I stared at the rows of bottles in the room Marina had ushered me into. I’d been awestruck by the sights in New Zealand over the past few weeks, but nothing could prepare me for this.

In the jars were hundreds, if not thousands, of buttons. In any other setting they would have been an impressive collector’s item, but I knew I stood before something a lot more sacred.

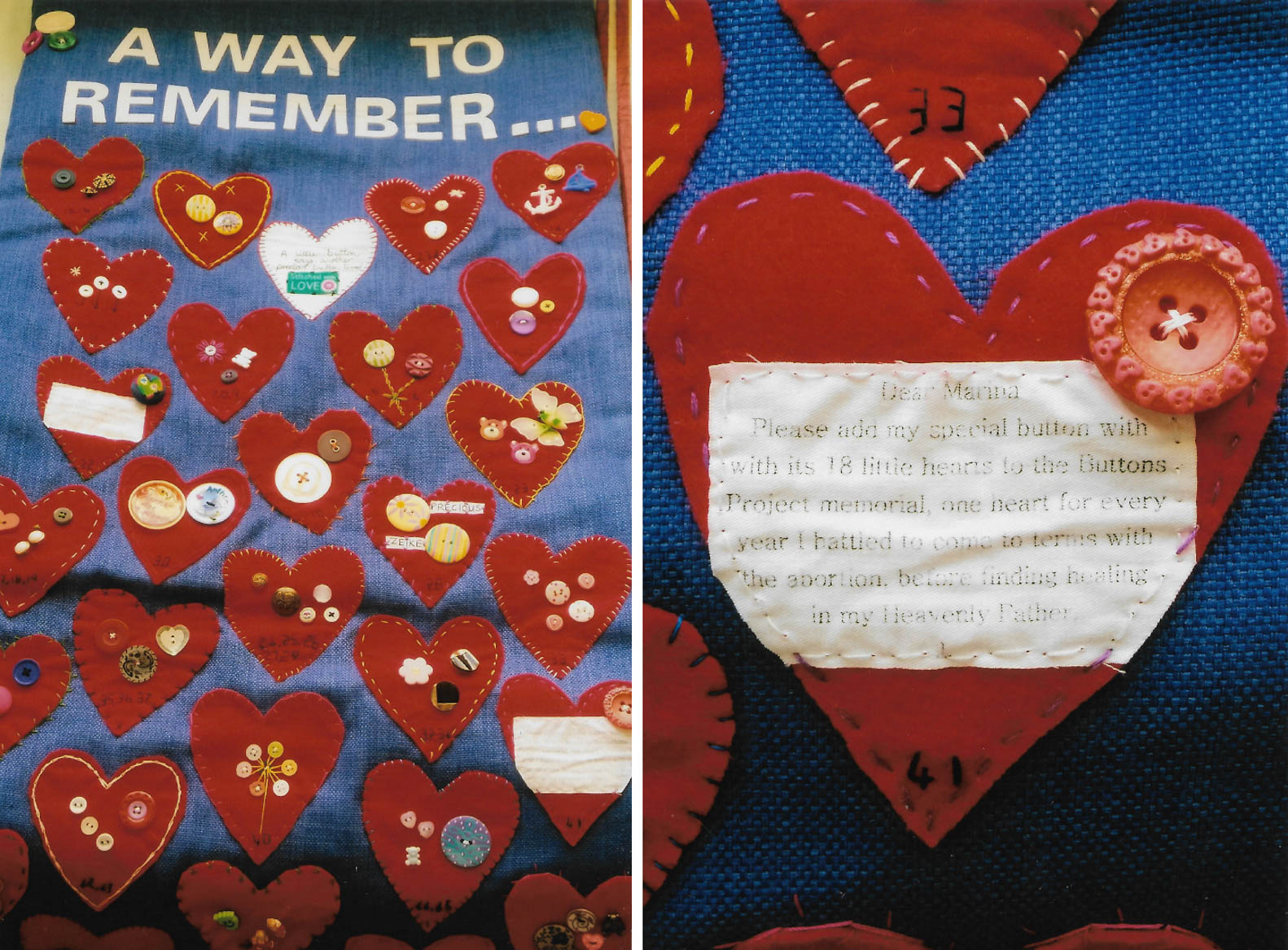

Every button represented a baby lost to abortion, sent in by those who mourned to Marina Young, founder of the Buttons Project.

