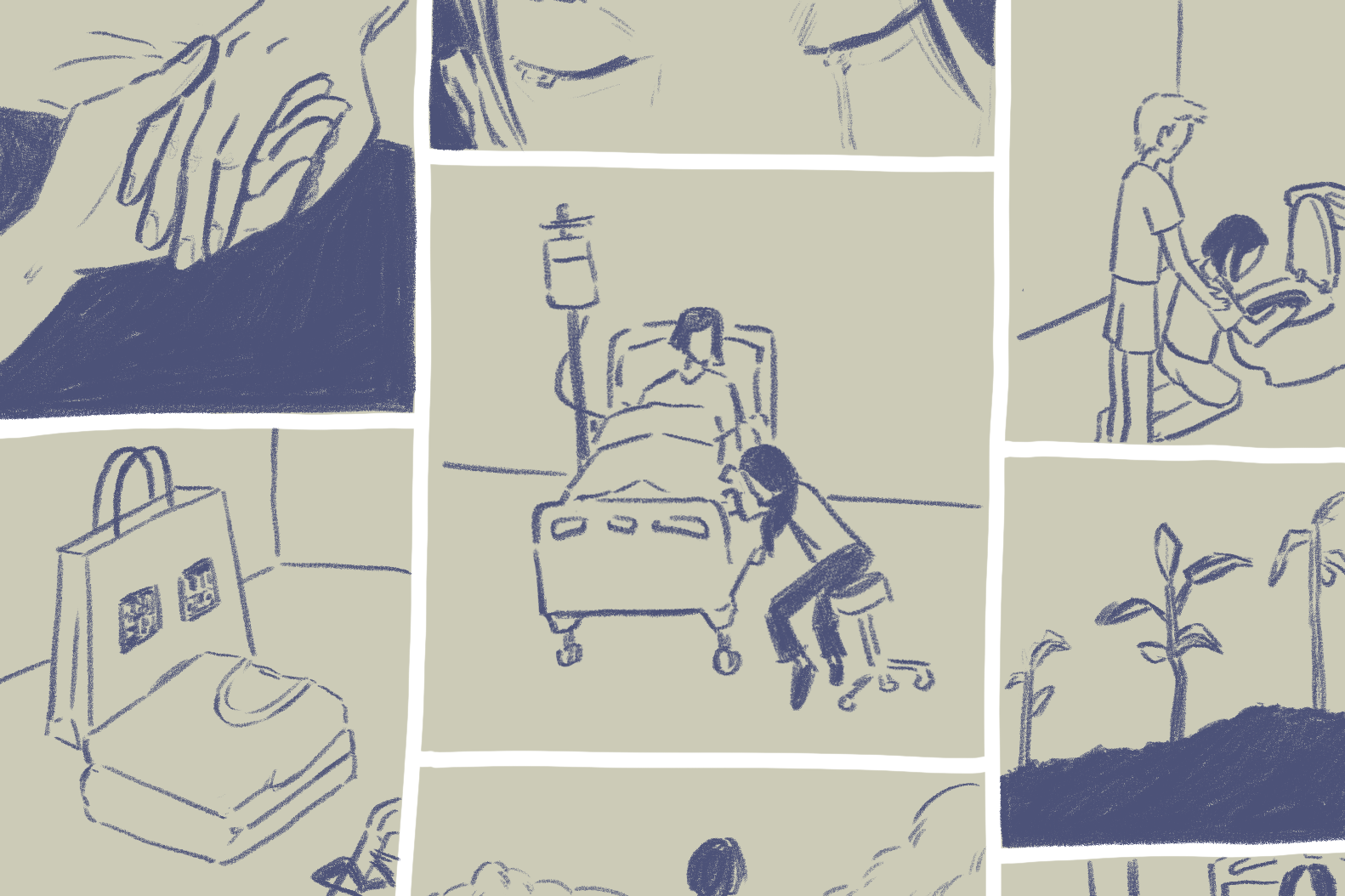

As a junior doctor in her fourth month on the job, death is no stranger to me.

I’ve called families at 3am to let them know that their loved one’s blood pressure is downtrending, that this is a bad sign, and to visit them soon.

I’ve started the palliative care medicines that help to regulate one’s breathing and numb the pain and countless number of times.

