“Why would you choose to be a missionary? Are you stupid?”

When Lue Maiseka announced that he was going to work as a Bible translator, his family and friends did not take it well. He was 27 years old then.

His colleague Zeto Wekan, did not have it easy as well. The comments he received were mostly negative. He was chided for not thinking about his future. He was berated for following orders blindly, without a mind of his own. Many asked him why he did not become a government employee – a respectable, legitimate job.

They warned him: “In the future, you’ll be left floating, high and dry.”

Lue and Zeto turned a deaf ear to the criticism and persisted in their work. But the words continued to ring in their ears, and both admitted that on bad days, they had thoughts of throwing in the towel. The temptation was strongest when they saw others going to university, or working for the government.

But they persisted.

“I told the critics, this is what I feel should do,” said Lue. “Let’s see what the future bring, whether this work will kill me or provide for me. None of us know what the future will bring.”

GOING OUT WITH A BANG

In July 2016, Thir.st caught a glimpse of this “future” when we attended a Bible Dedication Ceremony in Pulau Fordata — located in Tanimbar Islands of Maluku province, Indonesia.

The village people were celebrating the complete translation and publication of the New Testament. This was the very first time a complete Testament from the Bible had been translated into the people’s local language.

There were traditional dance performances, a full trumpet band, and fireworks – always a favourite, anywhere on earth – to end the night. When the ceremony ended, I caught up with a very busy Zeto, who was also the ceremony coordinator. His face was a mix of fluster, relief and inexplicable joy — to see the fruits after many years of labour.

“I just want to say, ‘Thank you, God.’ He helped me and my translation team for a long time.”

BIBLE TRANSLATION: “A SLOW, LONG WALK”

Translating the Bible into an isolated local language is a process of many stages, over many decades, under system honed by the Wycliffe Global Alliance (Asia-Pacific).

Fordata locals such as Lue and Zeto act as Mother Tongue Translators, study the national language Bible and a number of translation resources to help them translate the Scriptural text into the local language.

Then there are Other Tongue Translators (OTTs) – cross-cultural workers who play a crucial role in checking local translations against English, Greek, Hebrew and a number of other resources, ensuring that the meaning is accurate. This comes at a cost: OTT’s must embed themselves among the local population for years to familiarize themselves with the local language and culture.

The translated passages and verses are then relayed to the locals to gauge their accuracy, in a process called community testing. The missionaries next carry out thorough verse-by-verse checking several times, before bringing in an outside consultant for extra eyes and to ensure accuracy.

A final community testing and several rounds of revisions later — and the New Testament is finally compiled, in full, for the first time, in a land that would previously only have heard of the Bible in a foreign tongue. The Word of God, finally revealed in full in a localised, culturally relevant form.

LET THERE BE LIGHT

In Fordata, that whole process took Sarah and Craig Marshall 25 years.

The Marshalls, who are Bible translators and missionaries from Wycliffe Global Alliance (Asia-Pacific), moved from the United States to Indonesia in 1988. They came with the aim of helping the people of Fordata deepen their understanding of God. Craig described the entire process as “a long, slow walk in the same direction”.

“Translations don’t happen overnight,” he told Thir.st ahead of the Bible Dedication Ceremony.

There was a need for a translated Bible as the Fordata people had been reading Scripture in the national language, Bahasa Indonesia — vastly different from the Fordata language — ever since Christianity had been introduced in the early 1900s through Dutch Reformed and Catholic missionaries.

Nobody in the Fordata church congregation actually understands the national language very well, said Mother Tongue Translator De Elath, who worked with the Marshalls for 10 years.

“Bahasa Indonesia, as compared to the local language, is a very formal language. People told me, ‘It would be so good if we could have the Word of God in our language.’”

The lack of teaching material, coupled with the lack of understanding of Bahasa Indonesia, had led to “a very weak church”, according to the Marshalls.

“Becoming Christian and following Jesus can be two completely different things. Most Fordata are religious and would say they are Christian, but actions and words can be a different story,” said Craig.

For example, many Fordata cling on to traditional animistic beliefs, or what Sarah calls “fears” — specifically spirits that will do harm to people. De Elath said many Fordata locals are afraid to enter the jungles due to such taboos.

“People will say, let’s not take our children to the jungle because there are evil spirits that will surprise them,” she explained.

However, having the New Testament in Fordata language has resulted in a slow but visible change. Many amulets and objects of witchcraft, such as fossilised roots, have been removed from homes and buried.

“Now, people have read about God so they just go to the jungle with their children. They aren’t thinking about the taboos and they don’t worry about it,” De said. “Some people even take their children and sleep two or three nights in the jungle and then come back to the village.”

Added Sarah: “As people become aware of the greatness of God and the power that we have because of Jesus, they are set free from those fears. And it’s a wonderful thing to see people being set free.”

WORK THAT TRANSLATES INTO TRANSFORMATION

Perhaps the most marked transformations were observed among the Bible translators themselves, given the sheer number of hours they spent poring over the Bible.

The impact of the Bible on his life has been “huge”, said Lue.

“Before, I used to use terrible language. I swore a lot. I fought a lot with other people, I really didn’t care. But when I was translating the Bible, the words convicted me because they completely explained my way of life,” he said.