“Through my own abortion experience I came to realise many women feel the same – that it can be difficult to gain any sense of closure. There is no grave to visit, no tangible way of remembering,” Marina shared with me.

“That’s why I started the Buttons Project. To create a memorial for the babies we’ve never met.”

The familiar sadness I’d carried for years inside me stirred. Most of it had healed over and been replaced by a renewed sense of hope – but I would never forget the dark place I’d left behind.

Just like Marina, I too had an abortion in my early 20s. I too had searched for peace, the unknown face of my unborn child etched in my heart like a scar.

It was the greatest irony; I had always wanted my own children as a young girl.

But when the second pink line appeared on the pregnancy stick, indicating I was most likely with child, the only thing I could think of was to erase it immediately – like I’d written something wrong.

Although we’d been dating for some time, my boyfriend was not ready to get married and start a family. We hadn’t considered the possibility of pregnancy.

I could see my father’s crestfallen face. I could imagine how my mother would have chastised me. I told you not to anyhow stay over at people’s house. They wouldn’t know about my ordeal until years later.

My boyfriend and I agreed that the only option was an abortion. To us, this wasn’t our baby. This was our problem. And problems needed to be solved.

Back in school, I’d written impassioned pieces on how I was against abortion, but now abortion wasn’t the only problem. I had a problem. This was the solution.

Everything the pre-abortion counsellor told me flew over my head. Yes, I know the risks. No, I don’t want to reconsider this. Get this out of me so I can move on with my life.

And when it was all over, I walked out of the clinic clutching my bundle of relief. My old life was waiting for me. My relationship was waiting for me. No one would ever have to know.

Problem solved.

But that night, I struggled to sleep; it was more than the physical pain I was in. Somewhere, growing in me, was a new pain where my child had been.

The child I had killed.

Very much like its cousin — shame — guilt is like a tumour. It appears insidiously in a place you cannot quite put a finger on but announces its presence like thunder – throbbing in your head or in your gut.

I couldn’t tell if I was guilty of getting pregnant or terminating the pregnancy or not hesitating to terminate the pregnancy – but within the next few days of the abortion, I was a wreck.

What was happening to me? I’d never even met this child or thought of it as a life, as my own. I was supposed to be the same June as I’d always been, unpregnant, not-yet-a-mother.

This episode was supposed to be a blip on the screen for my boyfriend and I. A small error reversed as quickly as possible. Control-Z. Undo.

So why did I feel like a part of me had died?

My boyfriend was very supportive at first; he was the only one who knew about this. He’d promised that we’d go back to normal once we’d crossed this hurdle, and I believed for a while that we were stronger together after the abortion.

But as the mounting guilt of killing my own baby sapped the colour from my life, the strain on our relationship soon reached its tipping point.

Six months after the abortion, we called it quits and broke up.

The time following the end of our relationship was what I can describe as my own private hell. Depression sunk its ugly teeth into me and along with that came nights of bitter tears. I had never felt so alone, having isolated myself from most of my social groups.

If the topic of abortion ever came up, the enormous tumour of guilt burned inside me. It was easier to avoid conversation altogether.

I felt like the worst of sinners, crying out for comfort yet believing I was undeserving of any. I was grieving the loss of my child, but I was the one who killed him in cold blood.

For more than a year and a half, I cried myself to sleep every night.

It dawned on me gradually that the wound was too deep to heal with time, and I was going to need something stronger – or never stop hurting.

I needed God.

It’d been a long time since I’d attended church regularly. I had stopped all church activity after the abortion, unable to bear the tension of my secret shame.

But now I was desperate. The dark tunnel I’d been walking in was only getting darker. So I asked a friend if I could follow her to church.

I was like the woman in Luke 8:43-48, grabbing onto the border of Jesus’ cloak, believing with all her heart that it was the only chance she had to be healed.