I’ve watched the slow burn of cancer eat away at patients, witnessed their deterioration from already frail to barely able to bring a spoon to their mouths, to lying slack-jawed on the hospital bed, their breathing increasingly laboured.

But when my own mother was admitted to the intensive care unit and hospitalised for the tenth and possibly final time, I felt less “doctor” and mostly numb.

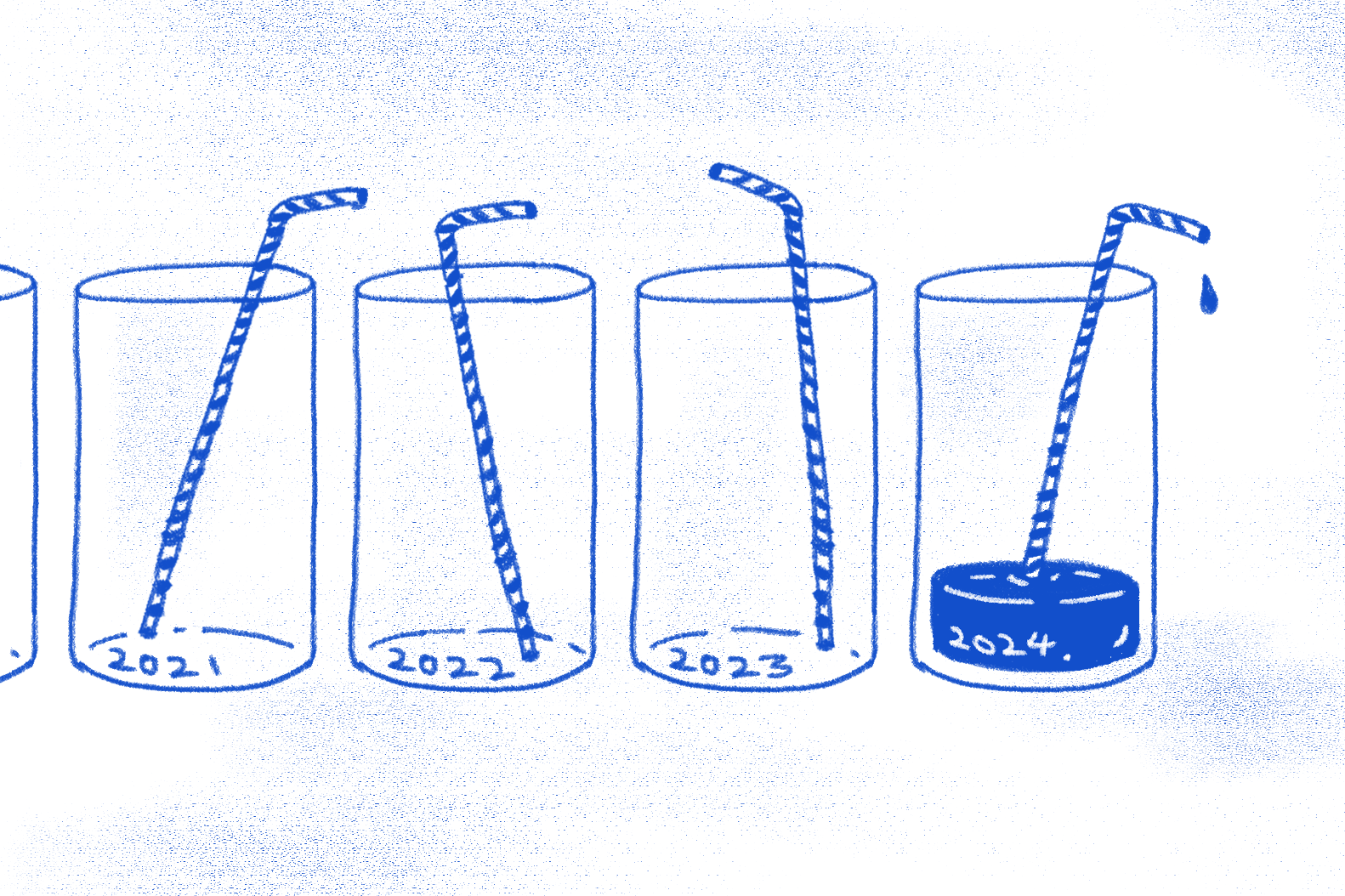

“It’s been four years since your mother was first diagnosed. She has already outlived the statistics. We need to be honest about her prognosis,” the doctor said.

