“Stop trying to ‘heal’ me.”

Recently a friend shared with me this article by Damon Rose, a blind journalist who wrote about his experiences of being regularly approached by Christians who insist on praying for him despite his refusals.

“While they may be well-intentioned, these encounters often leave me feeling judged as faulty and in need of repair,” he wrote.

Rose also interviewed Christians with disabilities who expressed similar sentiments. Some avoid prayers for healing because they find it disempowering.

- I don’t need to be fixed.

- I don’t want to be pitied.

- I hope that I’ll still be disabled in heaven so that I can truly be me.

Those were some of the arguments that stood out for me. I agree that forcing prayers (or anything) on someone is disrespectful and insensitive. But the article also seems to normalise and even hint at glorifying disabilities.

Is that really how self-acceptance looks like?

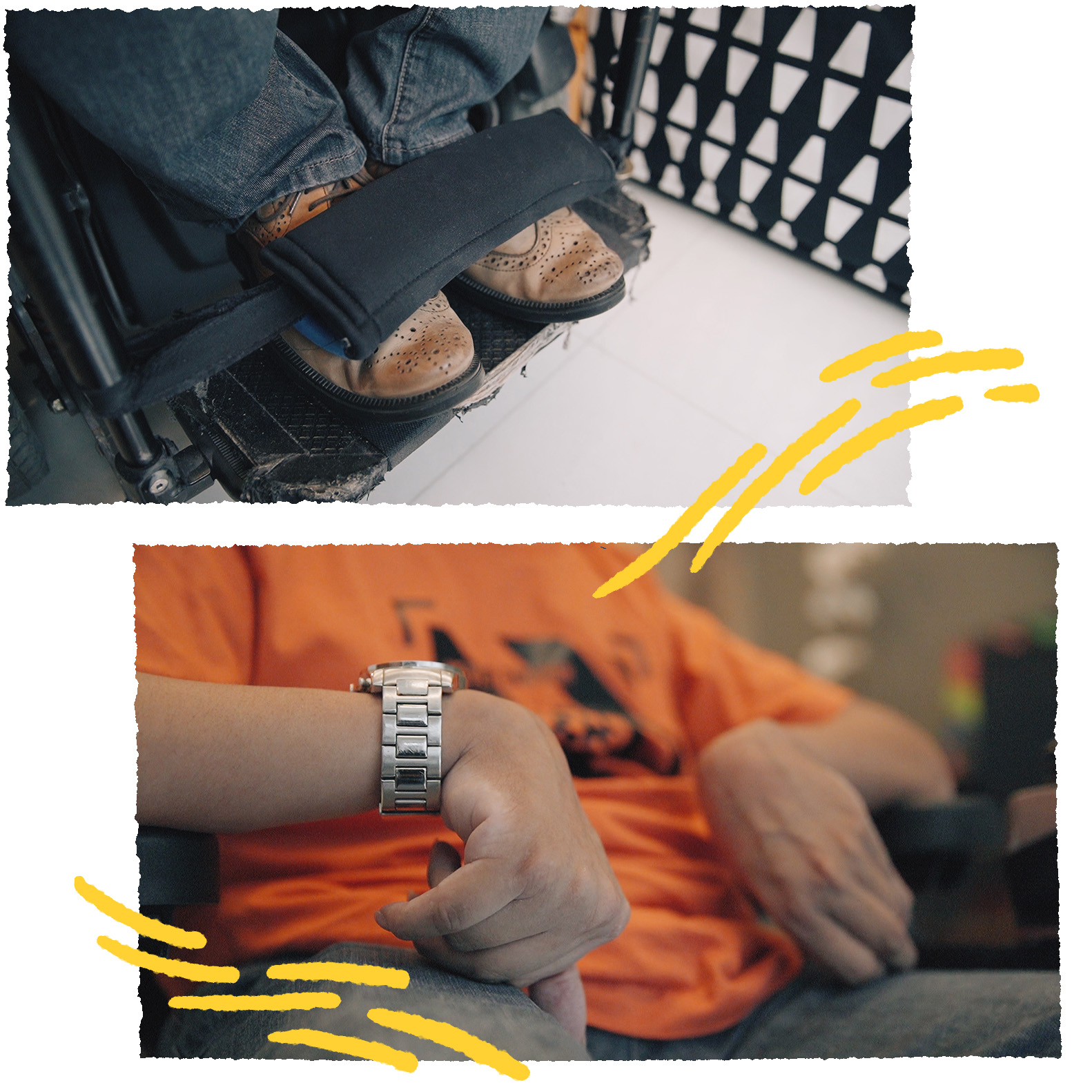

This thought remained at the back of my mind as I meet Alister Ong a few days later. Born with cerebral palsy, a condition where an abnormality in the brain affects a person’s ability to control his muscles, Alister has faced many challenges on a daily basis for the past 26 years of his life.

“Growing up, I couldn’t walk or run,” he begins. “Even if I want to open a bag of potato chips, I cannot open it myself.”

Because of his disability, Alister also couldn’t participate in many activities with his friends, which made him feel left out. During recess, he wouldn’t be able to join his friends to play and often had to sit by himself. His helper would also be waiting for him to bring him home immediately after school.

The lack of social interaction also meant that Alister didn’t have the necessary social skills to make friends. He tried to join in and have conversations with his peers many times, but he never really felt like he belonged.

“Even when I’m together with them, they would usually not take notice of me,” Alister tells me.

“It made me feel like my life is just a passing wind,” he pauses. “I am just so transparent that nobody takes note of me at all.”

This began a cycle of self-pity and self-isolation that would last for years. Alister describes being resigned to a “life of misery” and “being all alone”.

Alister shares that thoughts like these constantly flooded his mind: “Why am I different from others? Is it because I’m like this that nobody wants me? Can I even live a normal life? Get a job and provide for myself? Is there hope? Is there a future?”

“I knew that the only way out for me was to stop the negative train of thoughts from continuing,” he admits. “But I just couldn’t get out of it. Somehow it just felt so comfortable.

“The feeling inside of me was too void, too dark, too empty.”