“It was to the point where I couldn’t translate at times. I just sat there thinking, wow. These words are pointing out my sins.”

Zeto, a father of two children, said that “spectacular things” have happened ever since he took on the job as a Bible translator.

“My salary may be limited, but there was enough money for us to live. We didn’t ask for food from other people, but people came to us asking for help from us,” the 29-year-old said. “That strengthened me and my faith, and I saw before me — our needs for food, a place to live, the future — were all met.”

Despite the disapproval he had to deal with in the beginning, he is now convinced that God is a provider and his part is to simply work as long as he has the opportunity to do so.

The journey to publishing the New Testament was also exceptionally tough for the Marshalls. Not only did they need to assimilate into an entirely different culture and learn its language, they also brought up four children in Fordata.

Sarah choked up as she recounted the near-death experiences they experienced as a family. Once, her son Caleb, was so sick with malaria that “he really could have gone”.

“He was a skinny 10 year old who was so incredibly sick. But God provided. He intervened and spared him. It’s been an amazing journey to see God take care of us. God is really enough,” she said.

“So that’s why we keep going. Seeing the people read the Scriptures in their language and recognising the hope we have because of Jesus.”

“It makes those days when we were really sick worth it.”

A WORK THAT NEVER ENDS

But for all the years that needs to be put into the process, and all of the lives uprooted, the most crucial stage of Bible translations actually comes after the fact – once the Bible is translated and put into the hands of believers. There is no use having a physical copy of the Bible and not using it, the translators said.

“We need to read the Bible and reflect individually what it is saying to each of us,” said De Elath. “We can’t take this Bible, just lay it on the table and never read it.”

“When we read it, we need to ask ourselves: Is this true with my life? Am I refusing to do this in my life? This is how we should use the Bible, now that we have it in our language.”

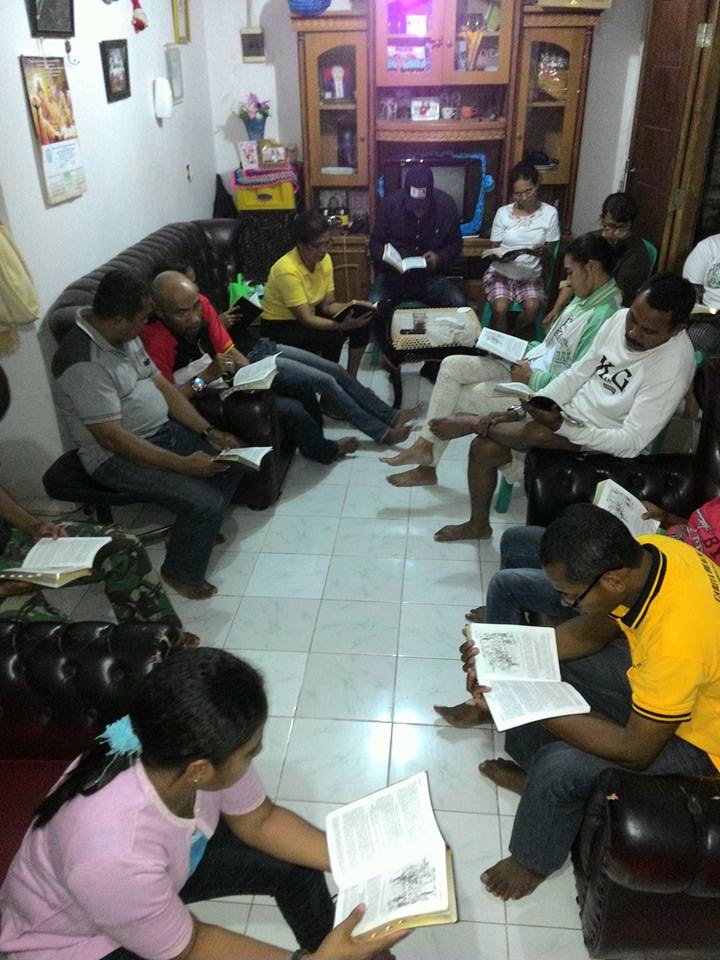

The churches in Pulau Fordata had already begun to use the New Testament in sermons and Bible study groups. Lue observed that most people, the church congregation and the government included, are in favour of Bible translation. Having the New Testament has even revived and encouraged local language use.

“Hear a church leader preach in Fordata, even if it’s only a little bit, is much more meaningful than lots of words being spoken in the national language,” he added. “It’s really satisfying spiritual food.”

After the Bible Dedication Ceremony, the translation team got up bright and early the next day to distribute freshly-printed copies of the Bible to the Fordata people. They are sold at 25,000 Indonesian Rupiah (around $2.50 in Singapore) per copy, and copies are also being distributed to other villages in the Tanimbar islands.

The translation work does not end here – there is still the entire Old Testament to work on, after all. Work on the book of Genesis is already underway, and the local church has requested for the Marshalls to translate the book of Psalms and Proverbs. I mentioned to Sarah that at this rate, she probably would not be heading back to the US anytime soon.

She laughed and said: “Yeah, these people really gotten to us and look, they love us. They’ve accepted us as their own.”

“And that’s a pretty amazing thing.”

To find out more about the work of Wycliffe and how you can serve as a Bible translator, visit www.wycliffe.org.