It didn’t happen all at once, but I look back now to see that this was precisely where healing began.

“If you want to walk into your destiny, you need to come to a point where you have nothing to hide, nothing to lose and nothing to prove,” the preacher said.

It had been several months since I’d started coming back to church. I was in a much better place – surrounded by good people, reminded of God’s love for me, ready to believe there were brighter days ahead. And when I heard what the preacher said that morning, I realised I wanted so badly to walk into my God-given destiny, whatever that looked like.

Sure, I had nothing to lose and nothing to prove at this point. But I still had something to hide. Up till now, I had never spoken about the abortion to any of my church friends. Honestly, I was hoping I’d never have to.

But now I knew I had to.

Taking our secret sins out of hiding is very much like coming before God with our confessions. I’m glad you told me, I imagine He’d say, though He’d have known it all along. Now let’s get you out of there.

And that’s just what happened when I finally told my cell group about the abortion. Instead of judgment or disgust, love came pouring forth. It was like a veil had lifted in my relationships.

With my friends’ support, I found the courage to go for Rachel’s Vineyard, a weekend retreat for anyone affected by abortion. The experience of group therapy was terrifying to step into. I remember wanting to run away the moment I entered the retreat centre.

But then I saw all the other women who were spending the weekend together with me, and it hit me: Each of us had lost a child to abortion and was suffering for it.

During one of the group sessions, we were sitting in a circle for an activity. Suddenly the room faded, as though in a dream, and the talking around me dissolved into a faint murmur.

Right in front of me stood a man I somehow recognised to be Jesus, and in his arms was a wiggling, happy boy whose face I could not see clearly.

I sat frozen in my seat, but Jesus walked towards me and placed the child on my lap. Immediately I knew he was the baby I had lost, and a peace I’d never felt before enveloped my heart.

All this while I had been struggling to believe my child was in Heaven; after what I’d done to him, how could he be in a happy place? He should have been bitter and angry at me for denying him life – his own mother! Where is my baby now? I’d cried for so long.

But as I held my son for the first time, I had my answer. With Jesus standing beside me, eyes full of love, I felt all the guilt and longing fall like chains.

I was finally free.

When I found my way to Marina Young’s house in Auckland, New Zealand, I knew God was up to something. I’d quit my job and come to the country as part of my healing journey, unsure of what lay in store.

I had never heard of the Buttons Project previously, but when a pastor I met at a local church heard my story, he immediately referred me to Marina and her husband, Peter.

As a young unmarried couple, Marina and Peter got pregnant before they were ready to settle down. They took the advice of well-meaning friends and family and decided to abort the baby. Although they eventually married and had three children, they never stopped mourning the loss of their first child.

This compelled Marina to start the Buttons Project, to help others who grieve in silence find a place of solace and community. She started the website, which invited anyone affected by abortion to send in a button, either physically or digitally, to create a memorial for babies we’ve not met. To this day, the Youngs have received over 20,000 buttons.

With their blessings, I decided to bring the Buttons Project to Singapore earlier this year, in hopes of helping women and men affected by abortion in our nation take a step towards healing.

If you are on a similar journey, please know that you are not alone. What happened matters. It will always matter.

June first told us about her story 5 years ago, but she is still sharing her testimony today.

You can catch her in person through an Instagram Live on @heartbeatproject.sg this Thursday (March 17, 9.30pm-10.30pm) as she opens up about her abortion experience and her healing journey.

2022 marks the 50th year since the two-child policy was introduced. This Sunday (March 20) will also be the 52nd year since the Abortion Act was passed in Singapore.

Heartbeat Project and Buttons Project Singapore will be collaborating to host 2 events in March. The 2nd is a Support After Abortion Zoom event on Wednesday (March 23, 8.30pm–9.30pm) for anyone who is hurting from the effects of abortion.

In this year of jubilee, they believe that God wants to redeem those who went through an abortion and set them free.

For more details, visit the Heartbeat Project website/Instagram page or Buttons Project Singapore website/Instagram page.