A week before my medical school graduation ceremony, my mother was hospitalised for malignant bowel obstruction, a common complication in patients with terminal bowel cancer.

While I was sound asleep post night-shift, my mother began retching into the toilet bowl. My father, not wanting to disturb me, quickly brought her to the hospital after.

While the scan showed an obstruction possibly amenable to surgery, my mum adamantly refused. “I’m tired enough as it is, I don’t want to go under the knife anymore,” she said, her smile tight as she clenched the hospital bed frame.

Diagnosed with cancer at a young age, she discovered the love of God through kindness and open doors

Over the next few days, different doctors came in to give their opinions.

One doctor suggested starting morphine. I knew what this meant.

“There’s no point anymore. The cancer has spread everywhere,” he said to me in confidence, not unkindly.

… just a week before she was hospitalised, she had excitedly requested to head to Uniqlo to buy new clothes to attend my graduation.

It was a week before my graduation ceremony. I was torn between wanting my mum to see me graduate and relieving her of her suffering. In a way, I didn’t know what to pray for, anymore.

Later, I learned that just a week before she was hospitalised, she had excitedly requested to head to Uniqlo to buy new clothes to attend my graduation.

I couldn’t help but tear, thinking about the freshly washed shirt and pants that lay unworn in the closet.

“I think it would be better to just pass. I pray God will be merciful,” my mother said one day.

In the face of terminal illness, does one pray for a quick death or miraculous healing? Does one sit tight and let God’s will prevail? Does one surrender and stop praying altogether?

These questions swirled through my mind for days. I thought about it every morning as I put up my ward round notes, for the happy patients who would be discharged well and stable, to the sick ones I was discharging to a hospice.

The internet offered little advice for this. I learnt a lot about what one should do after a loved one passes — grief and all its five stages, how the Lord is close to the broken-hearted and those crushed in spirit.

