I almost committed suicide in August of 2017. I’d made plans. I’d started to put part of it into action, unbeknown to those closest to me.

I have a loving wife, a couple of good kids, and a supportive extended family. My Bible study group meets at my house every week, and we are a close-knit group. My support mechanisms are in place, and I know what I should do when depression hits, due to an earlier episode.

So why did things go wrong?

My temper had been getting worse day by day, even in the workplace. At home, I found myself over-critical of my boys, and easily tired. I withdrew from many social engagements. I forgot how to be happy. I’m still not sure how much of that was negativity, or how much of that was something else. My moods were often low. The doctors would call my persistent low mood dysthymia.

The stage was set. No one, including me, expected that the crash would happen.

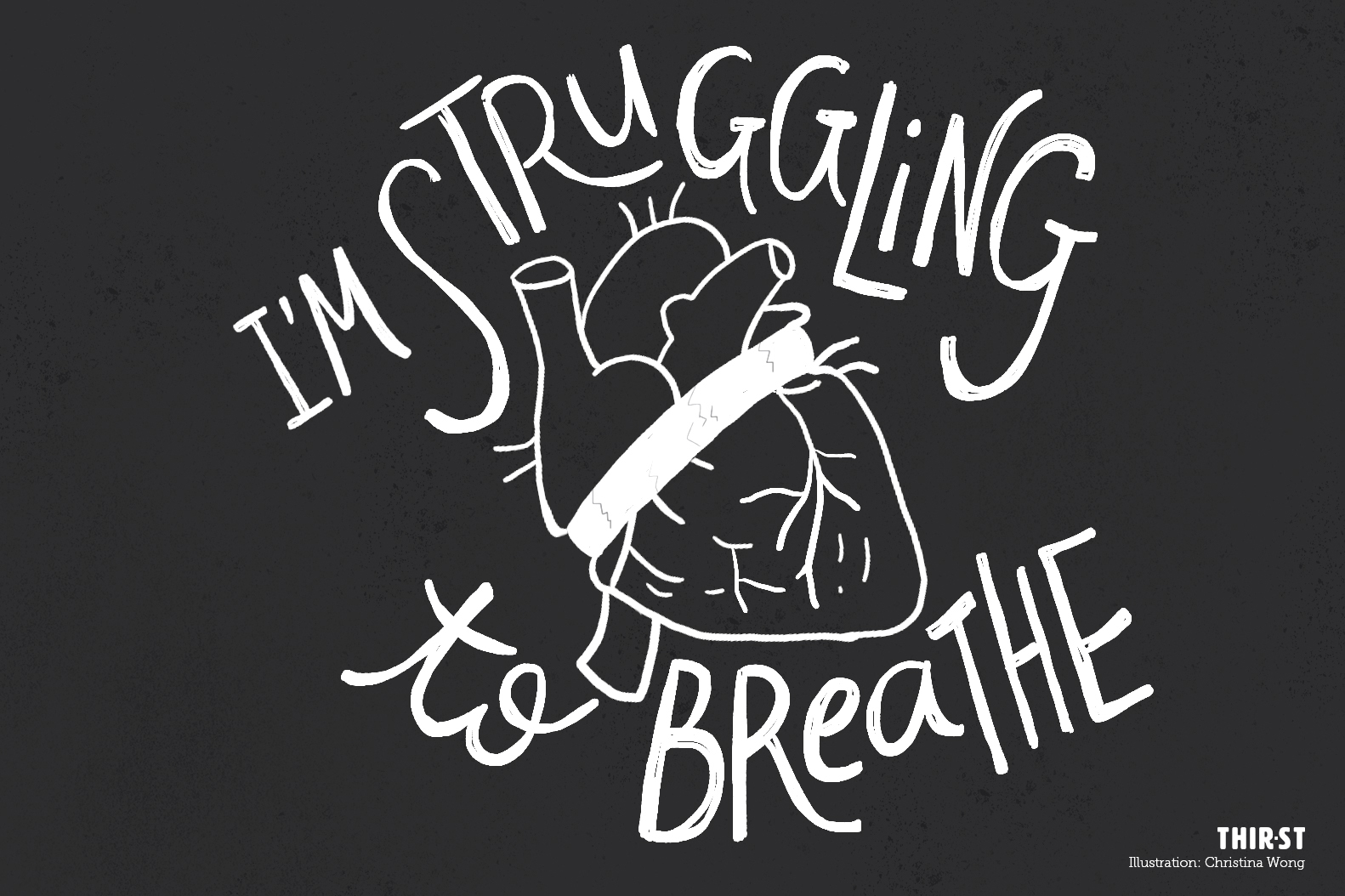

Depression is a reality, and pain can lead us down paths we never knew existed. Let me try to give an idea of how depression feels.