LEARNING ABOUT LOVE

While he was born into a Christian family, Christianity didn’t mean anything to Alister when he was younger. It was his parents’ religion, not his. But as he faced rejection from others and himself, Alister grew desperate for unconditional love.

“In my lowest moments, with all the feelings of rejection and low self-esteem, there was nobody else I could turn to but God.”

Alister’s attempt to find God drove him to a different church from the one his parents were attending, one which was located on the other side of Singapore at that point in time.

“Take the MRT can get seasick one leh!” he jokes. But the distance was worth it because that church was where his life was slowly transformed.

Alister shares a key moment in his journey: “There was a time in church when I went down to the front to receive prayer. And when I was being prayed for, God began to tell me, ‘Alister, you have to love yourself.’

“When I heard that, tears began to roll down my eyes.”

God began to bring verses like Genesis 1:27 and Psalm 139:14 to Alister’s mind. Alister explains it as God granting him eyes to see what was happening when he was being created.

“I saw how He started to form my body, that I am His workmanship. His eyes, when He looked at me, I was made with love.” That’s a fundamental truth of the Christian faith, but it was one Alister needed God to personally reaffirm.

Hearing God speak gently to him, Alister became convinced of God’s love: “My response to God was: ‘God, help me to start loving myself. Not just my spirit, not just my soul, but help me to love my body because You created me in Your image.’”

LOOKING UP FROM THE LIMITATIONS

Alister knew the first step to renewing his mind was to be mindful of the words he says to himself, so he began to watch out for negative thoughts towards his body.

He elaborates: “For example, if I want to use my hands to reach for something, but my hands cannot stretch far enough to reach it, or if I do not have the strength to even pick it up, I need to watch myself and stop telling myself that my hand is useless.

“I need to tell myself that I’m still loved by God no matter what. That my body is still precious to God.”

Through this conscious decision to be more aware of his thoughts about himself, Alister realised just how many negative thoughts flew through his mind in a day.

Through this conscious decision to be more aware of his thoughts about himself, Alister realised just how many negative thoughts flew through his mind in a day.

“Some of these thoughts are very subtle, but at the first instance when I know these thoughts are not good or edifying, I quickly take hold of them and shut them down instead of letting them fester. Because we become who we believe we are.”