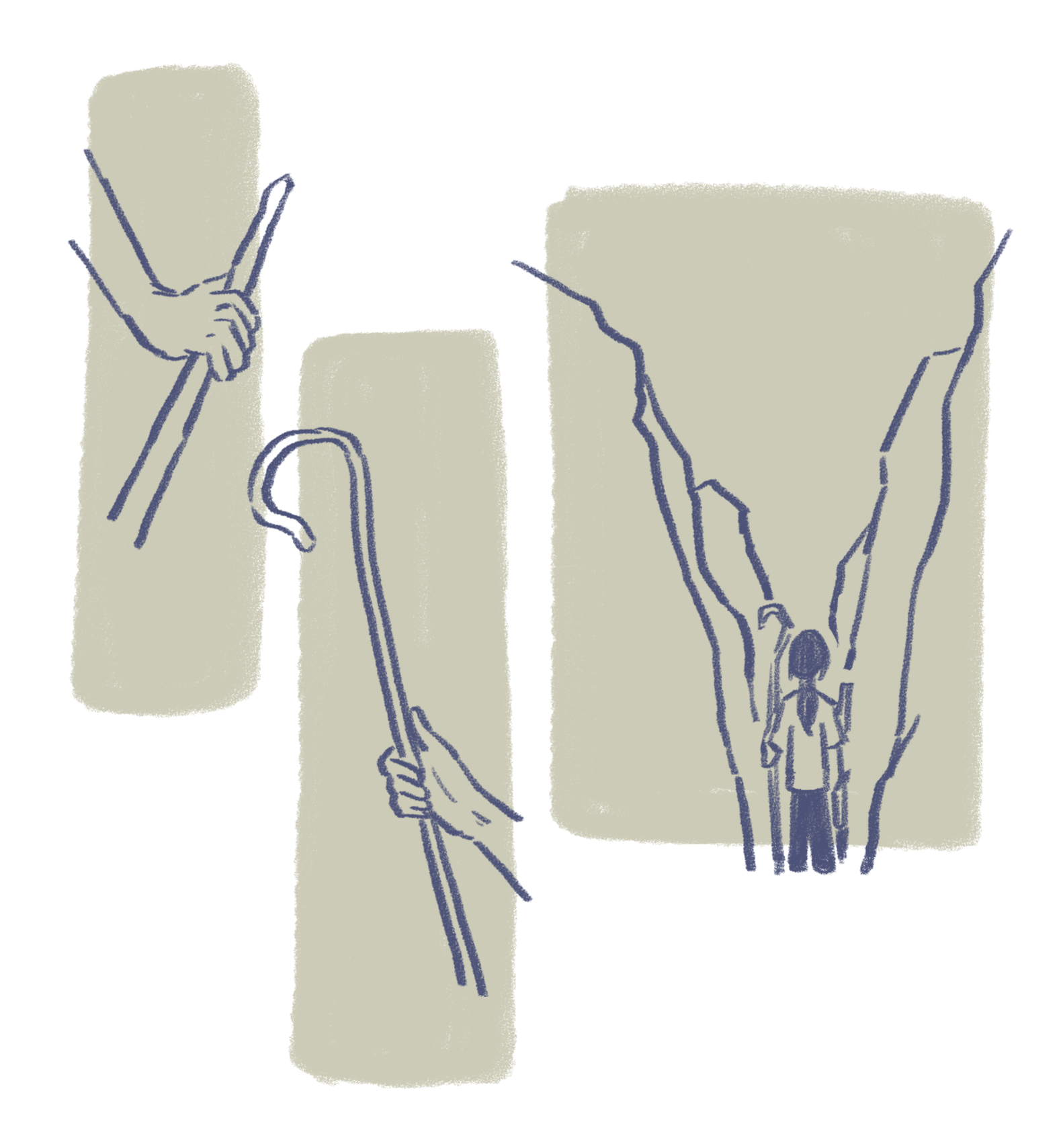

But was it wrong to pray that my mum’s suffering would end, and soon? It felt like we were stuck on a cliff and in perpetual high-alert, an invisible wall pushing us towards a slow and inevitable end.

I remember sitting with my mum in tears while my grandmother clung to life.

“It would be much better for her to pass, look at how much she’s suffering,” my mother told me, her face in her hands.

I knew grieving and loss would be difficult, but in a way, the teeter-totter of the moments preceding it — perhaps this was worse.

However, I eventually learnt that I was asking the wrong questions.

As strange as it sounds, I’m learning that dying is a process. And while we might have many questions, some answers will only be revealed when we get to heaven.

While it is often considered taboo to discuss death, to the point that some boycott particular numbers in Chinese culture, the Bible does not shy away from the realities of death, or the moments that surround it.

Indeed, mortality is a crucial part of the human experience. Ecclesiastes 3:1-2 tells us that death comes to all of us: “To everything there is a season, and a time for every purpose under heaven: a time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted.

I’m wondering if this is what it means to be a Christian. To look death in the eye and see the Saviour’s hands reaching forth.

“For we know that if our earthly house, this tent, is destroyed, we have a building from God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens.” (2 Corinthians 5:1)

In this season, Romans 8:38 has spoken deeply to me.

I am persuaded that neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.

Nothing can separate us from the love of Christ.

Romans 14:8 shares another truth: “For if we live, we live to the Lord; and if we die, we die to the Lord. Therefore, whether we live or die, we are the Lord’s.”

Whether we live or die, we are the Lord’s. That in the moment where breath becomes air, death is no blanketing darkness but unabated light.

John 11:25-26 says it all too plainly: “He who believes in Me, though he may die, he shall live. And whoever lives and believes in Me shall never die. Do you believe this?”

Do we believe this? I’m learning to.

As I write this, I’m planning for dinner with my mum. We’re having ramen, one of her favourite dishes. She’s on antibiotics and indefinite morphine for now.

We both know that we don’t have much time left, but I am learning to treasure the time I do have, rather than the moments I don’t. Mother might be alive, but even when she passes on, I know that she will be with the Lord.

In every moment, I am learning to cherish them and trust in a God who loves and cares for my mum (and me!) more than I ever could.

As Psalms 23:4 tells us: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil; For You are with me; Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me.”

In Elizabeth Elliot’s words, Christ’s story never ends in ashes.