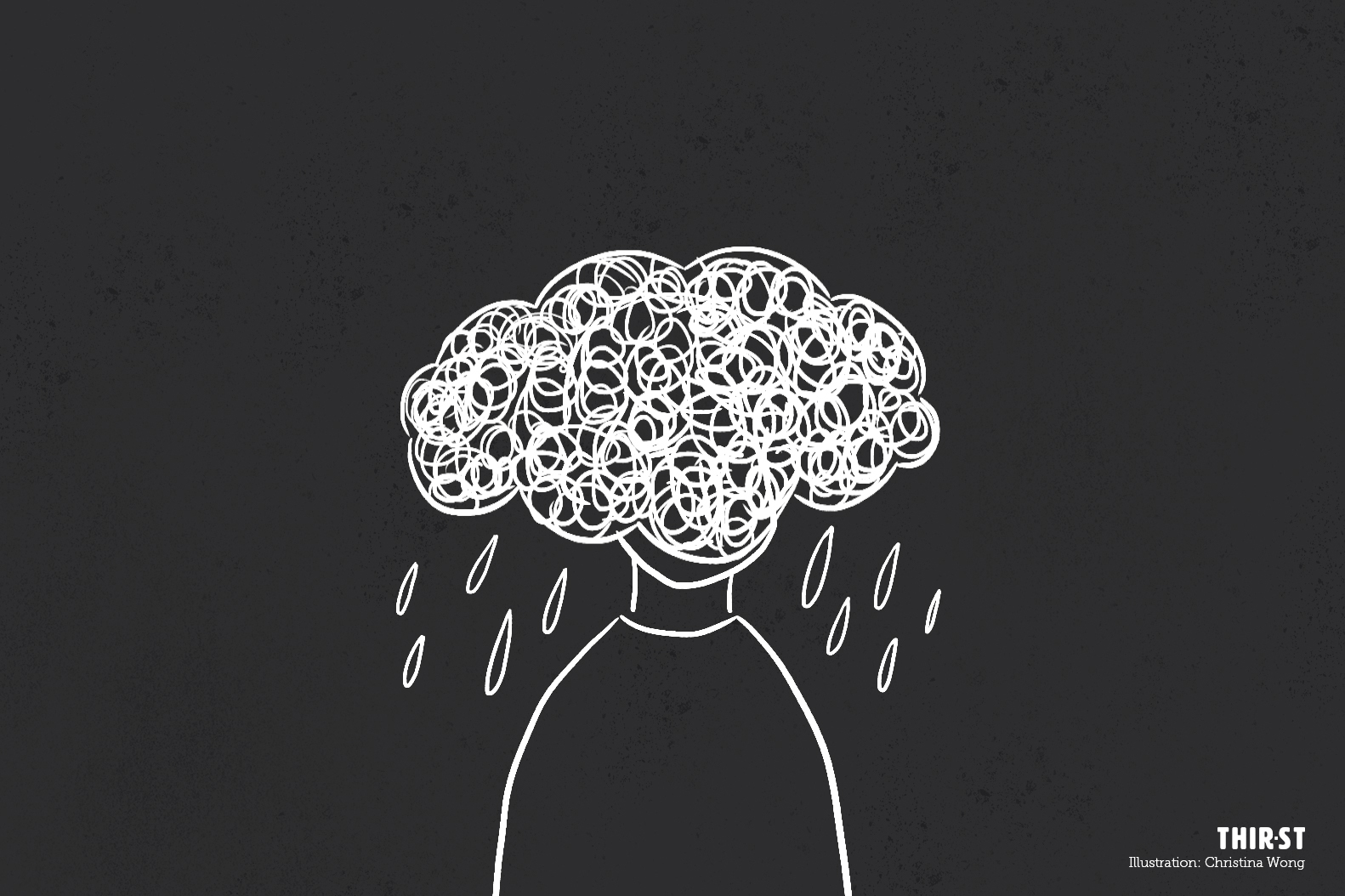

Picture yourself putting on something that wraps itself around the top of your skull. Attached to this is a chainmail veil that drops over your eyes and ears. At the same time, a steel band is put around your heart, and starts to constrict, just a little, even as a cape of liquid metal drapes itself on your shoulders. It’s not heavy, but the weight is definitely felt. None of these can be taken off at will.

Now everything that you see and hear is filtered through this haze. All positivity is filtered out, through your eyes and ears. Pleasure is taken away, and whatever you see, touch, taste, hear, is now tinged with grey negativity. It’s never totally black. It’s a drip torture, little by little. You start losing touch with the world.

If this change was sudden, it might be easier since you know for sure you need help. Instead it drips on you, little by little, giving hope that things may improve, even as it takes away hope.

