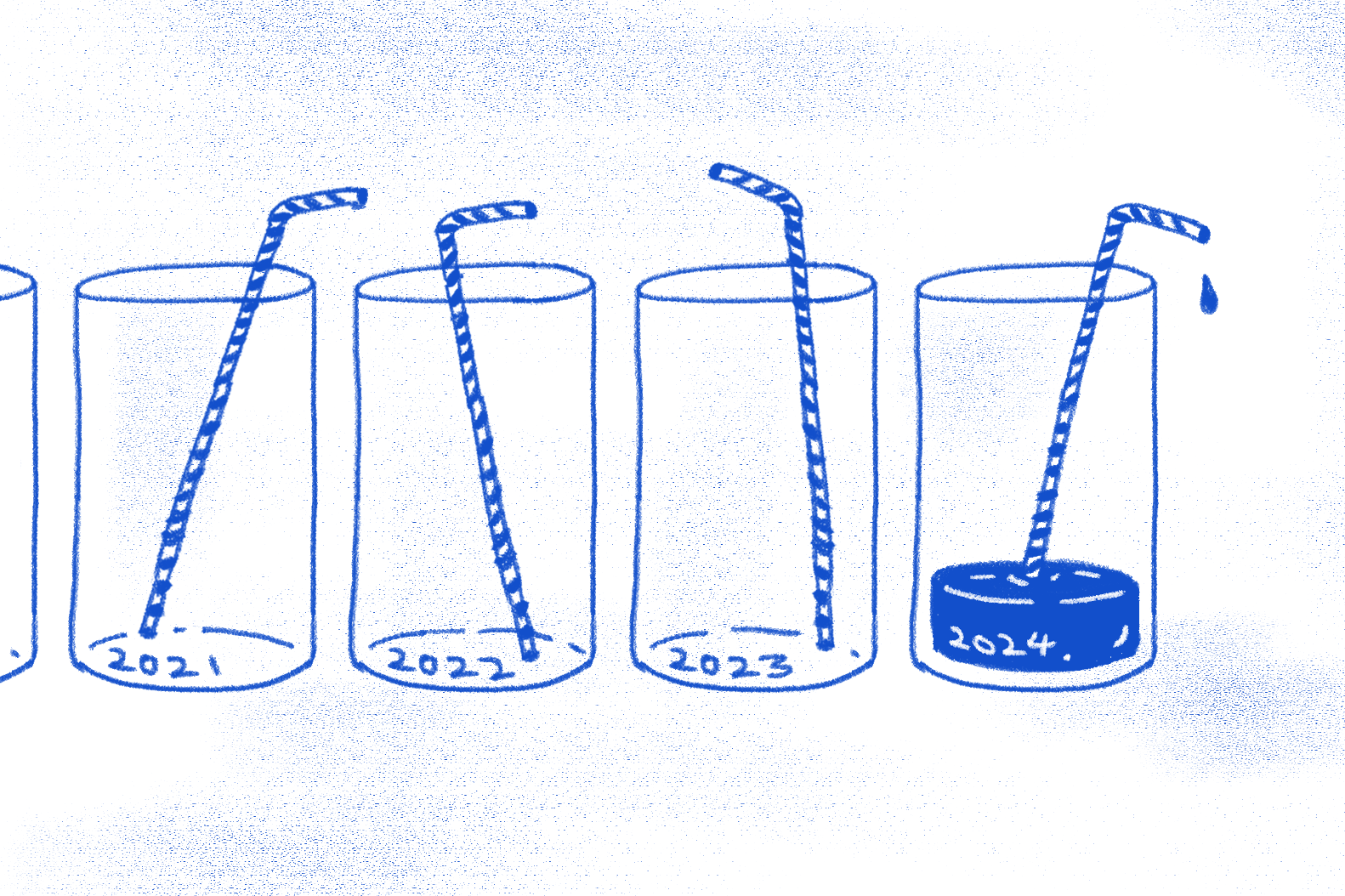

This is how the centres are run: Full-time teachers, usually Chin refugees themselves, hold the fort until the UNHCR finds a country willing to take them in, such as Australia, Canada, Norway, New Zealand, USA, or UK. When this happens, someone else has to take over, such as in John’s case. The previous head teacher, Joseph, barely in his twenties himself, had been relocated to Australia, leaving CSO Puchong under John’s care.

There are currently only four full-time teachers at CSO Puchong, and two are essentially still teenagers. The school relies on the goodwill of volunteer teachers, such as Alexis, the girl who’d called me, and if there’s no teacher available for a certain day’s lesson, there’s no lesson. Also, no one is paid for this work, not even the full-time teachers themselves.

The centres are given some money to run by the main CSO office for food and other necessary expenses, but everything else there is donated, John said. The teachers live “on campus”, two rooms dedicated to living quarters, and they cook their meals in the kitchen. They receive donations from a few local churches, but it’s just enough to survive.

“It’s very hard to find someone who will work at the school full-time and not get paid,” John admitted. “And having no sponsorship is the most challenging thing – we have a few sponsors, but no main sponsorship. There were many times I had to beg people for money, beg them to volunteer at the school …

“It is hard when I am judged by older people because of my age and lack of experience, but for me, I want to help the kids in any way I can and stand up for them even though I’m not trained and very young.”

He continued, “I love supporting them with what knowledge I have. Even if I have to study before I teach them or teach more classes because we don’t have enough volunteer teachers. Their future and life depends on me.”

Sitting in a simply furnished office in front of a whiteboard that has the week’s timetable neatly written out, it is hard to believe that John Lian, with his slight build and boyish disposition of someone barely out of his teens, is essentially the principal of this school. But there is a weight in his words, a trace of a man much older than the boy before me.