However, the process of learning how to love himself is a difficult journey. Alister shares that the discouragement and past hurts still surface from time to time, but he is beginning to find security in his identity in Christ.

“I learnt not to focus on my weaknesses or limitations because I do have strengths, gifts and talents that God has given to me.”

“We live in a performance-based culture and this makes me feel that my value is affected because I cannot be perfect,” Alister says. “But we are all not perfect. Every one of us has different forms of weaknesses, just that my weakness is more visible than others.

“So I learnt not to focus on the weaknesses or the limitations that I have in my life because I do have strengths, I do have gifts, I do have talents that God has given to me.

“And having weaknesses doesn’t decrease my value. It doesn’t mean that I’m not precious anymore to God.”

In fact, Alister began to ask God what He’d want to say to him every day. The answer? Most of the time it’s three simple words: I love you.

WHY DOESN’T A LOVING GOD HEAL ME?

But if God truly loves Alister, why doesn’t He heal him?

I asked Alister if he’s ever thought about that question. From his reply, it’s clear that this is an issue he has wrestled God with.

“I was once on a mission trip when my leader told all of us to prepare a testimony to share. If we had a healing testimony, we should prepare it too.

“I was thinking: ‘Oh my gosh, if I share my testimony will the people kena (get) stumbled or not?” Alister laughs.

He goes on to explain: “When God heals someone, people will say that God is good. But what if God doesn’t heal or if the healing hasn’t come yet? Will they say that God is not good? I don’t want that to happen when I tell my testimony because I know that God is good.”

Alister shared this conundrum with his leader who, in turn, told him a story.

A professor was talking to his students about the benefits of Lasik surgery. At the end of the presentation, a student asked: “You talked about Lasik, but why are you wearing spectacles?”

The professor replied: “At the start of my presentation, I said that there are many ways to correct eyesight. One of the ways is Lasik. Another way is to wear spectacles.”

That was when Alister realised that God’s goodness can be demonstrated in many ways.

“God’s goodness can come through the form of healing, but it can also be seen when His grace is sufficient for my situation.”

“That’s when I understood that people can’t say that God is not good just because I’m not healed. Because God is good; His goodness is being shown in another way.”

“God’s goodness can come through the form of healing, but it can also be seen when His grace is sufficient for my situation.”

That doesn’t mean Alister does not want to be healed. “I want to be healed,” he says. “And I believe that God is a healer and He is a good Father. But my focus is not on healing as much as it is about how He wants me to live my life.”

Referencing Daniel 3:17 and Romans 8:28, Alister affirms: “The God I serve is able to deliver me, but even if he does not, I still choose to trust in Him because I know that all these things work together for my own good.

“At the end of the day, I’m more impacted when God reminds me that I’m fearfully and wonderfully made,” he concludes. “And God is more concerned about my character than my comfort.”

As I end the interview with Alister, I find myself thinking back to the article that my friend sent me.

I was struck by how the people in the article “accept” their disabilities. One saw it as so closely intertwined with her identity that she wanted her disability to be carried over in the afterlife.

The idea of acceptance looks different for Alister though. He sees his disability as a sign of brokenness in this world and desires to be restored, yet he is able to accept if physical healing never comes in his lifetime.

“God is able to deliver me, but even if he does not, I still choose to trust in Him…”

The key, Alister tells me, is to fully come to terms with the present situation no matter how difficult it is.

“Certain foundations have to be laid. The first: I acknowledge that I have a disability,” he states. “So of course I want to be healed.”

“The second: My self-worth does not come from how the world sees me or how I see myself – it comes from how God sees me.”

Embracing these two realities, Alister is free to pursue healing while the disappointment that comes with the waiting process is mitigated. He can be at peace, no matter the circumstance.

Today, Alister is an associate in Singtel’s Group sustainability department. He gives motivational speeches to students and raises awareness amongst corporations as to how they can better support people with disabilities.

Alister also frequently travels to neighbouring countries to share his life story to encourage youths in similar situations that there can still be meaning and purpose in their lives despite the challenges.

He may have disabilities, but he certainly doesn’t think of himself any less. I think that is self-love and self-acceptance done right.