The band around your heart grows tighter. Everyday, the cape drags down further, gradually. It becomes harder to breathe, and every day grows dimmer, as you drag your feet, as you try to carry on. Soon, you can no longer lift your head. Everything feels like you’re slogging through mud. Drink tastes dry, and food tastes like sand.

Occasional bursts of enjoyment gets through, but nothing lasts beyond that sparkle of time, which makes it even more painful because you can’t reach back for it.

Despair starts to set in. Your self-worth drops. Hopelessness is your constant companion, as pain wracks your heart. Breathing becomes ever more difficult, and death itself seems like a good way out. It doesn’t matter how positive life is for you. Every step is painful, and everything is gray with despair. Every blessing becomes pale, every good thing becomes a shadow that you desperately wish to taste and enjoy, but can’t.

Words matter at this point. Words that tell you that you’re worth something; that someone cares. If you don’t even have that, suicide becomes a reality to dance with. Even with support, death becomes delicious, something to savour, because the pain is so deep that nothing else can fill your heart. As the pall continues to grow, as you struggle to breathe, to walk, to think, nothing matters anymore.

That is how depression feels for a sufferer.

I won’t publish my plan, so that others won’t get an idea of how I planned to end my life. But it had been well thought out. When I reached home that day, I knew how I was going to do it.

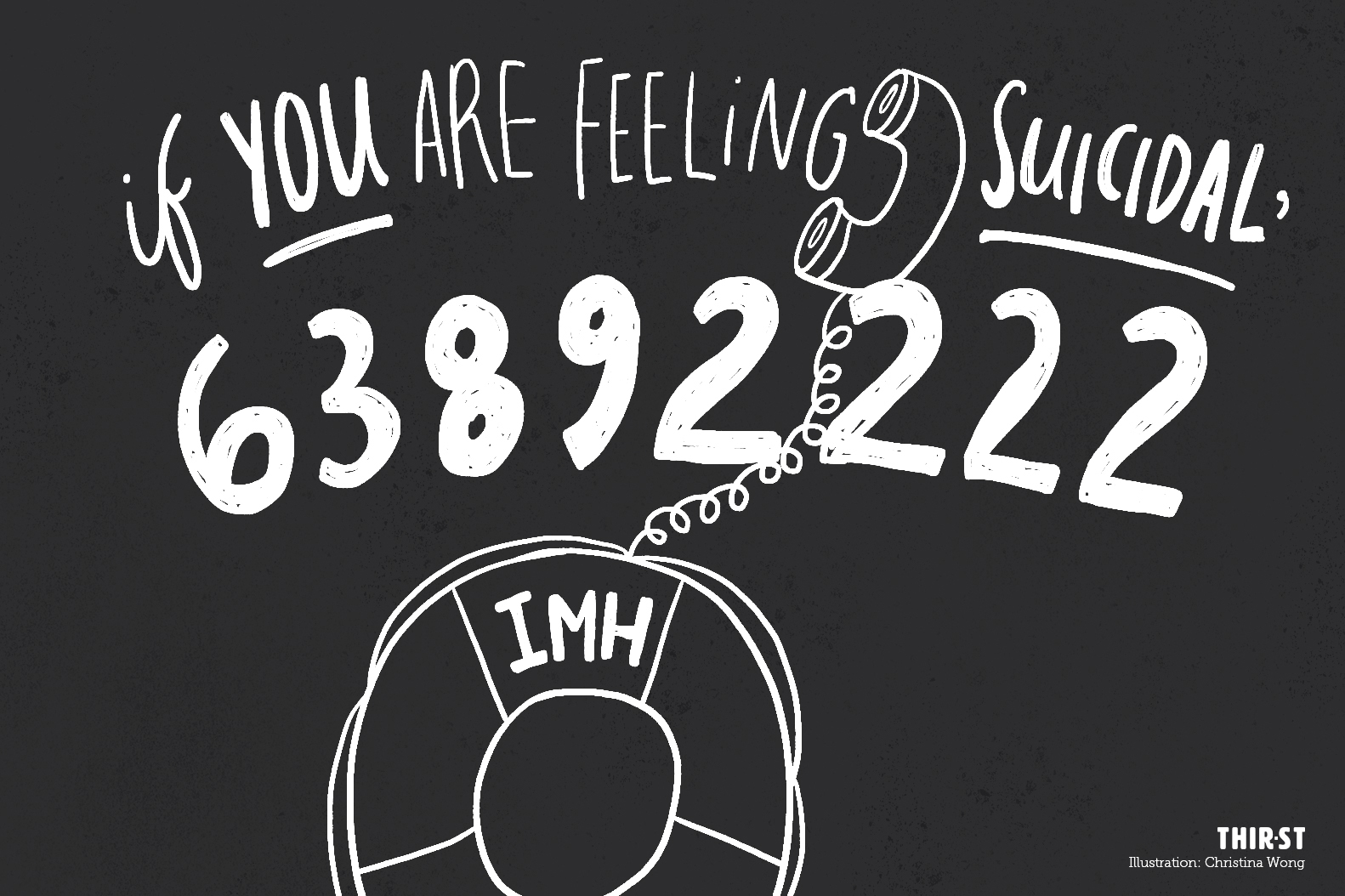

Yet, I promised myself – God’s grace upon me! – to call the Institute of Mental Health’s emergency helpline. If no one picked up, or I got disconnected, I would proceed as I’d planned.