Only when I ask him what his dreams are when he finally gets to relocate to Australia, his resettlement nation of choice, is he 20 again – old enough to say “Civil Engineering” and “a successful businessman” yet heartwarmingly youthful when he punctuates his answers with “but I don’t know yet”.

It’s a familiar expression of young people his age, but for John, who was raised in a Christian family back in Myanmar, not knowing what the future holds has been a matter of life and death for a long time.

“When I first arrived in Malaysia I was afraid,” he said. “Living as a refugee is really hard. Every day I am afraid of the police, of thugs and accidents. If something bad happens, there is no one who will take full responsibility for us.

“But I know God is with me and that He will protect. I put Him first in everything that I do and pray when I face trouble.

“I know we cannot expect good things every day; we have to face difficult things. So I pray for the strength to continue, for God’s help to live every day and have a strong heart.”

Most of his prayers are not for himself, but for his students and other refugees like him. Too many of his own friends have dropped out of school in order to earn a keep, and picked up bad habits such as smoking and drinking.

This is why John continues to teach at CSO, even though it isn’t a paid job, so that the children in his charge will be brought up well and kept off the streets.

“What I love most are our morning devotions when we can sing songs and share our thoughts. I feel like it’s such a big blessing from God that I get to take care of these kids.

“I want to serve Him in any way that I can.”

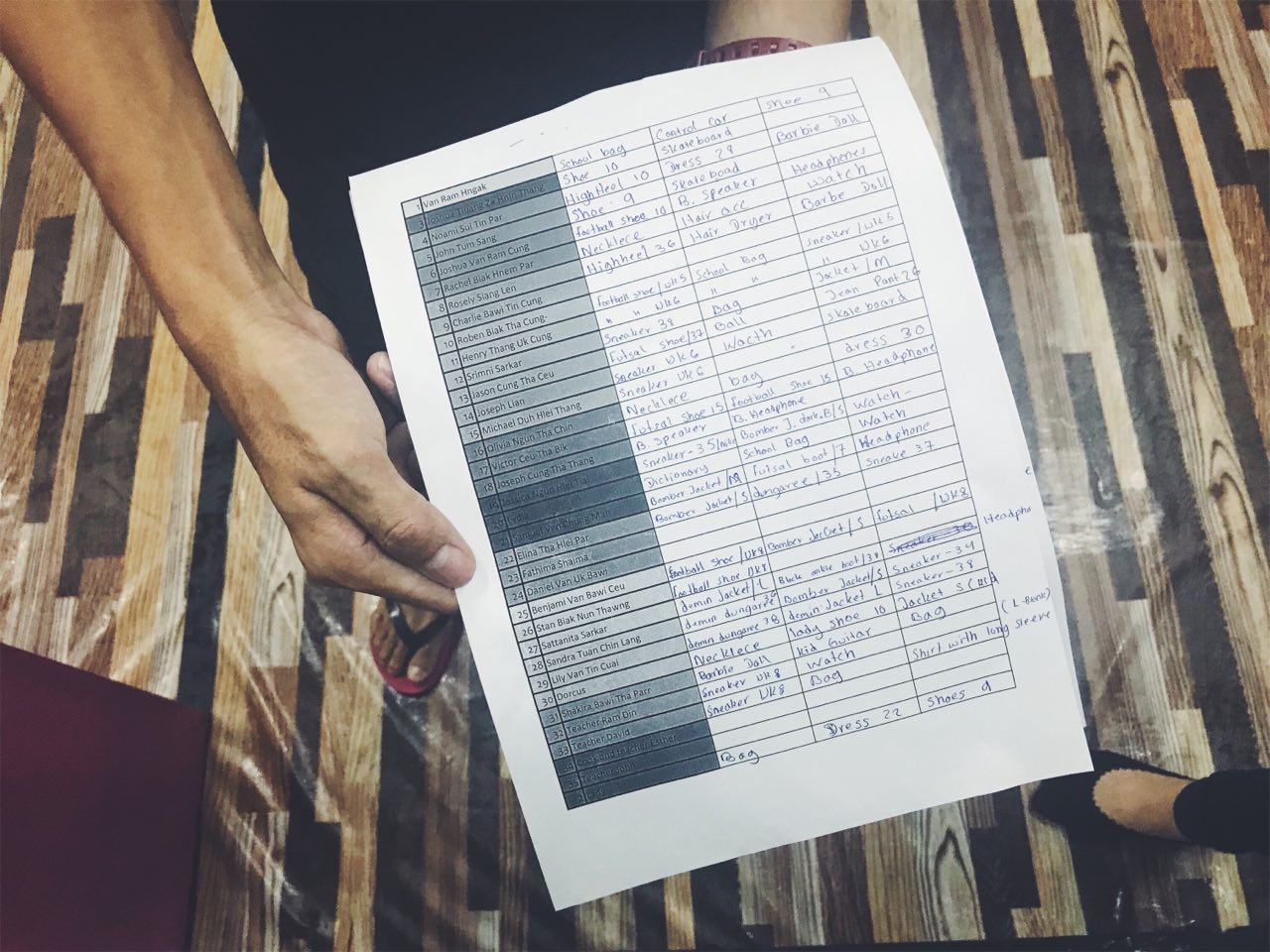

According to John, Christmas is one of the most exciting times for the children at CSO because they can look forward to gifts from donors. View CSO Puchong’s 2018 Christmas wish list here. If you’d like to contribute any items or bless the children in other ways, please drop us an email.

Beyond the season, what the school needs most are more volunteers who can teach the children for at least one semester a year. They also don’t have enough computers to give the kids regular computer lessons, which would furthermore allow for e-learning. For more details on how to help, you can also reach out to John here.