I held the phone for 10 minutes. The counsellors were busy. When someone finally answered, I kept my word. I spoke. She listened. She asked. She advised me to come in to the IMH emergency clinic as soon as possible. She gave me directions, and made sure that I knew their number, so that along the way, I could call if I was in danger. I told her I would.

She had no idea that she was instrumental in saving my life.

I was admitted to IMH for my suicidal plans and tendencies. The time there wasn’t always easy, though everything was regulated and I was well taken care of. There were group therapy sessions in the ward I was in, and I responded well to medication. I was discharged after a week; other patients usually stay for at least a few weeks.

If my story speaks to you in any way, to your current struggles or past feelings, please know this: You are not alone, and help is available.

If you have never sought medical help before, please consider it. There are various means that you can use in Singapore.

If you are not having suicidal thoughts, or don’t believe that you will act on your thoughts in the short run, visit a government polyclinic to get assessed. GPs in Singapore are generally well equipped to assess such conditions. I have managed to get compassionate help from my private GP as well as a polyclinic GP. They will refer you to any government hospital specialist if there is a need.

There are also other sources that you can seek for help from, such as counselling centers, or private therapists.

If you are already seeking medical help, remember that you are not alone. There are many people who are also seeking medical help for mental issues. Don’t feel ashamed, or fall for the fallacy that if you are mentally ill, you are mentally weak. No one chooses to be ill, just as no one chooses to have a broken arm, or the flu. Don’t blame yourself.

Be responsible in taking your medication, and keeping up with your follow-ups – that is already a huge thing. Be responsible for your own actions, and apologise where you need to, but don’t apologise for being sick.

If you feel suicidal, answer the following questions:

- Do you have constant thoughts of suicide?

- Do you have a plan on how to commit suicide? Can you describe it to some level of detail?

- Do you have a timeline by which you wish to commit suicide?

If your answer is yes to any/all the questions above, seek immediate help. Death may seem to be the only option, and may seem delicious and easier – but your mind is lying to you. There are other ways out, and you need to seek help.

Call the Samaritans of Singapore at 1800-221 4444. Alternatively, IMH has a 24 hour helpline at 6389 2222. Both numbers are manned by trained volunteers or counsellors around the clock. Why not talk to someone who is willing to listen to you before you do anything? You have nothing to lose by calling either of these numbers as soon as possible.

There are major changes that mental health sufferers will have to adapt to. Our expectations of life and the world need to be toned down. Get well first. As long as we are not well, there are fights we cannot fight. When we are better, we can then educate others on the illness, and increase awareness of the issue.

Our fight is simply to live to the next day. When we have accomplished that, we can fight for the next week. When we have conquered thinking a week ahead, we can then learn to fight a month ahead.

Don’t expect too much of yourself, because your mind needs to recover and heal. Sometimes the healing can take years. Sometimes miracles happen, and healing is quicker. If not, don’t forget that such mental illnesses are there for the long haul.

If you find yourself dipping back into the darkness, try not to despair. Talk to your mental health professional at the closest possible opportunity. Work with your doctor or therapist, not against them. Pharmaceutical conspiracies are precisely that – conspiracies. The amounts we pay for our medicines, especially at government hospitals, don’t justify the doctors keeping us on treatment for longer than necessary.

Our doctors and therapists work hard to help us get better. If you are not comfortable with the doctor or therapist working with you, by all means, ask for another one. Just don’t do that too often, as there aren’t that many in Singapore to go around!

Get a support group that understands you without demanding more from you. Support groups can include friends, family members or members of your religious group. We need to grow and heal at our own pace, and no one has a right to dictate the pace for us. Our actions will determine how much we progress through therapy and medication.

If we are not honest with our support groups, or our doctors, we can’t expect to get better any time soon. If we are honest and responsible, reaching out for help when we need it, there is every hope and chance that we will come out from under this dark cloud at some point.

Singapore remains a country where depression and similar mental conditions remain not well understood. The medical help structure however, is robust, and has contributed to saving lives. Don’t waste our lives or hurt the ones who love us, by taking our lives into our own hands. Seek help, and remember that we are never alone in this fight. At least you now know that I’ll be struggling alongside you!

This blogpost was first published on the author’s own blog. It has been edited for length and republished with permission.